In the 1880s, Josephine Garis Cochran revolutionized the way people washed dishes by inventing the first modern dishwasher. Unlike earlier devices, Cochran’s invention cleaned dishes using water pressure, providing greater efficiency and paving the way for a new era in household appliances.

Josephine Garis Cochran may be a name that few recognize, but her invention in the 1880s forever changed the dishwashing process and laid the groundwork for the modern home appliance industry. Not only was she a talented inventor, but Cochran also demonstrated her business acumen, manufacturing, and marketing skills, allowing her to overcome challenges and establish a lasting legacy.

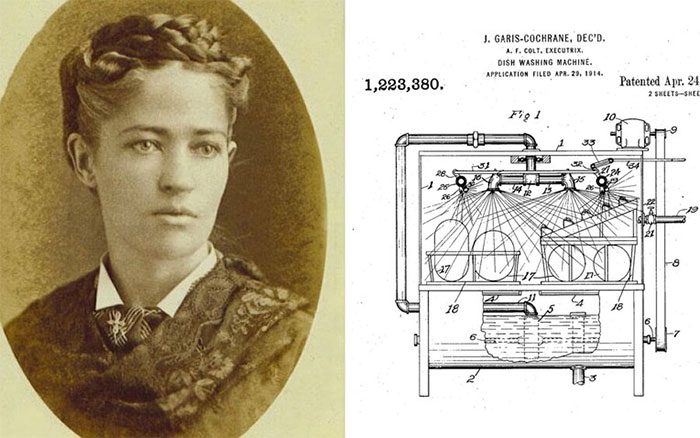

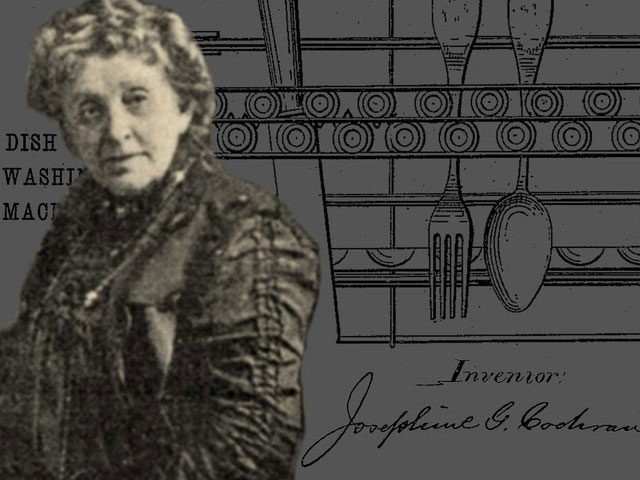

Josephine Garis Cochran and her dishwasher design.

Born around 1839 – 1841 in Ashtabula County, Ohio, Josephine Garis grew up in a family with a tradition in engineering. Her father was a civil engineer who worked with complex machinery in factories and pumping systems. This family background likely had a significant impact on Cochran, even though she had no formal training in mechanics.

She married William Apperson Cochran in 1858, and together they settled in Shelbyville, Illinois, leading a quiet family life. However, the sudden death of her husband in 1883 left her with significant debt. To overcome her difficulties and find a way to support herself, Cochran began thinking about creating a machine that could alleviate the burdens of household chores – the dishwasher.

Cochran wanted to create a machine that used powerful water pressure to blast away dirt.

At that time, washing dishes was a time-consuming and labor-intensive job, especially for affluent families with many fine china dishes. Cochran noticed that earlier dishwasher designs relied on scrubbing mechanisms with brushes, making them ineffective for thorough cleaning. However, Cochran’s idea was different: instead of using brushes, she aimed to create a machine that used powerful water pressure to blast away dirt and debris stuck to the dishes.

Without formal academic knowledge in engineering, Cochran sought help from a mechanic named George Butters. Together, they researched and built the first machine, a simple yet effective brass device. She designed separate racks for each item to avoid chipping and breaking during the washing process. In 1886, Cochran officially received a patent for her invention from the United States Patent and Trademark Office, marking the birth of the first dishwasher.

Her product was inaccessible to many families due to its high cost.

After obtaining the patent, Cochran set about manufacturing and selling dishwashers. However, the market was not yet familiar with this novel device, and the high cost (up to several hundred dollars at the time) made her product inaccessible to many families. Most average households lacked a hot water system, a necessary condition for operating Cochran’s dishwasher. For wealthy families, her product was merely a luxury. Consequently, Cochran focused on selling her product to businesses such as hotels and restaurants, where there was a high demand for efficiency and time-saving in cleaning tasks.

To ensure quality and avoid dependency on other manufacturers, Cochran decided to open her own production factory, with George Butters as the manager. At this factory, she faced many technical challenges and even encountered disrespect from male employees. In a 1912 interview with the Chicago Record-Herald, Cochran shared that the staff often did not follow her instructions because they believed she lacked mechanical knowledge. It took a great deal of time and effort for Cochran to prove that her design and methods were correct, leading to more effective dishwasher operation.

Cochran decided to open her own manufacturing plant to avoid dependency on others.

Cochran was not just an inventor; she was also a talented marketer. In interviews, she often described herself as a wealthy woman who invented the dishwasher out of frustration with numerous servants chipping her fine china. However, census records indicated that she did not actually have many servants, and the story of her affluent background might have been a marketing strategy to create appeal for her product. Cochran also encouraged the press to believe she was the granddaughter of John Fitch, the inventor of the steamboat. Despite knowing this information was inaccurate, she maintained this impression to enhance her credibility and public interest.

Cochran continuously improved the design and functions of the dishwasher.

Despite the embellished stories in her marketing campaigns, Cochran remained a skilled and persistent woman. She did not stop at invention; she actively participated in manufacturing, sales, and overseeing the installation process. Cochran continuously improved the design and functions of the dishwasher, consistently registering patents for new enhancements that increased the product’s effectiveness and quality.

In 1890, Cochran moved to Chicago and introduced the dishwasher at the Columbian World Expo in 1893. This event marked a new chapter for her as she won an award for her invention. Cochran continued to promote and showcase the dishwasher at major fairs in Massachusetts, New York, and Missouri, where her product attracted the attention of both businesspeople and the public.

After Cochran passed away in 1913 in Chicago, her company was transferred and later merged into the KitchenAid brand, marking a new phase of development for dishwashers. It wasn’t until the 1950s and 1960s, when hot water systems became more common, that dishwashers truly became popular household appliances.