Four years after its inception, Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity was validated by a rare astronomical phenomenon, elevating his name to new heights.

In February 1919, two groups of astronomers from the Greenwich and Cambridge observatories set out to Sobral (Brazil) and Príncipe (an island off the West African coast) with advanced equipment to photograph a solar eclipse crossing South America, the Atlantic Ocean, and Africa on May 29.

The expeditions, led by Frank Dyson of the Royal Greenwich Observatory and Arthur Eddington of the University of Cambridge, aimed to test Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity.

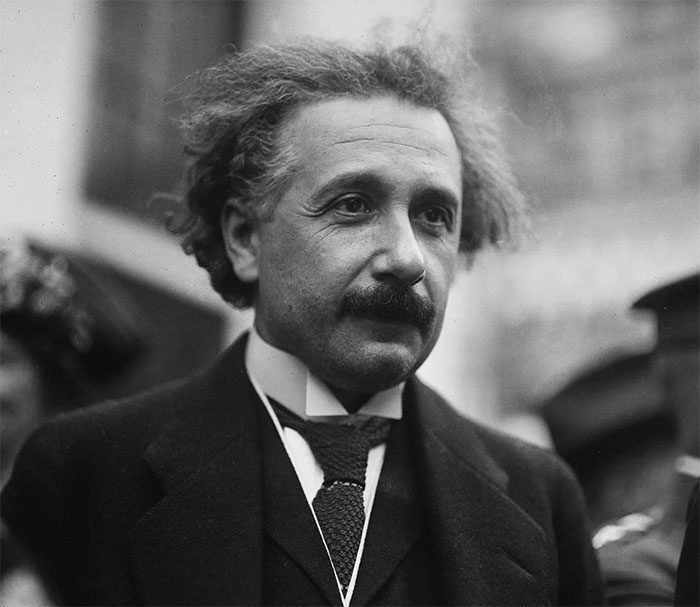

Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity was tested in 1919. (Image: Harris and Ewing Collection/Library of Congress, Washington, D.C).

This renowned theory was published in 1915 but remained met with skepticism from many scientists. The solar eclipse provided a rare opportunity to verify one of the essential consequences of general relativity: the phenomenon of light being bent by gravitational forces.

Einstein’s theory predicted that light rays passing near a massive object in space would be deflected, following the curvature in spacetime created by that object’s mass. In the case of light emitted from a distant star passing close to the edge of the Sun, Einstein calculated a deviation of about 1.75 arc seconds.

Under normal conditions, Einstein’s prediction would be untestable. The simple reason is that sunlight overwhelms the light from nearby stars, rendering them invisible to observers on Earth. However, the shadow of the eclipse would allow astronomers to observe and photograph the star field surrounding the Sun.

By comparing these images with control images taken at night, the degree of light bending of the stars as the Sun appeared could be measured. A favorable factor was the presence of a bright star cluster known as the Hyades near the Sun during the eclipse.

On the day of the eclipse, the team in Príncipe struggled with a cloudy sky, while the team in Brazil had to resort to a lower-quality backup telescope when images from the main telescope became blurred. Nevertheless, both teams ultimately managed to capture images.

After several months of analysis, in November 1919, Eddington and Dyson announced their findings supporting general relativity.

The press reported extensively. The Times of London declared: “A revolution in science. A new theory of the universe. Newton’s ideas have been overturned.” The New York Times headlined “Light Distorted in the Sky.”

This news immediately elevated Einstein, a relatively well-known physicist prior, to a globally renowned figure. Media outlets began to delve deeply into the complex nature of Einstein’s work, emphasizing that only a few people in the world could comprehend it.

According to a commentary from Britannica, the 1919 solar eclipse phenomenon was a landmark event, not only proving general relativity but also affirming Einstein’s genius and extraordinary intellect.