Galileo Galilei was a renowned scientist of ancient times, born in Pisa, Italy. Throughout his life, he pursued truth, dedicated himself to science, and bravely upheld his principles.

Galileo Galilei (1564 – 1642): He was an Italian astronomer and physicist. Coming from a poor family, he did not complete his university education but taught himself and, by the age of 25, was invited to become a university professor. He was the first to introduce the principle of inertia, the concepts of force and acceleration, paving the way for classical mechanics and experimental physics. He was also the first to use a telescope to observe celestial bodies, proving and developing Copernicus’s theory that the sun is the center of the universe.

Galileo Galilei.

He is posthumously hailed as the “Father of Modern Science.”

During his school years, Galileo was a curious student who often posed questions and sought to prove interesting problems on his own. One of his teachers posed a challenging question to the students: Using a piece of string to form various closed shapes, which shape has the largest area? To find the answer, Galileo experimented with shapes like squares, rectangles, and circles, eventually discovering that the circle has the largest area among the shapes. He even applied his mathematical knowledge to prove this claim.

His teacher was delighted with Galileo’s proof and encouraged him to continue studying mathematics.

Galileo grew increasingly interested in mathematics, often reading books by famous scientists, particularly enjoying the works of the Greek philosopher Aristotle. He also loved to discuss and explore the content of these books. Gradually, he realized that many of Aristotle’s ideas lacked rigorous dialectical thinking and were based merely on intuition and experience.

Aristotle believed that if two objects were dropped simultaneously from a height, the heavier one would fall first, while the lighter one would follow. Galileo began to doubt this, thinking: “If two balls fall from above, large and small, don’t they hit the ground at the same time? Is Aristotle wrong, or am I?”

Later, Galileo became a mathematics professor at the University of Pisa and expressed his skepticism about Aristotle’s theories.

His colleagues were buzzing with discussions about his doubts; some claimed that Aristotle was such a great figure that his views could not possibly be wrong.

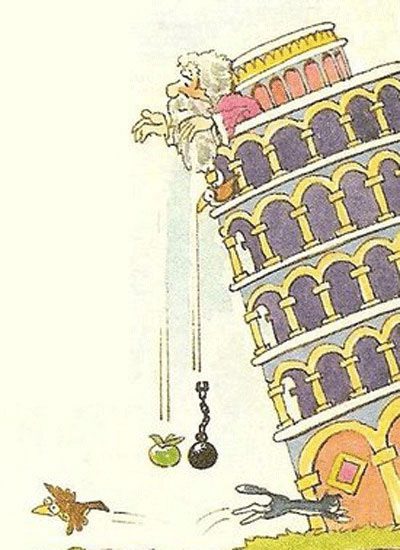

Some thought he was trying to be controversial. Others remarked that the Church and the Pope acknowledged Aristotle’s teachings as truth, and Galileo dared to question this truth. It was madness. However, Galileo disregarded the gossip and sought to use experimentation to validate his ideas. He recalled his childhood days climbing the Pisa Tower with his siblings, throwing stones of different sizes, and observing that they all hit the ground simultaneously. Thus, he decided to climb the Pisa Tower to conduct an experiment for everyone to witness.

Galileo advertised in the city, writing: “Tomorrow at noon, everyone is invited to the Leaning Tower of Pisa to witness a falling objects experiment.” The news spread, and the next day, a large crowd gathered to watch the experiment, including scientists, ordinary townsfolk, friends, and even his detractors. Some laughed at him, claiming that only a fool would believe that a feather and a stone would fall to the ground at the same time. At that moment, Galileo felt confident because he and his students had conducted the experiment multiple times, each time proving it correct.

The experiment commenced, and Galileo and his students placed two distinctly sized iron balls into a box with a removable bottom. By pulling the bottom away, both balls would fall freely at the same time. They raised the box to the top of the tower, and everyone below watched intently. Galileo personally pulled the bottom of the box, and all eyes were on the two iron balls, one large and one small, as they fell.

With a “thud,” both balls hit the ground simultaneously, prompting the spectators to cheer, while Galileo’s critics fell silent. The reality everyone witnessed confirmed:

All objects falling from a height do so in the same time, regardless of weight.

Notably, in 1969, astronauts landed on the moon and conducted an experiment, dropping a feather and a rock simultaneously. The result showed that both the feather and the rock fell to the moon’s surface at the same time. This demonstrated that without the resistance of air, a feather and a rock would fall to the ground simultaneously.

The famous story of the experiment at the Leaning Tower of Pisa continues to resonate around the world today, becoming a historical scientific anecdote.

The Story of the Telescope

One summer, Galileo received a letter from a friend mentioning: “A Dutchman has invented a very special telescope. Yesterday, while walking along the riverbank, I met him. Across the river, there was a beautiful girl, and through the lens, I could see her face as if she were standing right in front of me. I was so amazed that I thought I could reach out and touch her, but when I did, I almost fell into the river; she was still far away on the other side! Unfortunately, he didn’t have any more telescopes to sell to you.”

