After participating in activities that generate significant emissions, billionaires like Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos are heavily investing in climate change mitigation projects to offset their carbon footprint.

The scenario of billionaires enthusiastically promoting potential solutions to combat climate change while simultaneously flying around the globe, leaving behind a substantial carbon footprint, occurs frequently. Just in the past week, this situation happened twice.

Bill Gates’ yacht Lana anchored off Buyuk Boncuklu Bay, Mugla Province, Turkey, on October 27. (Photo: Ali Riza Akkir/Anadolu Agency)

First was Bill Gates, who is openly supportive of the fight against climate change. Gates celebrated his 66th birthday by hosting dozens of guests, including Jeff Bezos, on a superyacht in the Mediterranean, near the Turkish coast. Some guests arrived at the yacht via helicopter. A few days later, Bezos also faced backlash for using his private jet to attend the COP26 climate summit in Scotland.

The ultra-wealthy often argue that their fame and busy schedules require them to travel by private jet, helicopter, or yacht. In his book “How to Avoid a Climate Disaster”, published in 2021, Gates stated that he offsets his emissions (excluding aviation) by “purchasing carbon offsets through a company that operates a facility to remove CO2 from the air.” On November 2, a spokesperson for Bezos’ $10 billion Earth Fund announced that Jeff Bezos also “offsets all of his carbon emissions from his flights.”

Bill Gates at COP26 in Glasgow, Scotland, on November 2. (Photo: Evan Vucci/Pool/Reuters)

Carbon offsets are not tools exclusive to billionaires. Anyone can invest in carbon offsets. So, what exactly are these tools?

Theoretically, carbon offsets allow an entity to compensate for its carbon emissions by funding environmental projects that reduce greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. One carbon offset credit is said to equal one ton of CO2, or an equivalent amount of other greenhouse gases, removed from the air.

A drive from San Francisco to Atlanta, approximately 4,000 km, produces about one ton of CO2, according to estimates from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). An average car emits about 5 tons of CO2 each year.

Companies or governments can purchase carbon offsets to compensate for emissions produced during manufacturing. Meanwhile, individuals typically use them to offset emissions from driving or flying. Credits can be purchased from companies and tree-planting programs or by funding renewable energy projects, and even from farmers who reduce or sequester methane emissions from livestock.

Theoretically, an average driver could offset their vehicle’s carbon emissions for less than $100 per year. According to a study by Bank of America in September, the cost of carbon offsets typically ranges from $2 to $20 per ton of emissions removed.

Bill Gates spends about $5 million each year to offset his family’s carbon emissions. He does not specify exactly where this money goes but has invested in several carbon offset companies, including the Canadian startup Carbon Engineering and the Icelandic company Carbfix. Carbon Engineering uses a “direct air capture” process to extract CO2 from the air and store it safely. Meanwhile, Carbfix captures CO2 from power plants and stores it in volcanic rock.

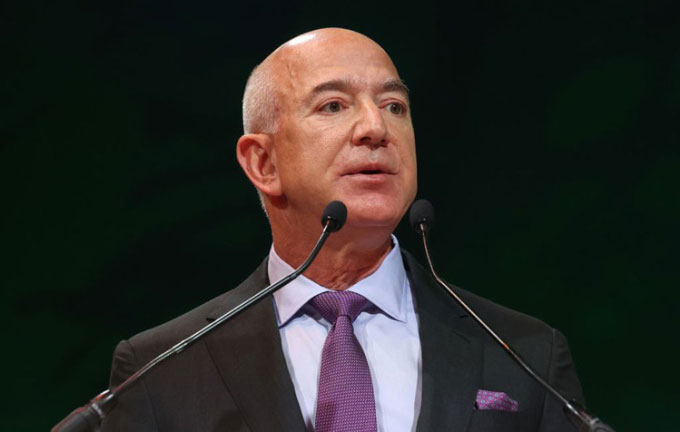

Jeff Bezos speaking at COP26 in Glasgow, Scotland. (Photo: Chris Jackson)

The actual effectiveness of carbon offsets remains a topic of debate. According to a 2019 report by ProPublica, many programs selling carbon credits for carbon reduction projects later failed to implement those projects.

California is making efforts to offset its carbon emissions by heavily investing in forests, aiming for carbon neutrality by 2045. However, a study by the nonprofit CarbonPlan in April revealed that California has overestimated the climate value of its efforts, and the offsets do not reflect the actual climate benefits.

Last month, environmental organization Greenpeace called for an end to carbon offsets, citing concerns from some experts that carbon offsetting is diverting funding away from long-term climate solutions. Others argue that carbon offsets are merely a convenient way for billionaires and corporations to justify their polluting activities rather than genuinely reducing emissions.

Nevertheless, carbon offsets seem to be growing in popularity, especially as governments and organizations commit to significantly reducing emissions. Global spending on carbon offsets could rise from around $300 million in 2018 to $100 billion by 2030, according to the Institute of International Finance (IIF).

A common rationale is that purchasing carbon offsets is still better than doing nothing. Many companies and individuals are entirely capable of—and should—make improvements to reduce their carbon emissions, but it can be challenging to reduce them to zero.

This appears to be Bill Gates’ strategy as well—reduce emissions when possible, purchase carbon offsets to compensate when not. He even suggests buying more than necessary to ensure accuracy: “Since the method of calculating carbon emissions is still rudimentary, I doubled my family’s carbon footprint to ensure we offset all that we produce.” Gates shared.