NASA believes that regions with terrain sculpted by ice, water, and dust such as Terra Sirenum on Mars may be concealing life.

A new study published in the scientific journal Nature Communications Earth & Environment suggests that tiny organisms could find suitable shelter just below the surface in certain areas of Mars today.

Lead author Aditya Khuller from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) stated: “If we are trying to find life anywhere in the universe today, then the icy regions on Mars are probably one of the most accessible places.”

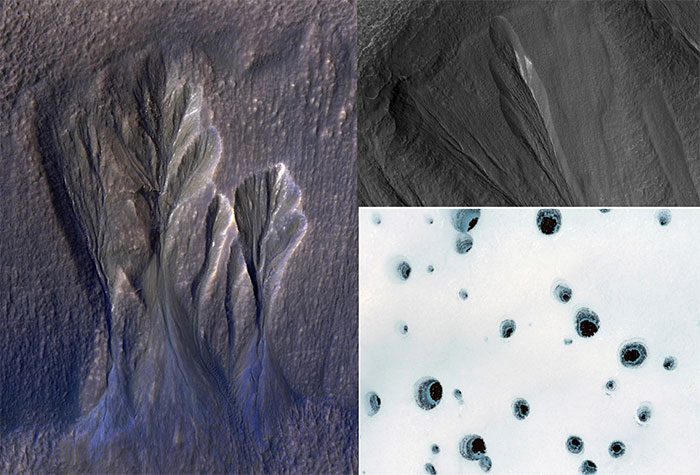

Terra Sirenum (left) and Dao Vallis (upper right) on Mars may host cryoconite holes similar to the icy regions of Alaska on Earth (lower right) – (Photo: NASA).

Mars has two types of ice: frozen water and frozen carbon dioxide. The new study focused on the former.

A significant amount of water ice on Mars formed from snow mixed with dust falling on the surface over a series of ice ages spanning millions of years, creating a patchy ice interspersed with dust.

While dust particles may obscure light in deeper ice layers, they play a crucial role in explaining how groundwater pools can form in ice when exposed to sunlight.

Dark dust absorbs more sunlight than the surrounding ice, potentially causing the ice to warm and melt at depths of several tens of centimeters below the surface.

On the Red Planet, atmospheric effects make melting difficult on the surface, but these obstacles would not exist beneath a layer of dusty snow or glacier.

On Earth, dust in the ice can create cryoconite holes, which are small cavities that form in the ice as dust particles blown by the wind settle, absorb sunlight, and melt deeper into the ice each summer.

Eventually, as these dust particles move further away from sunlight, they stop sinking but still generate enough heat to maintain a pocket of meltwater around them.

These pockets could support a thriving ecosystem with simple life forms such as bacteria.

Co-author Phil Christensen from Arizona State University in Tempe, who leads the Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) camera operations on NASA’s Mars Odyssey orbiter, noted that he and his colleagues have previously discovered layers of dust-covered water ice exposed in canyons on Mars.

In the new study, they argue that in those areas, dust ice allows enough light for photosynthesis at depths of 3 meters below the surface, where liquid water pockets can exist without evaporating due to the insulating ice layer above.

Among these areas, the region between 30 and 40 degrees latitude on Mars, in both the northern and southern hemispheres, is identified as the most promising area for exploration.