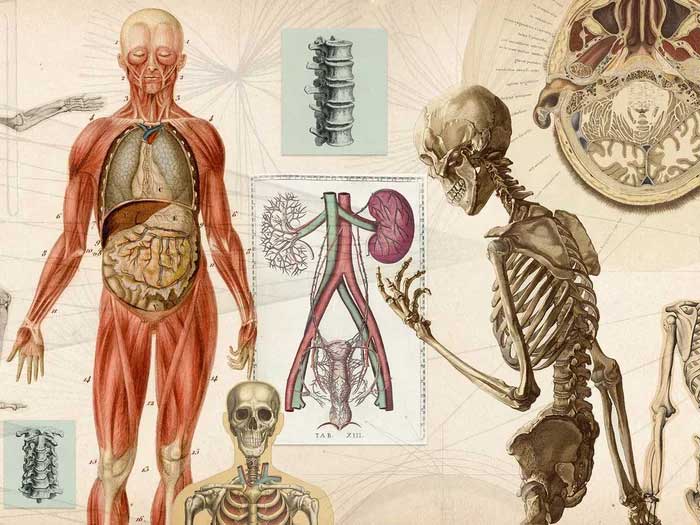

In nature, animals exhibit two common forms of skeletons: those with hard exoskeletons, like many mollusks, and those with internal skeletons, like humans and other vertebrates. In the latter case, the main component of their bones is calcium phosphate, more specifically hydroxyapatite.

Regardless of the type of skeleton an animal uses for survival, the primary material it employs is calcium.

This raises the question: why did animals evolve to choose calcium over other metals?

As we know, the calcium content in the Earth’s crust is not the most abundant metallic element; aluminum and iron are more prevalent, and calcium is not the only metallic material utilized by the human body—our bodies are filled with various metals.

However, all animal species have chosen calcium as the material for their defensive and structural body components.

Our bodies are filled with various metals.

1. Calcium Strengthens Bones but Isn’t the Best Choice

Many might think that our bones are fragile and hope that advanced science will create a steel skeleton to enhance durability.

In reality, calcium compounds like bone and hydroxyapatite have a tensile strength of 150 MPa (pressure measurement unit in the International System, where 1 Pa = 1 N/m²), a strain at failure of 2%, and a fracture strength of 4 MPa(m).

About 35% of human bone is organic matter, while the remaining 65% consists of calcium phosphate and a very small amount of calcium carbonate. These substances determine the strength of bones.

If hydroxyapatite were as dense as steel, it would be much stronger than steel; calculations suggest that the strength of human bone is five times that of steel.

The reason bones break lies in the fact that bones are not entirely solid; they comprise tubular and hollow structures.

Bones consist of tubular and hollow structures.

This structure withstands pressure better while remaining lightweight. In fact, our bones account for only about 1/6 of our body weight, making running more energy-efficient than if we had solid bones.

Studies have shown that the activation energy for the iron oxidation-reduction reaction is similar to the ATP energy needed for the body to produce hydroxyapatite. However, if the body were to construct a skeleton from steel and exist in a form similar to hydroxyapatite, it could be 3 to 5 times heavier than the current skeleton, leading to significant disadvantages for daily activities.

Overall, it is challenging to find excellent materials for bone construction like calcium compounds in nature, but based on our current technology and among commercially produced materials, bone is certainly not the best option for the body.

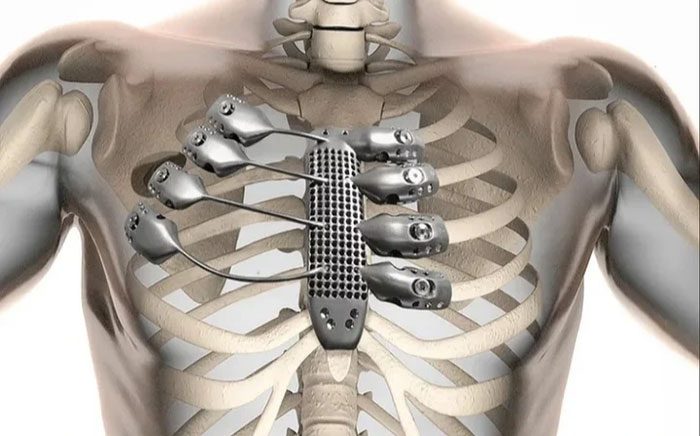

Among those, titanium alloys can achieve similar weight and volume to bone but with superior parameters. For instance, the stress of titanium alloys is 1.3 times greater than that of bone of the same weight, and their strength is five times that of bone.

The most crucial aspect is that the tensile strength of titanium alloys reaches 500 MPa. If we had a titanium alloy skeletal frame, we could support a heavier and larger body, essentially eliminating the need for cells to repair bones.

Additionally, carbon fiber, which is widely used in prosthetics and other fields to help reshape the human body, has also proven to yield better results than existing bone.

2. Why Do Most Organisms Choose Calcium?

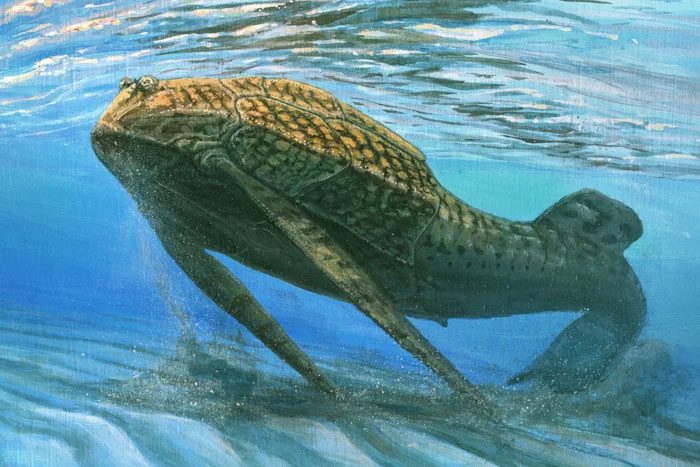

Approximately 635 to 485 million years ago, a series of chemical changes occurred in the oceans, including a shift in the composition of oceanic rocks from dolomite to limestone, coinciding with the emergence of animal bones.

