Scientists have successfully read the contents of a 300-year-old handwritten letter without opening it. The technique they used promises to unlock historical “treasures” sealed within ancient letters while preserving the integrity of the documents.

The letter was written on July 31, 1697, by Jacques Sennacques. In the letter, Sennacques simply asks his cousin, Pierre Le Pers—a French merchant living in The Hague—for a certified copy of the death certificate of Daniel Le Pers.

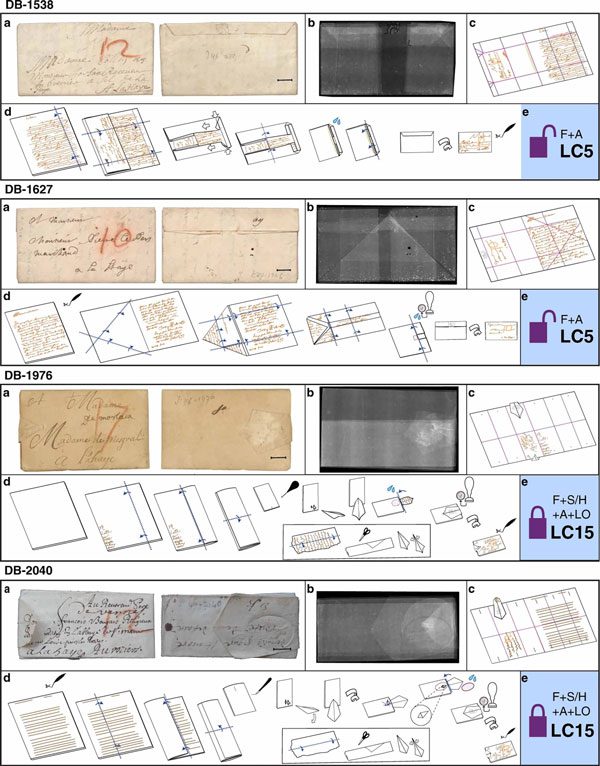

Sennacques’ letter was wrapped using a technique known as “letterlocking”—a complex folding method that seals the letter with wax. This technique was used worldwide to secure letters before the invention of envelopes. It functions like an ancient security method; the letter cannot be opened without tearing it. If a tear occurs, it indicates that the letter has been opened and its contents could have been altered or forged before reaching the recipient.

A type of letterlocking used in England in 1587.

Jana Dambrogio, one of the authors of the research published in the journal Nature Communications, stated: “Letterlocking was a daily activity that took place for centuries across many cultures, borders, and social classes.”

The “letterlocking” technique has persisted for centuries and played a crucial role in the history of security techniques. It first appeared in letters stored in the Secret Archives at the Vatican from 1494. While researchers could open the letters to read their contents, they aimed to preserve all the folds.

Although this distinctive technique was gradually replaced in the 1830s with the advent of mass-produced envelopes, it has recently inspired new ideas among scholars.

They faced a challenge: How can you read the contents of such letters without permanently damaging these invaluable historical pieces?

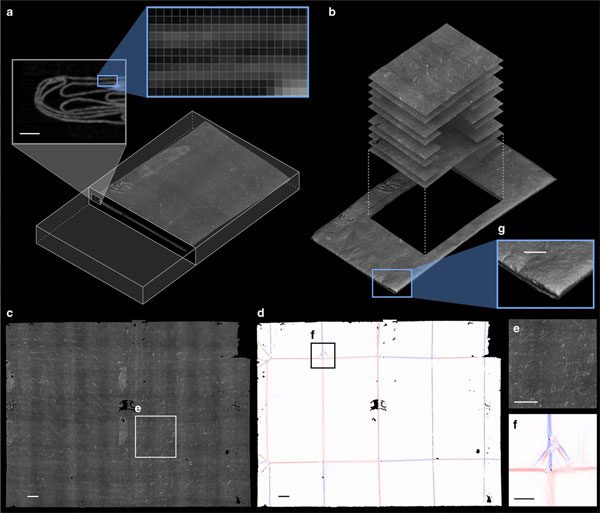

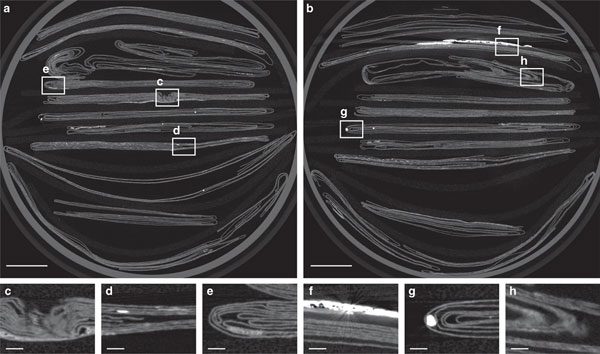

Researchers from MIT and King’s College London used a dental X-ray machine to create high-resolution 3D scans, accurately showing how the paper was folded. They then employed an algorithm to generate readable images of the letter’s content and folds. According to the research team, virtually opening the letter using techniques like CT scanning allows for a 3D reconstruction of the letter and using algorithms to recreate a 2D version of the letter, presenting it in a flat state, including images of both sides and the folds.

Computer algorithms have been successfully used to reconstruct and read the contents of documents and scrolls with one or two folds. However, the complexity of the letterlocking technique poses challenges for these algorithms.

For instance, the handwritten letter from Jacques Sennacques is part of the Brienne Collection, a wooden chest belonging to a curator in Europe containing 3,148 items, including 577 unopened letters. The research team has managed to open several of these letters using new techniques and believes that this can be applied to many other types of letters. For example, there are unopened items among the 160,000 letters currently held at Prize Papers—the repository of documents seized by the British from enemy ships between the 17th and 19th centuries. Before the aid of machinery and algorithms, researchers could only discern the names of the recipients written on the outside of the letters.

This new letter unlocking technique opens a new door for a wide range of research across various scientific fields, including history, postal security, sociology, and finance, particularly enabling researchers to access a vast reservoir of untapped materials from archival centers around the world.