Intense rainfall and storms driven by climate change have compelled Japanese authorities to expand the network of floodwater tunnels beneath Tokyo.

Shortly after 5 AM on August 30, water began flooding the gigantic underground reservoir nicknamed “The Cathedral” in northern Tokyo. The torrent of water captured by security cameras was rain falling on the capital as Typhoon Shanshan made landfall in southwestern Japan, 600 km away, according to Reuters. “The Cathedral” and its extensive tunnel network have successfully protected the river basin in this megacity from flooding. However, with global warming leading to more severe weather, authorities need to upgrade the system.

“As temperatures rise, the amount of water vapor in the atmosphere increases, resulting in heavier rainfall,” said Professor Seita Emori from the University of Tokyo, a member of the Nobel Prize-winning climate science team in 2007. “We predict unprecedented levels of rainfall will occur as temperatures continue to rise in the future.”

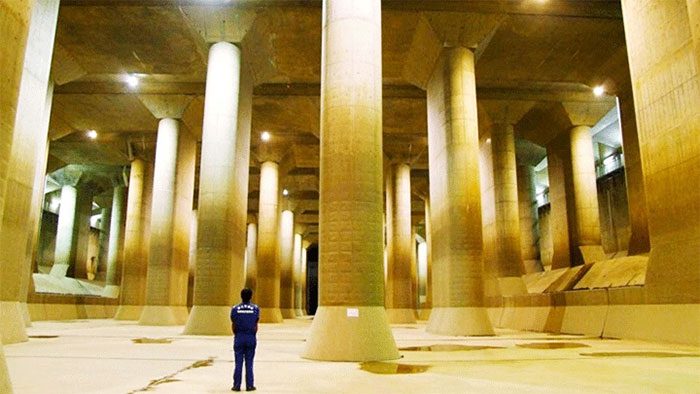

Pillars in the flood control tunnel system beneath Tokyo. (Photo: CBS).

Japan frequently faces various natural disasters, from earthquakes and volcanic eruptions to storms and landslides. The country is currently confronting unprecedented extreme weather due to global warming. This summer has been the hottest since 1898, while record rainfall in the north caused catastrophic flooding in July. In Tokyo, intense and sudden storms known as “guerrilla” storms are becoming increasingly common.

The “Cathedral” complex, officially named the Underground Water Discharge Channel of the Greater Tokyo Area, took 13 years and $1.63 billion to construct. Since its operation in 2006, the system has prevented over $1.06 billion in flood damage. This cavern-like structure can hold an amount of water equivalent to nearly 100 Olympic-sized swimming pools. Inside the complex are 59 massive pillars, each weighing 551 tons and standing 18 meters tall. When nearby rivers overflow, floodwaters are channeled through 6.3 km of underground tunnels before being directed to a reservoir.

Descending through six levels to the bottom of the reservoir is a unique experience. The system has a microclimate, being much cooler than above ground in summer and warmer in winter. Clouds of mist obscure the top of the pillars. The dark space is illuminated by natural light filtering through gaps in the ceiling. The towering pillars evoke ancient monuments, leading to the nickname “The Cathedral.” The first chamber is so deep and wide that it could accommodate the Statue of Liberty.

The system was activated four times in June, surpassing the total number of activations for the previous year. During Typhoon Shanshan, it collected enough water to fill nearly four Tokyo Dome stadiums before safely releasing it into the Edogawa River and out to sea. “Compared to previous years, heavy rainfall tends to fall all at once,” shared Yoshio Miyazaki, an official at the Ministry of Land responsible for the tunnel complex. “If this system did not exist, water levels in the main Nakagawa River and its tributaries would be much higher, resulting in flooded homes and even loss of life.”

Even so, the system could not prevent flooding of over 4,000 homes in the river basin after heavy rainfall in June 2023. This flooding prompted authorities to undertake a seven-year project worth $250 million to reinforce levees and drainage in the area. Closer to central Tokyo, another major project is underway to connect overflow channels from the Shirako and Kanda rivers. When completed in 2027, this system will divert floodwaters through 13 km of tunnels to Tokyo Bay.

Tokyo’s sewer network is designed to handle rainfall of up to 75 mm per hour, but the increasing number of localized storms can bring over 100 mm of rain, overwhelming the system, according to Shun Otomo, a construction site manager in Tokyo. “For example, if there is a torrential downpour in the Kanda river basin, we can utilize the absorption capacity in the areas that aren’t experiencing rain,” he said.