Galileo read the letter repeatedly, jumping with joy, exclaiming: “I must create such a telescope! I want to see the faces of distant people, and perhaps even the stars up in the sky!”

To create this special telescope, Galileo sought out related materials and began to experiment. He sketched on paper while calculating with a tool. After a night of effort, he finally found a method to make the telescope. Wanting to create this device, he needed to buy several lens blanks for testing, but finding no money in his pockets, he told the servant: “Take my coat and pawn it for cash!” The servant, unwilling to do that, took her own money to buy the lens blanks.

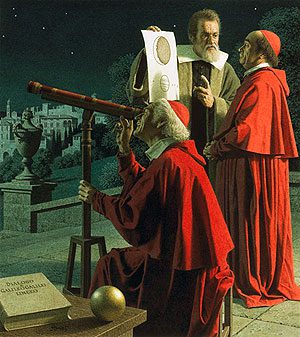

Once he had the materials, he began grinding the lenses. Galileo was well-versed in the properties of lenses, but grinding them was labor-intensive. It took him several days to grind two lenses, one convex and one concave. He used two tubes, one large and one small, that could fit into each other, attaching the lenses to the ends of these tubes. The only task left was to adjust the distance between the two lenses to bring distant objects closer and magnify them. Galileo lifted the simple yet extraordinary tube to observe a tree outside his window, adjusting the distance between the two lenses until, at the optimal position, he suddenly saw the tree appear distinctly, as if he could reach out and touch it. Galileo had succeeded in creating a telescope that could see far away, and he was overjoyed! He was determined to continue improving the telescope for greater distances. Thus, he began designing, calculating, sketching, and grinding lenses… After a summer of effort, the magnification of the lens increased from 3 to 9 times. Later, he managed to create a telescope that could magnify objects up to 33 times, which came to be known as the “telescope.” Because it truly functioned as a telescope, it has retained that name to this day.

After successfully producing the telescope, news spread quickly throughout Europe, and many people were eager to buy his telescopes. Since the most crucial part of the telescope is the lens, Galileo spent day and night grinding lenses. Despite this, he still could not produce enough to meet the demand.

Galileo continued to manufacture and improve telescopes while also using them to observe the sky, laying the groundwork for his future studies in astronomy.

The Truth Shines

In the vast sky, countless stars shine, distant and mysterious. In Galileo’s time, people believed that all the stars were fixed and that the Earth was at the center of the universe. This was known as the “Geocentric Theory,” which everyone accepted at the time. However, Galileo used his telescope to observe celestial bodies in motion. He wrote in his book: “Nothing is static; the sun rotates, and the Earth rotates as well. The Earth not only revolves around the sun but also spins on its own axis.”

The doctrine of Galileo, upon its inception, offended the Church, which categorized his theory as “The Sun-Centered Universe Theory”, viewing it as heretical. The Church was unwilling to accept any theories that diverged from tradition, insisting that the Earth remained the center of the universe. The Church’s religious court summoned Galileo, who received a warning from the Pope, prohibiting him from promoting the “Sun-Centered Universe Theory” in any form.

Despite the backlash against him, Galileo remained committed to his research. It took him six years to complete his book, which discussed two viewpoints: “The Sun-Centered Universe Theory” and “The Earth-Centered Universe Theory.” This book propagated new ideas, was written vividly and humorously, and upon its publication, it sold out quickly.

Those opposing Galileo attacked him after reading his book, claiming that its publication violated the ban and exacerbated the situation.

Thus, just six months after its release, the book was banned. The Pope believed the disparaging remarks about Galileo from a few narrow-minded individuals, and the Roman Curia and the Kingdom of Spain collaborated to issue a warning, a severe measure at that time.

Two months later, the Roman court summoned Galileo to the tribunal. Despite being 69 years old and bedridden due to illness, he was still escorted to Rome.

Initially, the Church sought to have Galileo admit that his promotion of the “Sun-Centered Universe Theory” was erroneous and required him to write a declaration ensuring he would not promote it again. However, Galileo refused to admit guilt or write such a declaration, stating: “What I wrote in my book is objective; I do not oppose the Pope. What crime have I committed? Should I hide the truth and deceive people? Am I to be punished for speaking the truth?”

The interrogation lasted five months, and Galileo’s health deteriorated, yet he showed no remorse for his actions during the proceedings. Due to his weak condition, he had to be carried back on a stretcher after each session. The Church court, recognizing his critical health situation, ruled: “Galileo’s crime is contradicting the doctrine and promoting heretical theories, punishable by life imprisonment.”

After the court’s ruling, Galileo was imprisoned near Rome, losing his freedom. Nevertheless, at night, he continued to write until his eyesight failed him. He believed that the light of truth would ultimately triumph over all dark forces. Not long after, Galileo took his last breath.

More than 300 years later, in 1979, the Roman Curia publicly exonerated Galileo. The Pope officially declared that the judgment against Galileo was a serious mistake. History finally rendered a fair and just verdict for this great scientist, and Galileo’s name will forever be respected by humanity.

“I believe there is nothing more painful in this world than the absence of knowledge.”

— Galileo —