During high school, all of us had to solve spatial geometry problems at some point. And once you start solving spatial geometry problems, you’ve likely encountered this scenario: while drawing a figure, you run out of paper.

All such cases are related to a “deformed triangle”, with two unusually long sides, so that no matter how much you draw, they never intersect within the bounds of the paper. In this situation, how would you solve it?

Illustrative image.

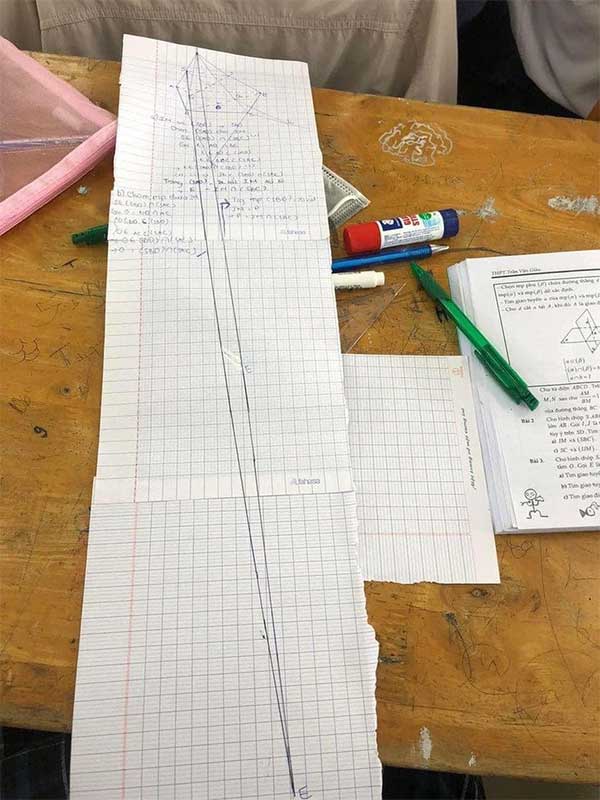

Some very creative students might continue their drawing in another dimension, that is, on the back of the paper. Others will take another piece of paper and place it under the old one to complete the drawing. Or, if the situation is urgent, you might even draw the triangle spilling out onto the desk.

However, some might argue: Why insist on finishing that “deformed triangle”? Just draw until the paper runs out and stop there. In fact, if you don’t complete the drawing on the paper, your solution is definitely incorrect.

But a new study published in the American Mathematical Monthly will make them reconsider. Sometimes, the part of the triangle that extends beyond the paper may contain unexpected mathematical mysteries.

Specifically, in this case, with a “deformed triangle,” two high school students in the U.S. discovered a way to prove the Pythagorean theorem that was considered “impossible” for over 2,500 years, since it was first stated.

Illustrative image.

No one has ever proven the Pythagorean theorem this way, not even Albert Einstein

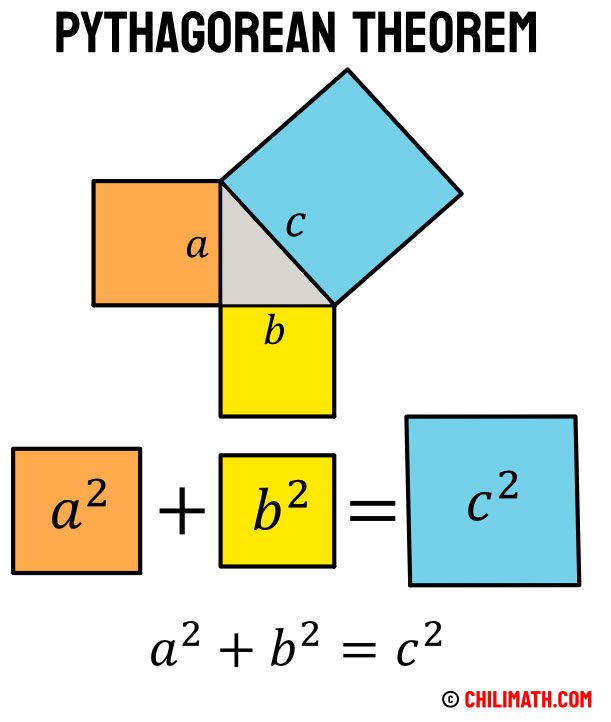

The Pythagorean theorem is named after the ancient Greek mathematician Pythagoras (570-495 BC) – the first person to prove it, although there is evidence that mathematicians from other ancient civilizations such as Babylon, India, Mesopotamia, and China also independently discovered it:

That in a right triangle, the square of the hypotenuse is always equal to the sum of the squares of the lengths of the other two sides. If a right triangle has lengths of the two legs as a and b, and the hypotenuse as c, then the Pythagorean theorem is expressed by the formula:

𝑐² = 𝑎² + 𝑏²

Without knowing the Pythagorean theorem, ancient Egyptians would not have been able to build pyramids.

It seems like a simple formula, but without the Pythagorean theorem, ancient Egyptians could not have constructed the pyramids, the Babylonians could not have calculated the positions of the stars, and the Chinese could not have divided their land.

