The annual migration of giant sardines from East South Africa to the Indian Ocean represents the largest biomass migration on the planet.

The migration of wildebeests on their round trip through the Serengeti plains is one of the most impressive events on Earth, but it is not the largest animal migration. When measured by biomass, which refers to the total mass of a species in a specific area, the annual sardine migration actually surpasses that of the wildebeest, according to IFL Science.

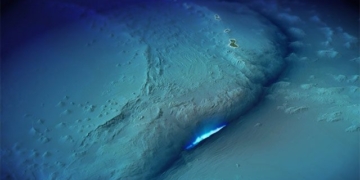

A school of sardines swimming past a shark during their migration.

Sardines migrate each year along the eastern coast of South Africa, with massive schools moving from the cold waters off Cape Agulhas northward to KwaZulu-Natal and into the Indian Ocean. These schools can stretch over 7 kilometers long, 1.5 kilometers wide, and 30 meters deep. Altogether, billions of sardines participate in this migration. Despite being one of the largest migrations on the planet, it also comes with downsides. The large number of sardines attracts numerous predators looking to feast, including dolphins, sharks, seabirds, and fur seals.

If sardines are easily targeted by predators, why do they continue to migrate year after year? Using genetic data, a 2021 study determined that the majority of sardines participating in the migration originate from the Atlantic, where the waters are colder. The short-term upwelling of cold water in the typically warm southern seas prompts the sardines to move. When this upwelling ends, they find themselves trapped in an environment they have not yet adapted to, facing many predators.

The research team concluded that the sardine migration is “a rare example of mass migration with no significant benefit” and is essentially a trap. However, William Sydeman, an ecologist and president of the Farallon Institute for Advanced Ecosystem Research in Petaluma, argues that sardines migrate to take advantage of temporary favorable ocean conditions in the Western Cape.

Professor Peter Teske from the University of Johannesburg suggests that the sardine migration could be a remnant of spawning behavior dating back to the Ice Age. The current habitat is the subtropical Indian Ocean, which was once a crucial development area for juvenile sardines with its cold water conditions. If this is correct, climate change could impact the future of sardines.