According to a study published in Nature Communications on October 1, the James Webb Space Telescope from NASA has uncovered new clues about the surface of Charon, the largest moon of the dwarf planet Pluto.

This is the first time that traces of CO2 (carbon dioxide) and H2O2 (hydrogen peroxide) have been detected on the surface of this celestial body. Both are in a frozen solid form and have been added to the list of water ice, ammonia-containing compounds, and organic materials previously recorded on Charon’s surface.

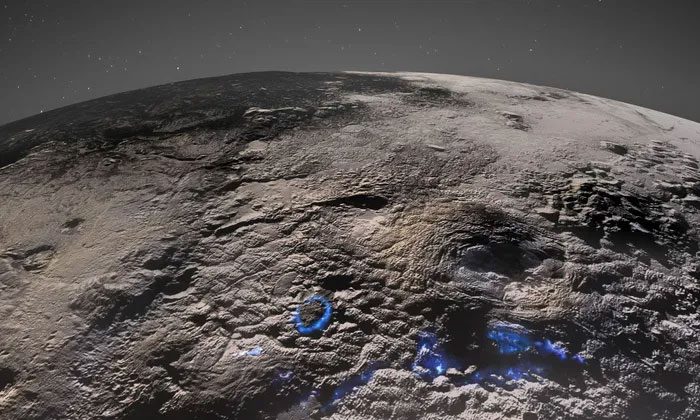

Pluto’s surface. (Illustrative image: AFP/TTXVN).

With a diameter of about 1,200 km, Charon is about half the size of Pluto. Research from NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft in 2015 showed that Charon’s surface is covered with water ice. However, detecting chemical compounds at specific infrared wavelengths was a significant challenge until the Webb telescope was deployed.

The Webb telescope has further detected CO2 and H2O2, both of which play crucial roles in helping to decode Charon’s formation history and surface processes. According to the study, H2O2 may form from ultraviolet radiation and solar wind striking Charon’s water ice surface over long periods. Meanwhile, CO2 could arise from meteoroid impacts, bringing primordial material from the time of Charon and Pluto’s formation about 4.5 billion years ago to the surface.

Scientist Carly Howett from the New Horizons project noted that the James Webb telescope helps uncover many “traces” of compounds that humans could not previously see, expanding our understanding of the structure and formation processes of distant celestial bodies.

Discovered in 1978, Charon orbits Pluto at a distance of about 19,640 km, significantly less than the distance between Earth and the Moon (384,400 km). Although its surface is predominantly gray and silver, the polar regions of Charon exhibit a reddish-brown color, primarily due to the presence of organic materials.

Pluto and Charon are located in the Kuiper Belt, a remote and icy region beyond the Solar System. At a distance of over 4.83 billion km from the Sun, both celestial bodies are too cold to support life but contain many clues about how planets and moons in the Solar System formed.

The findings from Webb not only enhance our understanding of Charon but also contribute to the overall picture of small celestial bodies in the Solar System.

Ms. Silvia Protopapa from the Southwest Research Institute, a member of the research team, emphasized that every object in the Solar System is an important piece of the puzzle that scientists are trying to solve. Observations from Webb confirm that CO2 and H2O2 on Charon’s surface are products of radiation and impact processes, contributing to a better understanding of the formation and resurfacing processes of celestial bodies. These discoveries not only enhance our understanding of Charon but also open new prospects for studying other distant celestial objects, bringing scientists closer to unraveling the profound mysteries of the universe.