During our school years, we have likely heard the name Gauss at least once, often accompanied by anecdotes or theorems left by this mathematical prodigy. Indeed, it is widely believed that if we exclude the name Newton, few mathematicians have had as significant an impact on modern mathematics as Carl Friedrich Gauss. His name is placed alongside other eminent mathematicians such as Euler and Archimedes. Some say that had Gauss published all his research, mathematics might have advanced 50 years earlier than it did. Like Newton, Gauss’s brilliance was not confined to mathematics alone; he also made substantial contributions to fields such as geodesy, astronomy, physics, electrostatics, and optics.

“Learn to calculate before learning to speak”

Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss (April 30, 1777 – February 23, 1855).

His full name is Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss, born on April 30, 1777, and passing away on February 23, 1855. Gauss is celebrated as the “Prince of Mathematicians,” a title that stems not only from his contributions to mathematics but also from his extraordinary ability to calculate from a young age. Gauss’s family belonged to the working poor in German society, and his mother was illiterate with little knowledge. Due to her illiteracy, she could not record Gauss’s birth date precisely, only recalling that he was born in April, 8 days before Ascension Day and 39 days after Easter. As a child, using the information his mother provided, Gauss was able to calculate his own birth date and discover various methods to determine dates on the calendar.

Many anecdotes recount that Gauss exhibited remarkable calculation skills by the age of 3, an age when most children are still crying over lollipops. One day, he happened to see his father calculating sales records and noticed a small error, which he pointed out to his father. The father was skeptical, thinking how could a 3-year-old know right from wrong, but he checked and recalculated nonetheless. To his surprise, he indeed had made a mistake right where Gauss indicated.

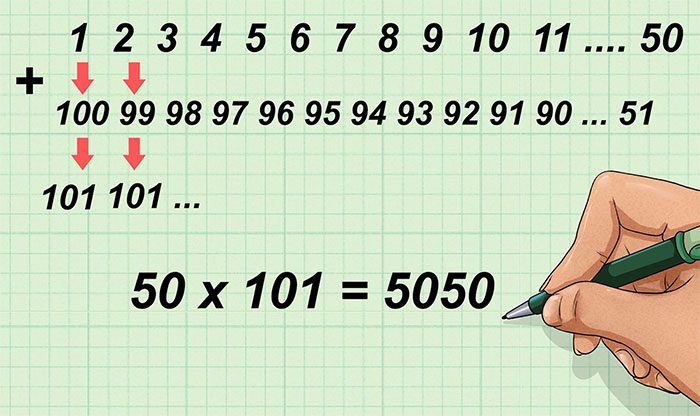

When Gauss was 7, another anecdote emerged showcasing his calculating prowess. In school, the teacher presented a problem: find the sum of the numbers from 1 to 100. This seems like a straightforward arithmetic series today, but for a 7-year-old, it was quite complex. After thinking for a few seconds, Gauss claimed to have solved it, but the teacher doubted he could do it so quickly and asked him to check again, suggesting he might have made a mistake. However, Gauss was correct, and he presented a remarkably clever and simple solution that astonished both the teacher and his classmates. His method was as follows:

- Gauss noticed that if you sum the pairs of numbers from the start and end of the series, they always yield the same total. For example, 100 + 1, 99 + 2, 98 + 3, etc., all equal 101. There are 100 numbers, which means there are 50 pairs summing to 101, so he simply multiplied 101 by 50, yielding 5050. Extremely quick and efficient. Historians believe this is a true story, although some details may vary from reality.

Impressed by Gauss’s exceptional intellect, Duke Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand granted him a scholarship to attend the Collegium Carolinum secondary school. Gauss later studied at the University of Göttingen. During his studies, he continuously discovered many important mathematical theorems, such as proving that all regular polygons can be constructed with a compass and straightedge provided the number of sides is a Fermat prime. Fermat primes have the form 2^(2^n) + 1, examples being 3, 5, 17, 257, etc. Speaking of construction with compass and straightedge, there is a fascinating story about Gauss.

A 19-Year-Old Student Successfully Solves a 2000-Year-Old Problem

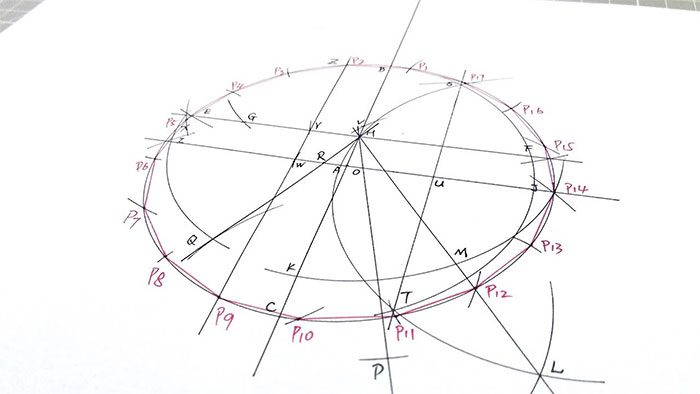

About 300 years before Christ, mathematicians from the time of Euclid struggled to solve a seemingly simple problem that no one had ever addressed comprehensively: how to construct regular polygons using only a compass and a straightedge. At that time, people had only found methods to construct squares, equilateral triangles, and regular pentagons, and by Gauss’s time, only up to 15-sided polygons.

