Rapa Nui Island, also known as Easter Island, located in Chile, is one of the loneliest places on Earth, situated in the vast waters of the South Pacific Ocean, 3,700 kilometers from the South American coast and 1,000 kilometers from the nearest inhabited island. Upon its discovery, the island was already home to two types of inhabitants: the Polynesians, who lived in a primitive state, and the monumental stone statues that represented a highly developed civilization.

Rapa Nui Island, also known as Easter Island, located in Chile, is one of the loneliest places on Earth, situated in the vast waters of the South Pacific Ocean, 3,700 kilometers from the South American coast and 1,000 kilometers from the nearest inhabited island. Upon its discovery, the island was already home to two types of inhabitants: the Polynesians, who lived in a primitive state, and the monumental stone statues that represented a highly developed civilization.

The current inhabitants of the island lack the advanced sculpting techniques needed to create such impressive stone statues, as well as the maritime skills required to travel thousands of kilometers across the sea. This raises intriguing questions: Who carved these statues? For whom were they made? What was their purpose? All of these mysteries cast a shadow over the island.

The history of Rapa Nui’s discovery is relatively recent. In 1722, the Dutch were the first to set foot on the island, naming it “Easter Island” on April 5, coinciding with Easter Sunday. The name Rapa Nui translates to “Stone Statue Island,” as designated by the island’s inhabitants.

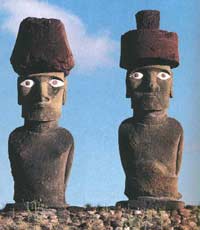

Subsequently, Spanish explorers and other European adventurers visited the island multiple times over the years. What fascinated these explorers the most was that this small, remote island still had residents living on it. More importantly, the island boasted hundreds of giant stone statues known as “Moai,” characterized by their unusually long faces, slightly upturned noses, thin protruding lips, broad foreheads tilted back, and large ears. The bodies often feature engravings of flying birds, with arms hanging at their sides. These distinctive features give the statues a unique presence that is immediately recognizable. Additionally, some statues wear cylindrical red hats, referred to as “Pau Cau” by the natives, which resemble pink crowns, adding an air of nobility and arrogance to the statues.

Out of the 600 statues, only about 30 are honored with red hats. The distribution of these hat-wearing statues is as follows: 15 on the southeastern coast, 10 on the northern coast, and 6 on the western coast. The statues adorned with red hats appear to be the nobility among the common statues.

Out of the 600 statues, only about 30 are honored with red hats. The distribution of these hat-wearing statues is as follows: 15 on the southeastern coast, 10 on the northern coast, and 6 on the western coast. The statues adorned with red hats appear to be the nobility among the common statues.

These revered statues have become symbols of the lonely island at the horizon’s edge. However, as we praise these statues, questions arise: What do they represent? How could the island’s indigenous people, with their primitive tools, create such monumental works?

In researching their origins, archaeologists and geologists found that the islanders had no knowledge of the statues’ histories; they, like us, were not involved in their creation.

The giant statues of Rapa Nui have captivated tourists, leading to numerous travelogues, memoirs, and descriptions, and they continue to grow in mystery. The statues share a uniform design: human figures with long, narrow faces, blank expressions, indicating they were crafted according to a single model. The unique style of these statues is unmatched anywhere else, suggesting they are a product of the island itself, not influenced by outside sources. However, some scholars argue that their design bears a resemblance to stone figures from the ancient cultures of the American Indians and the Maya in Tenochtitlan, Mexico. Could it be that ancient Mexican culture influenced these statues despite being thousands of kilometers away?

This possibility is unlikely because these statues weigh between 2.5 tons for the smallest and up to 50 tons for the largest, with some even wearing hats that add to their weight. How were these heavy stones quarried and transported over such distances to stand tall and firm? Furthermore, centuries ago, the island’s inhabitants had yet to discover iron tools.

So, who crafted these stone statues on the island when the local population lacked the means?

Archaeologists have analyzed the arrangement of these colossal statues and discovered the quarries located on the Ranorako mountain range. Hundreds of thousands of cubic meters of hard stone were quarried, with debris scattered everywhere. The completed stone statues were transported to distant locations for erection. At the “construction site,” hundreds of unfinished stones and statues remain, with one statue’s face completed but still attached to the mountain. It seems that only a few more cuts were needed to detach the statue, but the creators suddenly abandoned their work, as if they had realized something and left in haste.

Looking across the entire “construction site,” the scale is immense, and it is hard to imagine what could have caused all the workers to leave. The scattered stone fragments and debris resemble footprints left in a chaotic retreat. The remnants show deep chisel marks and shattered stone everywhere, indicating a once lively atmosphere of hard work.

The works at various stages of completion seem frozen in time. What happened on the island?

The works at various stages of completion seem frozen in time. What happened on the island?

Was it a volcanic eruption? The island was formed by this very volcano. However, geologists argue that while Rapa Nui is indeed a volcanic island, the volcano had long been dormant, long before humans inhabited it, and has remained stable since. Was it a tsunami or some other disaster that halted the work? The island’s inhabitants were accustomed to storms and would not panic at the sight of a tempest. If there had been a disaster, they could have resumed work afterward. Yet, they did not.

Why is that? Why is the creation of these giant stone statues a mystery, and why did the work stop abruptly at the quarry?

Many scientists who have studied the 600 statues scattered across the island and the scale and topography of the quarry sites believe that such a massive undertaking would require about 5,000 strong laborers. They conducted experiments to carve a medium-sized statue and found that it would take more than ten workers an entire year. Using wooden rollers was the only apparent solution for transporting the statues across the island. Moreover, this primitive method could theoretically move enormous objects anywhere on the island. Clearly, this approach demands significant labor, yet when Jacob Roggeveen visited the island, he noted that there seemed to be no trees at all. Therefore, without trees, how could they transport these colossal stone statues?

So how were these statues moved around the island?

Additionally, among the stone statues on the island, many are adorned with stone hats. These hats weigh between 2 and 10 tons, which presents another challenge: to place these hats on the heads of the colossal statues, at least a crane would be needed. With no trees on the island, and no wood available for rollers, what material could be used to construct a crane?

Furthermore, what did these 5,000 strong laborers eat and how did they live? In that ancient historical period, the island had only a few hundred indigenous people, who lived in a primitive state, relying on the scantest resources for sustenance. The island’s bark and occasional fish washed ashore could hardly satisfy their most basic needs.

Currently, the island has only about 1,800 residents, many of whom still rely on supplies from the mainland.

Currently, the island has only about 1,800 residents, many of whom still rely on supplies from the mainland.

Perhaps a religious force compelled the islanders to create these earthly wonders. However, the island’s natives were primitive people without any organized religion. It wasn’t until the 19th century, with the arrival of French missionaries, that they gradually adopted Roman Catholicism. The statues facing the sea represent a religion that even the islanders themselves do not fully comprehend.

The leader of the British Museum’s expedition, archaeologist Scot Trotter, emotionally and vaguely recorded in his memoir, “… the atmosphere on the island gives us the feeling that it once had a grand design that has now vanished, leaving behind a monumental spirit. But what was it? And what was its purpose?”

-75x75.jpg)