This theorem also lays the foundation for many mathematical schools such as spatial geometry, non-Euclidean geometry, and differential geometry – without it, or if it were proven false, nearly all branches of geometry that humanity knows today would collapse.

Proving the Pythagorean theorem is therefore a very important task. Thus, as early as 500 BC, the ancient Greek mathematician Pythagoras undertook this task and made his name known in history.

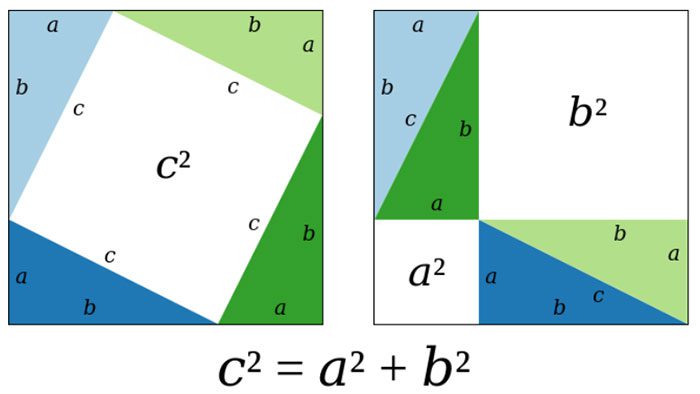

He proved the Pythagorean theorem using a very simple method:

Illustrative image.

He drew a square with a side length of a+b. Then, at each corner, he continued drawing four equal triangles, with sides a and b. These triangles are all right triangles, with the hypotenuse c, creating a white space inside the square with an area of c².

Then, simply by rearranging the positions of those four triangles, Pythagoras created two new white spaces that are squares with sides a and b. The total area of these two white spaces is a² + b², which must equal the original white space c².

This is the proof you would find in seventh-grade math textbooks. But there is another proof of the Pythagorean theorem that you may not have learned. That is the solution proposed by Albert Einstein when he was only 11 years old.

At that time, Einstein realized that if he dropped a perpendicular line AD from the hypotenuse BC of the triangle ABC, he would get two right triangles similar to triangle ABC. Now, just by drawing squares outside triangle ABC with sides equal to each of its sides, Einstein would obtain three squares with areas a², b², and c².

Because the ratio of the area of a right triangle to the area of a square constructed on its hypotenuse is equal for similar triangles, we also get 𝑐² = 𝑎² + 𝑏².

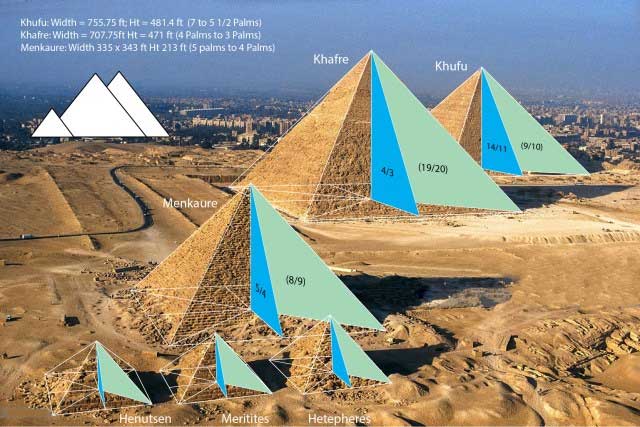

Illustrative image.

However, these are just two of the 370 proofs of the Pythagorean theorem that mathematicians have discovered over the past 2,500 years. From using algebra, calculus to various geometric transformations, this mathematical theorem can be proven true through methods ranging from simple to complex.

Despite this, in all of these proofs, none used trigonometric formulas. Because the Pythagorean theorem itself is a fundamental theorem in trigonometry, proving it using trigonometry would lead us into a logical fallacy trap, called circular reasoning, where we use the Pythagorean theorem to prove the Pythagorean theorem.

Mathematicians have continuously failed in this task, to the extent that in 1927, American mathematician Elisha Loomis exclaimed that: “There cannot be a proof of the Pythagorean theorem using trigonometry because all basic trigonometric formulas must rely on the correctness of the Pythagorean theorem.“

But it turns out, Elisha Loomis was mistaken.

Nearly 100 years later, these two high school students discovered a way to prove the Pythagorean theorem using trigonometry

In a new study published in the American Mathematical Monthly, two students Ne’Kiya Jackson and Calcea Johnson from St. Mary’s Academy in Colorado presented not just one but ten proofs of the Pythagorean theorem using trigonometry.

Ne’Kiya Jackson (left) and Calcea Johnson (right).