Returning to Gauss, now a young man just under 19, still in college. Every day, his instructor would assign him two problems to work on as homework. As usual, these problems were not challenging enough to occupy Gauss for long, and he would solve them in just a few hours. However, one day, Gauss accidentally found an additional problem mixed in with his assignments. He was surprised to see three problems assigned that day, but he set to work on it without complaint. The problem read: “Using a compass and an unmarked straightedge, construct a shape with exactly 17 equal sides.”

Clearly, this was a case of a problem that had existed for over 2000 years and had never been solved in a general way, particularly for the case of 17 sides. This problem was much more complex than the previous two. Gauss spent a considerable amount of time, every hour ticking away through the night, applying all his knowledge and intellect to find a way to construct the shape. He toiled with pencil, paper, compass, and straightedge until morning, and it seemed he had finally solved the problem.

Even though he had solved it, Gauss still felt embarrassed, thinking he had taken too long. He approached his instructor and said, “I apologize for the time it took me to solve this; I spent the whole night on the third problem…” The teacher was astonished by his words, quickly took Gauss’s paper to review, and stood frozen in shock. The teacher asked:

Did you really solve this?

Yes, of course, but it took me all night to finish it. I’m really incompetent – Gauss replied.

The teacher urged Gauss to sit down and asked him to draw a regular 17-sided polygon in his presence. Gauss drew it to the teacher’s amazement, and upon completion, the teacher exclaimed: “Do you realize this is a problem that has never been solved by anyone before, not even Archimedes or Isaac Newton? This problem has existed for over 2000 years, and you solved it in one night; you are truly a genius!”

Many believe that the problem was intentionally given by the teacher to challenge Gauss, while others think that the teacher himself was puzzled by the difficult problem and inadvertently included it in Gauss’s assignment. Regardless, that moment marked a significant milestone in mathematical history.

Gauss was taken aback by the teacher’s remarks, transitioning from disappointment to joy and happiness. The regular 17-sided polygon and its construction became one of the works Gauss cherished most in his life. He even requested that upon his death, this shape be inscribed on his tombstone. Interestingly, constructing this shape on stone proved too difficult, so the stone carver declined Gauss’s request, leaving his wish unfulfilled.

Gauss’s current tombstone.

Later, Gauss reflected, saying, “If anyone had told me that this was a difficult problem with a 2000-year history that no one had solved, I probably would have given up and not been able to complete it.” This statement serves as a lesson: perhaps if we are unaware of how challenging the problem we face is, we may perform better than if we are constantly reminded of the potential difficulties.

Research Above All

Gauss has numerous famous and significant contributions to science, but in this article, I prefer to share intriguing anecdotes rather than delve deeply into specialized knowledge. He was always a perfectionist in his work, prioritizing research above all, even family. It is said that when Gauss was engaged in research and received news that his wife was nearing death from a messenger, he replied: “Tell her to wait for me a moment so I can finish my work.”

Gauss was a very individualistic person who liked to chart his own course.

Gauss was also a very individualistic person who preferred to determine his own path. Despite extensive research, he rarely published his works for the world to see. This was not because he wanted to keep this knowledge to himself, but rather because he fundamentally believed that his research was not yet complete or perfect. This behavior is quite similar to how he felt guilty for spending an entire night finishing a homework assignment from his teacher, as mentioned earlier. He always adhered to the principle of pauca sed matura, which means “few but ripe.” Due to his infrequent publications, there are many instances where mathematicians discovered works published independently by others that had actually appeared in Gauss’s notes decades earlier. A notable example is the discovery of non-Euclidean geometry, which Gauss had explored but chose not to publish, leading to its later attribution to Janos Bolyai. This illustrates that he was a mind ahead of his time, which is why he is so deeply respected by posterity.

There is also an amusing anecdote involving Gauss and Bolyai. Janos Bolyai’s father, Farkas Bolyai, was a friend of Gauss and had attempted to explore Euclidean geometry based on its axioms but was unsuccessful. When Janos Bolyai published his findings on non-Euclidean geometry, Gauss wrote to Farkas, stating, “To praise this work would be like praising myself, as it aligns with what I have thought and researched for over 30 years.” This statement created tension in the relationship between Gauss and the Bolyai family.

The Fields Medal’s Twitter page also posts congratulations and commemorations on Gauss’s birthday each year.

Contemporaries also described Gauss as extremely strict and conservative. He rarely collaborated with others on research and often isolated himself from the crowd. During the event when mathematicians raced to solve Fermat’s Last Theorem, Gauss stood on the sidelines and declined to participate. The rare occasion he did collaborate was with Wilhelm Weber, resulting in significant contributions to the field of magnetism (which is covered in university-level physics courses).

Later Life

For his contributions, Gauss was honored worldwide, especially in his homeland of Germany. From 1989 to 2001, Germany featured his image and the Gaussian distribution he discovered on the 10-mark banknote. Additionally, the country issued commemorative stamps for the 100th and 200th anniversaries of his birth. A long-time student of his wrote extensively about him, viewing him as a giant in the field of science.

From 1989 to 2001, Germany featured him on the 10-mark banknote.

Thanks to his contributions to astronomy, his name was given to a crater on the Moon and the asteroid 1001 Gaussia. Gauss passed away on February 23, 1855, due to a heart attack. Upon his burial, his genius brain was preserved for study, in hopes of uncovering the secrets behind his extraordinary intelligence.