The tooth embedded in the skull of a creature with saber-like teeth reveals new information about an ancient ritualistic battle.

The conflict among gorgonopsians, a group of carnivorous saber-toothed animals from the late Permian period (299 – 251 million years ago), may have been for dominance, mates, or territory rather than lethal intent. Researchers discovered this after analyzing a healed bite mark on a gorgonopsian skull found near Cape Town, South Africa, as reported by Live Science on November 10.

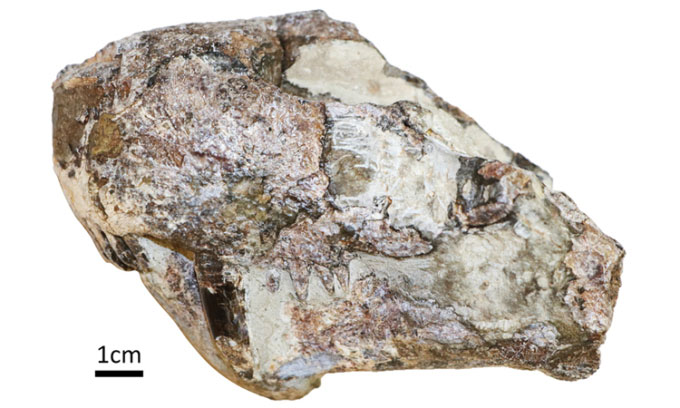

Gorgonopsian skull from the middle Permian period. (Photo: Julien Benoit)

The bite mark on the animal’s snout still contained a tooth embedded inside. This is the first time scientists have observed such a wound in gorgonopsians. The name gorgonopsian is derived from the Gorgon monster in Greek mythology.

Paleontologist Lieuwe Dirk Boonstra discovered the skull and lower jaw of a gorgonopsian in the Karoo region, a semi-arid area of South Africa, in 1940. However, it wasn’t until this year that researchers identified the bite mark. They noted that the skull had healed after the severe bite, indicating that the animal did not die immediately from this injury.

Based on the healing rate of injuries in mammals, the research team determined that the wounded gorgonopsian lived for an additional 2 to 9 weeks. There were no signs of infection, suggesting that the bite was not the ultimate cause of the animal’s death.

Gorgonopsians varied in size from that of a cat to a hippopotamus. The skull specimen used in the new study is not from the late Permian period but from the middle period, meaning it predates the time when gorgonopsians became dominant predators, according to Julien Benoit, a paleontologist at the Evolutionary Studies Institute of the University of Witwatersrand.

During this time, anteosaurs, a group of short-legged carnivores with large canines, were thriving on Earth. The gorgonopsian that the research team studied was relatively large among the world of these colossal monsters. Anteosaurs had large teeth capable of easily crushing a gorgonopsian’s skull, leading researchers to conclude that they were not the culprits.

“This leads us to hypothesize that a gorgonopsian bit it, not to kill but to assert dominance in a ritualistic battle,” Benoit stated.

Illustration of a gorgonopsian biting another of its kind. (Photo: Morgan Hopf)

Today, adult reptiles and mammals, especially carnivores, use biting behavior to assert dominance, promote mating and ovulation, and compete for mates, territory, and reproductive rights.

“Unlike the bite of a predator aimed at killing its prey, biting the face without causing death is a common outcome of such ritualistic battles. For us, this indicates that the perpetrator was another gorgonopsian of the same species. This conclusion also aligns with the size of the tooth,” Benoit explained.

Gorgonopsians are the first recorded saber-toothed predators. However, the broken tooth embedded in the skull is not a saber tooth but could be a canine, incisor, or post-canine tooth. This new finding suggests that complex behaviors such as biting existed not only in mammals and dinosaurs but appeared earlier and were more widespread than previously thought.