The disease known as encephalitis lethargica or Economo disease (also referred to as sleeping sickness) – where individuals afflicted by this condition desire to sleep constantly and often do not awaken or become incapacitated – has been documented since the 17th century and remains one of the strangest and most enigmatic diseases yet to be unraveled.

Appearance

The sleeping sickness was first observed in the 17th century when several individuals in London (England) suddenly fell into a prolonged state of drowsiness with symptoms resembling encephalitis, failing to awaken for weeks, and not consuming food or drink. Efforts to rouse them through noise, light, and various other means were futile. This disease was first described in 1917 by Austrian psychiatrist and neurologist Konstantin von Economo, who named it “encephalitis lethargica” (hence it is sometimes referred to as Economo’s disease).

The initial symptoms typically appear quite suddenly, beginning with headaches and fatigue, followed by a state of stupor, sometimes accompanied by delirium, although the patients can be easily awakened. The disease can lead to early death or persist for several weeks or even months. What is frightening is that this illness does not present uniform symptoms – it is akin to a multi-faceted form of chickenpox, manifesting in various ways.

Over the centuries and up to the present, the origins and treatment methods for encephalitis lethargica remain a significant challenge for scientists. (Source: russian7.ru).

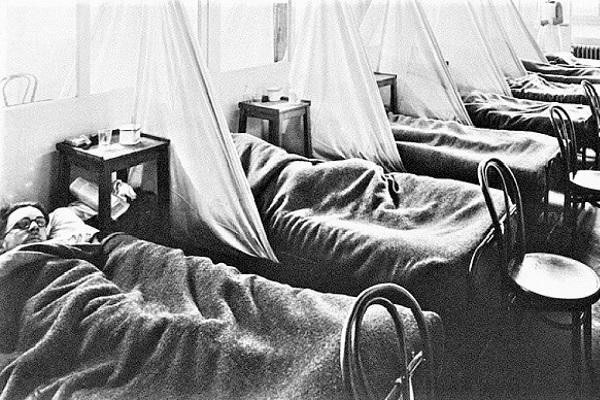

One-third of patients with sleeping sickness die during the acute phase, falling into a coma that cannot be awakened or entering a state of severe insomnia where they cannot be made to sleep, often resulting in death within 10 to 14 days. Due to difficulty breathing while asleep, patients often adopt unusual postures. Sometimes insomnia is accompanied by persistent high excitement, driving patients into a state of frenzy, both physically and mentally.

These patients remain in a state of agitation and constant movement until death, completely exhausted within a week or 10 days. The total number of estimated victims is around 1.6 million (some sources indicate 5 million, with the epidemic lasting 10 years), and approximately 20% of survivors require lifelong professional care; fewer than one-third of patients fully recover.

Encephalitis lethargica did not re-emerge for over two centuries – until the winter of 1916-1917, when residents in Vienna (Austria) and other European cities suddenly began to feel drowsy. One of the first recorded cases was near Verdun in France, where the disease struck and claimed the lives of several soldiers. During the pandemic, everyone was diagnosed with sleeping sickness, as prolonged sleep leading to death was the only sign of the illness.

However, at that time, everything was thought to be due to the overload and chronic fatigue of soldiers. Doctors at times speculated that the cause of their unusual symptoms was mustard gas, widely used in warfare. But when civilians began to fall ill, doctors had to concede that it was not due to toxic gas. The disease spread rapidly across the globe alongside the Spanish flu, which claimed 50 million lives, causing it to receive less attention.

Sleeping Sickness in the Soviet Union

From Europe, encephalitis lethargica spread to Ukraine and Russia of the Soviet Union. In Nizhny Novgorod, the first case was recorded in March 1921, and within the next three years, 18 men and 13 women in this territory fell ill. In Moscow, the first carriers of the disease appeared in September 1922, and two months later, there was a sudden spike in patients with strange symptoms – lethargy, difficulty breathing, eyelid paralysis, and fever, making it very hard to awaken them; they would doze off even while eating.

Doctors noted that in patients, the paralysis spread to the eye muscles, causing drooping eyelids, and in some cases, it developed into strabismus; it was impossible to identify which social class was at risk of the disease, and the incidence rate – everyone, regardless of age, gender, or social status, was affected. As sleeping sickness is transmitted through small droplets in the air, it was believed that the causative agent was an unidentified virus. There were speculations that the outbreak was related to the aftermath of the Spanish flu that ravaged in 1918-1919.

Either Europeans weakened by the flu became “easy prey” for the new virus, or encephalitis became a late complication of the Spanish flu. According to Professor Mikhail Margulis from the Department of Neurology at Moscow University, in early 1923, the number of cases in the Soviet capital was around 100, with the highest incidence occurring in January. He described the symptoms of sleeping sickness: patients fell into a prolonged sleep, yet remained partially conscious.

This sleep could last from one week to one month, depending on the complexity of the disease form and the characteristics of the individual’s immune system. Among the patients diagnosed with this condition at the Старо-Екатерининская Hospital, one in four died. Those who recovered found it impossible to return to their normal lives, remaining paralyzed or demented; the least harmful complication following the illness was strabismus.

The sleeping epidemic in the Soviet Union became a genuine emergency, leading to the establishment of a committee to study Economo’s disease. Rich clinical observations became the basis for the monographs of N. Chetverikov, A. Grinshtein, as well as published medical collections. These experts noted an increase in the incidence of sleeping sickness among the Jewish population, as well as a correlation of this disease with trauma and other illnesses.

However, Soviet medicine could not outline an effective treatment method, while the West was also mired in speculation. Soviet doctors focused on boosting immunity, improving overall diet, reasonable physical activity, and free medical care, including annual health check-ups. To protect themselves from infection, Margulis recommended implementing “precautionary measures similar to those for other infectious diseases.”

Sleeping sickness spread globally, and by 1927, 5 million people fell ill due to lethargy, but in all countries, the epidemic disappeared as abruptly and mysteriously as it had erupted. Today, Economo’s encephalitis is referred to as a “rare clinical disease,” and it has never returned on a massive scale. The last major outbreak was recorded in the territory of the former Soviet Union – in 2014, 33 residents of the Akmola region of Kazakhstan were infected.

Over the past centuries, the most advanced laboratories and leading scientists have attempted to explain the phenomenon of encephalitis lethargica and develop a treatment method, but the “sleep virus” – the causative agent of the encephalitis lethargica epidemic has yet to be isolated, and the disease remains one of the greatest mysteries in history.