Some dreams are merely similar, yet there are shared dreams—dreams that are eerily identical.

In 2017, “On Body and Soul”—a film that made waves at the Berlin Film Festival—opens with a scene of a pair of deer entwined together, leisurely foraging in a picturesque snow-covered forest.

Shortly thereafter, the film transitions to a harsh and pungent slaughterhouse, where we meet the two main characters: Mária, a rigid and shy new product inspector, and Endre, the financial manager of the slaughterhouse with a paralyzed arm, a weathered face, and a hardened soul after an unhappy marriage.

There would be nothing remarkable about the deer in the snowy forest if it weren’t for the fact that it is the story of the nightly shared dream between Mária and Endre. Not just similar dreams, but identical down to the smallest detail, complete with mutual interaction.

The main characters in the film “On Body and Soul”. (Photo: Mécs & Mesterházy)

In Endre’s dream, he is a male deer fumbling for a thick leaf, sharing this rare food with a female deer, and then they both go down to the stream to drink water. On the other side, Mária, in her dream, is the female deer who receives the leaf, nudging her companion while drinking water by the stream.

The precise matching details in the dream lead the psychologist character to initially think that Mária and Endre had orchestrated a prank. “What a strange coincidence,” the doctor comments, temporarily believing that the two are not playing tricks.

Thousands of “shared dreams” have been recorded!

The concept of “shared dreams,” as seen in the case of Mária and Endre, is not merely a fabrication by Ildikó Enyedi, the renowned Hungarian director and screenwriter. It is indeed a strange coincidence, though rare, that exists in real life.

According to Dr. Patrick McNamara, a neurology professor at Boston University School of Medicine (USA) who has spent years researching human dreams, there are currently thousands of records documenting cases of shared dreams.

He also categorizes shared dreams into three groups: those between therapist and client, those between close relationships like parents and children, spouses, or twins, and those between strangers.

Dr. McNamara argues that while the phenomenon of shared dreams is widely documented, most of it exists in the form of “anecdotal reports”—that is, recorded accounts rather than data controlled by scientific methods. Particularly in cases where individuals know each other, when one person recounts a recent dream, the other tends to jump in to “complete” the story and “believe” they had the same dream. However, upon closer examination of each detail, differences often emerge.

For the first two groups, the fact that individuals with relationships have similar dreams is relatively easy to explain. According to common scientific perspectives on sleep, dreams are stories created by the brain during the REM (rapid eye movement) phase of sleep.

The materials for these stories come from each individual’s emotions and life experiences. Those in relationships often share common environments and circumstances, making it easier to have similar raw materials to “cook up” similar dreams.

The materials for creating stories come from each individual’s emotions and life experiences.

Conversely, the third group—completely unfamiliar individuals (like Mária and Endre)—is rarely documented, as they have little chance to meet, share, and discover this coincidence.

The source of documentation in this case, which Dr. McNamara confidently refers to, is in Frank Seafield’s book titled “The Literature and Curiosities of Dreams.” Dr. McNamara objectively acknowledges that shared dreams among strangers “can occur,” but he himself has not found a reason why.

According to McNamara, among completely unfamiliar individuals, the only explanation for shared dreaming is that they must be in a completely similar brain state to produce the same cognitive content.

However, this seems unlikely to happen, even among identical twins. He proposes an alternative explanation, which he admits is still unconvincing: that dreams are not simply products of the brain recording and processing information while we sleep.

Dreams may be products of the interactive cultural world of humans, floating in the very “cultural morphospace”, waiting to manifest in individual consciousness.

This second explanation by Dr. McNamara seems to resonate with a theory by a psychologist nearly two centuries ago: the theory of the “collective unconscious” by Carl Jung.

Decoding “shared dreams” through the “collective unconscious”

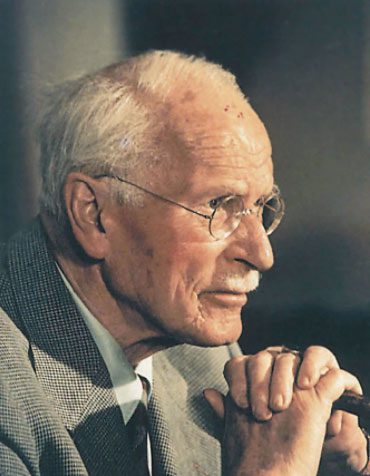

Carl Jung (1875-1961). (Photo: Pinterest)

Carl Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist and psychologist, was a student of the father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, and one of the pioneers laying the groundwork for this field of study.

He believed that dreams are the mind’s effort to communicate with the individual, and that when two different people share the same dream, they are drawing data from a common source known as the “collective unconscious.”

“Collective unconscious” is a concept that puts Carl Jung at odds with Sigmund Freud’s view, as he argued that the “unconscious” is not formed solely from personal experiences.

According to Jung, the “collective unconscious”, sometimes referred to as “objective subconscious,” is the deepest part of the human subconscious, built from collective experiences: ancestral experiences passed down through genetic material.

As described by Carl Jung, the “collective unconscious” is created from instincts and archetypes—these exist in the form of primal images or symbols, which can overlap and combine, yet are suppressed by consciousness. Some archetypes proposed by Jung include the mother, birth, death, and rebirth…

Among these, the archetype of the “mother” is the most significant, which can take the form of the Virgin Mary, Mother Earth, forests, oceans…

Thanks to the concept of the “collective unconscious,” the similarities and universality of human behaviors or behavioral inclinations, such as innate fears, justice, or righteousness, can be more easily explained as inherited traits. Those who share the same dream may do so because they share these fundamental primal archetypes.

Carl Jung believed that dreams provide us with insights into the “collective unconscious.” He suggested that symbolic objects and signs have universal meanings in dreams, as they represent archetypes.

In other words, similar symbols in dreams carry similar meanings, even among different individuals.

He also believed that dreams serve as a compensation for the repressed parts of consciousness in daily life. This lays the scientific foundation for dream research, serving as a tool for investigation, analysis, and treatment of psychological conditions or phobias.

Nevertheless, the theory of the “collective unconscious” also faces debate and criticism as a “pseudoscientific” theory, as it is challenging to prove with data or images that archetypal symbols are inherited and available at birth.

Thousands of people have been recorded to have identical dreams: Perhaps you have also ‘participated’

Returning to the case of Mária and Endre, if Carl Jung’s reasoning is correct, then the dream of the pair of deer in the snow-covered forest is a beautiful symbol of two lonely and harmonious souls yearning for love, fortuitously and fortunately finding each other in real life.

At the very least, audiences watching the film in many countries around the world can use the metaphorical symbols in their dreams to decode this poetic film, despite the lack of scientific evidence.

And who knows, each of us may have already or will “share a dream” with someone—if Carl Jung’s hypothesis is universal?