The Mu Variant that once raised concerns due to its potential vaccine resistance has not been detected anywhere in the world for over a month.

In September, news of a new Covid-19 variant named Mu, or B.1.621, which was believed to have the ability to evade immunity, shocked the world.

Scientists hold models illustrating various Covid-19 virus variants. (Photo: Getty Images).

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the Covid-19 advisor to U.S. President Joe Biden, told reporters at the time: “This variant carries a number of mutations that suggest it will evade certain antibodies, not just monoclonal antibodies, but also antibodies in serum and vaccines.” However, Dr. Fauci also noted: “There is not a lot of clinical data on this, mostly lab data.”

At that time, the scenario of a vaccine-resistant variant caused waves of fear across the globe. The Delta Variant was known to have a higher vaccine resistance compared to the original SARS-CoV-2 virus. Could the Mu variant, first detected in Colombia, be even worse than Delta? Mu has specific mutations associated with immune resistance, as well as a mutation called P681H that is linked to increased transmission rates.

However, nearly a month later – shortly after the World Health Organization (WHO) classified Mu as a “variant of interest” – data from the outbreak tracking website outbreak.info indicated that the Mu variant has not been detected in the U.S. or anywhere else in the world since September 21, 2021.

Is Mu Still a Threat?

Does this mean that Mu is no longer a threat? The short answer is: possibly. However, Joseph Fauver, a scientist at Yale School of Public Health, would not go so far as to say it has been “wiped out” as some reports have suggested.

“To say it has been ‘wiped out’ implies that we, as humanity, have tried to make that happen. The reality is that Mu has been outcompeted by the Delta variant,” Fauver explained.

A similar trend was observed with the Alpha variant, or B.1.1.7, first detected in the UK. According to outbreak.info (a public health database on Covid-19 that collects genomic data from the GISAID initiative), the Alpha variant was last detected in the U.S. on September 17, 2021, and globally on September 21, 2021.

Healthcare workers administer the Covid-19 vaccine to the elderly in the U.S. (Photo: AP).

As Fauver explained, the times mentioned are the last detection of the gene for each variant in random samples from Covid-19 patients. Since not all infections are sampled and tested for DNA, there is no way to be absolutely certain whether the variants still exist, especially when the rate of positive Covid-19 cases remains high.

However, in reality, weeks have passed, and the Delta variant continues to dominate globally.

From one perspective, Delta’s dominance over other strains may be fortunate. Delta spreads 50% faster than Alpha and is 50% more transmissible than previous variants. However, the Mu variant certainly possesses a concerning array of mutations of its own.

Dr. Fauver stated: “The Mu variant contains a concerning set of mutations. The mutations in it, particularly in the spike protein and receptor-binding domain, appear to evade the immune system more than some other ‘variants of interest.’ If it weren’t for the dominance of the Delta variant, it could be a greater concern and may have reached a much higher [infection] frequency.”

If So, Why Is the Delta Variant Winning?

Scientist Fauver explained: “I can confidently say that the Delta variant is more transmissible, but the exact reason why is still unanswered, and the scientific community has a lot of work to do.” He speculated that Delta’s success might relate to something happening at the molecular level.

If variants that once ravaged the early stages of the pandemic are essentially gone, and Delta is the dominant variant globally, does that mean the Delta variant could persist long-term?

Currently, scientists are unsure about this. RNA viruses like SARS-CoV-2 are constantly mutating. Although technically, the old virus variant no longer exists, their nature is to mutate and evolve as they infect host cells and replicate.

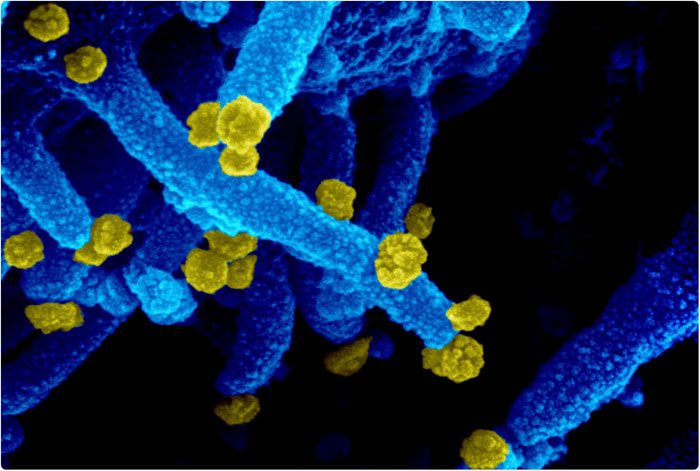

Magnified images in experiments neutralizing the Mu variant with convalescent serum and vaccines. (Photo: Getty Images)

In fact, the Delta variant has also mutated, though it is not yet clear to humans. Generally, the mutation rate depends on the virus.

Sasan Amini, founder and CEO of Clear Labs, a private gene company, stated: “Viruses replicate, survive, and pass on their genes to the next generation by making more copies of themselves. This replication process is not perfect, meaning that while duplicating, errors will also be introduced. But these errors are often corrected, and the result of that actually produces nearly identical copies.”

According to Amini, many mutations are eliminated through natural selection, but sometimes mutations create a competitive advantage, as seen with the Delta variant.

“Those mutants replicate faster, are more transmissible, and ultimately become a more dominant force over time,” Amini said.

This expert noted that some mutations of Delta are similar to Mu, but not all.

This suggests that the Delta variant could mutate into something else altogether.

This also means that an even worse resurgence of the Delta variant could be on the horizon.

Dr. Fauver mentioned that he does not work in the “prediction business,” but believes that many mutations found in the “variants of interest” are shared because they have a common “menu.” “Are there new mutations waiting to be discovered that could make the virus even more dangerous? I don’t know. But the Delta variant is a really bad virus, and I hope it doesn’t get worse than this,” Fauver said.