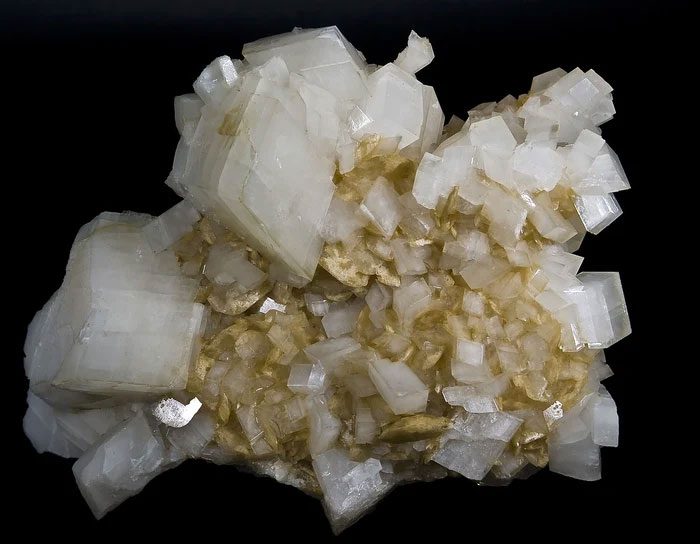

Notably, the increase in limestone correlates closely with the appearance of animal bones over time. Researchers also discovered that aragonite and calcite crystals found in limestone form more quickly and require less energy than dolomite.

In other words, if an organism were to use dolomite to create calcium-containing bones, it would expend significantly more energy.

Dolomite forms under low oxygen concentrations in the ocean, and researchers believe that the sudden rise in limestone content was due to the oxidation of rocks as Earth’s oxygen levels increased during that period.

Dolomite forms when oxygen levels in the ocean are low. (Illustrative image).

A similar chemical process occurred on land—perhaps even more intensely than in the oceans—and then, under the influence of rain, large amounts of limestone dissolved and flowed into the ocean, making calcium ions one of the most abundant ions in the ocean (following sodium and magnesium among metal ions), facilitating the evolutionary process of bones.

Biological evolution prefers to utilize readily available materials; it takes a long time to identify the most suitable materials for survival and then optimize their use.

In general, there are two crucial considerations when selecting biological materials: one is how much energy is wasted in using this material, and the other is the abundance of this material and the convenience of extracting it. Thus, the abundant calcium in the ocean has become a suitable material for the evolution of animals.

The abundant calcium in the ocean has become a suitable material for the evolution of animals.

Typically, titanium alloys are very durable and lightweight, making them excellent materials for bone construction. Furthermore, titanium is also quite abundant in the Earth’s crust, but it primarily exists in the form of water-insoluble titanium dioxide. Therefore, it is a challenging material to utilize.

Another energy-related factor is that many oxidation reactions of calcium compounds are energy-releasing processes, and animals can also derive energy when extracting calcium compounds.

For this reason, some researchers even believe that the initial reason animals developed calcium-containing bones might be due to calcium waste products generated during metabolism that were ultimately repurposed as bone.

While organisms on Earth utilize carbon effectively, it is challenging to obtain carbon fibers through biological processes; moreover, carbon fibers require immense amounts of energy and extremely high temperatures.

There is another critical reason why animals do not construct their bodies from titanium alloys and carbon fibers: calcium phosphate and calcium carbonate are both poorly soluble in water.

The importance of water for life is not only that it participates in certain chemical reactions, but water itself serves as a solvent carrier for life substances; all chemicals involved in life activities must be dissolved in water to complete their processes.

When the human body floats in the womb, the developing body begins to form, and the seeds that will eventually form bones—cartilage—begin to appear. Cartilage is a type of tissue that is not as rigid as bone but is more elastic and, in some respects, serves more functions.

Later in the development of the fetus in the womb, a significant amount of cartilage begins to transform into bone—a process known as ossification. When ossification occurs, the cartilage begins to calcify.

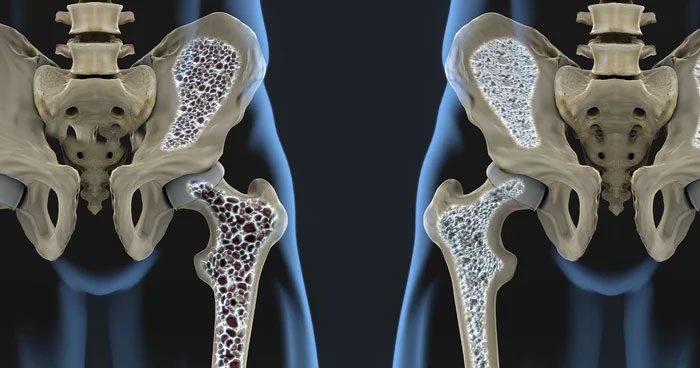

The primary component of vertebrate bones is calcium phosphate, not calcium carbonate, because the solubility of calcium phosphate in water is 1.5 times that of calcium carbonate.

The solubility of calcium carbonate in pure water is 14 mg/L, while that of calcium phosphate is 20 mg/L. This also means that bones made from calcium phosphate will develop approximately 1.5 times more efficiently than those made from calcium carbonate.

Because materials such as aluminum, iron, titanium, and carbon fibers are insoluble in water, cells cannot use them as building materials for the internal skeletons of vertebrates.