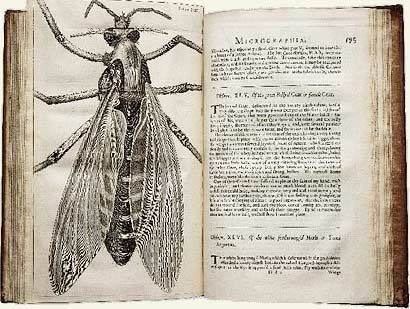

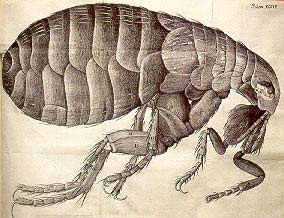

In 1665, a groundbreaking book titled “Micrographia” was published in England, sparking discussions in the scientific community across England and Europe. This book contained fundamental discoveries in biology, featuring 60 large illustrations drawn by the author himself, including a louse magnified to several dozen centimeters in length, a large nit occupying an entire page, the complex eye structure of a fly, and the intricate details of bird feathers, all presented with meticulous detail. The author of this book was Robert Hooke, a 30-year-old English botanist.

Illustration of a flea from Hooke’s book “Micrographia”

published in 1665 (Photo: sfr.ee.teiath)

Robert Hooke was born on July 18, 1635, in a rural village on the Isle of Wight, near the southern coast of England, into the family of a Protestant minister. As a child, he was often frail but exceptionally intelligent and studious; within just two weeks, he completed Euclid’s introductory mathematics book. He spent his days crafting mechanical devices, ships, water mills, pendulum clocks, and wooden airplanes. At the age of thirteen, after his father’s death, he had to seek work at a painting workshop, learning portrait painting to make a living. However, the smell of oil paint and solvents made him dizzy and ill, forcing him to leave the job. He then joined the laboratory of the newly established Royal Society of England, where he began by cleaning experimental tools. His thirst for knowledge drove him to self-study and attend classes at Oxford.

|

Robert Hooke (Photo: wikipedia) |

At the age of 26, Hooke published his first book, which studied surface tension. In the mid-17th century, many scientists in Europe were inclined to create and use optical instruments to study nature, and Hooke was among those who contributed to this trend. After four years of work, he published his research findings in the famous book “Micrographia”. In this book, he meticulously noted the methods he used for his research: “… I chose a small room with only one window facing south. About a meter from the window, I placed a table with a microscope for my studies… I had to use a glass ball or a biconvex lens, with the convex side facing the window to capture as much light as possible to create a source of illumination. I then placed a piece of oiled paper between the light source and the object I was observing, along with a powerful magnifying glass to concentrate as much light as possible through the oiled paper and onto the object, while also being careful to estimate how long the oiled paper would be exposed so that it wouldn’t get too hot and catch fire..”.

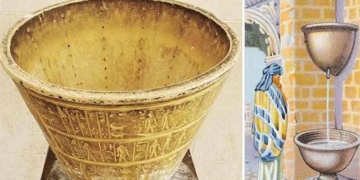

Hooke’s observations demonstrated his meticulous dedication to research: “To be able to work even on days without sunlight and late at night, I constructed a vertical instrument with three horizontal arms. On one arm, I placed a movable oil lamp, on another arm, a glass ball containing clear liquid, and on the third arm, a biconvex lens that could move in various directions”. With these self-made tools, Hooke conducted botanical research. In his book, he recorded his findings: “Through the microscope, I observed pieces of cork (liège) and noticed they had a structure resembling small chambers and holes. I used a knife to cut them into thinner pieces, and I clearly saw that these pieces had a structure like honeycomb, with small chambers. I counted carefully and found 60 cells (the term “cell” comes from the Latin “cellula,” meaning small room; thus, Hooke was the first to coin and use the term ‘cell’), which were closely packed in an area measuring 1mm, meaning there would be over a million (precisely 1,666,400) cells in a cork area of 6.5cm2, an astonishingly large number.” After that, Hooke decided to further investigate the microscopic structures he had just discovered.

Just as Hooke’s book “Micrographia” was published in 1665, he presented his observations to the Royal Society of England in a report titled “The Structure of Cork through Magnifying Lenses.” The following year, he was elected as a member and secretary of the Royal Society, a position he held for 15 years. At the age of 36, he conducted an experiment on himself to study the effects of low-pressure environments: he sat in a small chamber and endured very low pressure (only 1/4 of normal pressure) while recording the symptoms he experienced.

|

| Illustration of a flea from Hooke’s book “Micrographia” published in 1665 (Photo: roberthooke.org) |

Hooke was a passionate scientist, often seen in the laboratory from early morning: small, short, and thin, with a slightly hunched posture and a face that was not particularly handsome due to a wide mouth and a pointed chin. He was humble and generous; throughout his years at the Royal Society and the university, he never complained about his salary. His straightforward and often irritable nature led to conflicts with colleagues (it later became known that his poor health since childhood caused him to have a poor appetite and suffer from insomnia). His debates with Isaac Newton (1642-1727) became famous, as it is believed that Hooke informed Newton about his physics research findings, facilitating Newton’s discovery of some new laws. However, it is also possible that Newton independently discovered these laws, which is why he did not clearly acknowledge Hooke’s contributions. Regardless, this conflict became significant enough that Newton was only elected as President of the Royal Society after Hooke’s death (during 1703-1727).

Hooke was not only a renowned botanist for discovering cells, he was also a distinguished astronomer. He made significant scientific contributions, including the invention of the telescope, observations of celestial bodies’ rotational movements, proposing that the freezing point of water is 0°C, formulating the mechanical theory of heat, and studying the origins of fossilized objects. He was also a talented architect, involved in the design and reconstruction of many large buildings and areas in London after the Great Plague (in 1665) and the Great Fire (in 1666).

Robert Hooke’s fame resonated not only during his lifetime but also continued for centuries afterward, with the notable exception that no one has ever preserved a portrait of him, and his burial site remains unknown.

Seven years after Hooke discovered cells, in 1672, Malpighi also described small sacs in plant structures. 140 years later, in 1805, a German physician and naturalist, Lorenz Oken (1779-1851), also affirmed: “All living organisms are composed of cells.” However, it took 174 years after Hooke’s discovery for cells to be confirmed as the basic structural unit of both animals and plants, thanks to the work of Schleiden and Schwann.

Source: The book “20 Famous Biologists” by Tran Phuong Hanh, Thanh Nien Publishing House