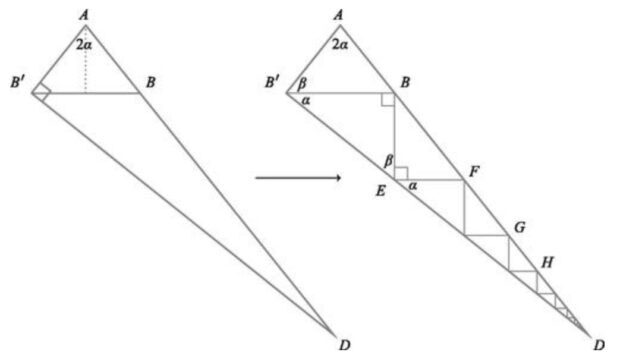

To achieve this, Jackson and Johnson used a right triangle ABC as usual. “Our first proof starts by flipping triangle ABC over its side AC to create an isosceles triangle ABB’,” the duo wrote in their paper.

In the next step, they will construct the right triangle AB’D by extending side AB to point D so that from D, a perpendicular can be dropped to line B’A.

At this step, make sure you have enough paper, as AB’D is a triangle with unusually long sides and point D may very well extend beyond the edge of your paper.

Next, from point B, you will drop a perpendicular to BB’, intersecting B’D at E. Then from E, drop a perpendicular intersecting AD at F… Continuous iterations will yield countless similar triangles whose areas add up to the area of triangle AB’D:

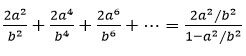

Now for the crucial point:

Jackson and Johnson noted that since BB’ has a length of 2a and triangle B’EB is similar to triangle ABC, they could calculate the length of side BE as 2a²/b. BF=2A²c/b². Similarly, sides FG, GH could be calculated as 2a⁴c/b⁴ and 2a⁶c/b⁶…

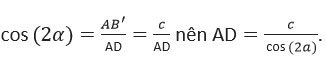

Thus, the length of the hypotenuse AD would equal the sum of the segments:

![]()

In triangle AB’D, we have:

From these two formulas, we can establish the equation:

Where we use the sum of a basic converging series:

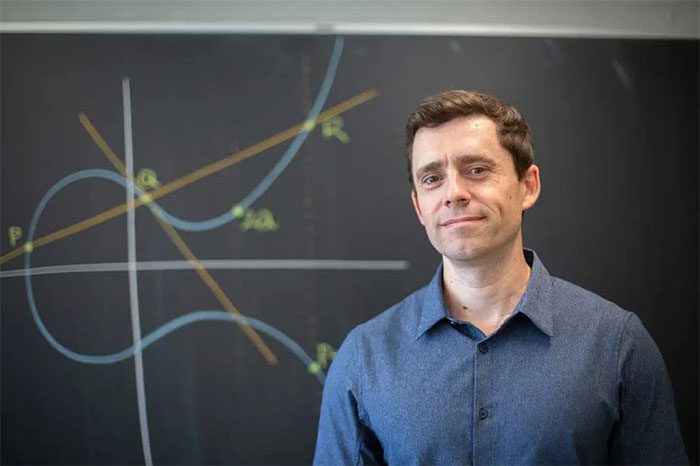

Immediately after its publication, Jackson and Johnson’s proof of the Pythagorean theorem attracted the attention of mathematicians, including Álvaro Lozano-Robledo from the University of Connecticut.

“It looks nothing like anything I have ever seen before“, Lozano-Robledo said. The idea of filling a large triangle with an infinite number of smaller triangles and then calculating its side length using a converging series is an unexpected creativity for high school students.

Mathematician Álvaro Lozano-Robledo from the University of Connecticut praises Ne’Kiya Jackson and Calcea Johnson.

“Some people think that one has to spend years in schools or research institutes to solve a new mathematical problem“, Lozano-Robledo stated. “But this solution has proven that it can be done even while you are still a high school student.“

Not only did they prove the Pythagorean Theorem using a completely new method, but Jackson and Johnson also emphasized a delicate boundary in the concept of trigonometry.

“High school students may not realize that there are actually two versions of trigonometry associated with the same term. In that case, trying to understand trigonometry is like trying to understand a picture with two different images overlapping each other“, they said.

The surprising solution to the Pythagorean Theorem came from Jackson and Johnson’s separation of these two trigonometric variants and their use of another fundamental law of trigonometry, the Law of Sines. By doing so, the duo avoided the circular reasoning that previous mathematicians, including Elisha Loomis, encountered when they attempted to prove the Pythagorean Theorem using the Pythagorean Theorem itself.

No one has ever proven the Pythagorean Theorem this way, not even Albert Einstein.

“Their results have drawn other students’ attention to a fresh and promising perspective“, commented Della Dumbaugh, the editor-in-chief of the American Mathematical Monthly.

“This will also spark many new conversations about mathematics“, Lozano-Robledo said. “This is when other mathematicians can use this paper to generalize that proof, to generalize their ideas, or simply to use that idea in different ways.“

It is evident that a new domain in mathematics has been opened up after Jackson and Johnson sketched out a “mutant triangle“. A triangle extending beyond the edge of the paper contains a loop of infinite triangles.

So next time you are solving geometry problems and encounter the edge of the paper, try drawing it out completely. Who knows, you might just make a new discovery.