The Paris Gun was designed by Fritz Rausenberger, an engineer from the German arms manufacturer Krupp, with an effective range of up to 125 kilometers—far surpassing anything that had been created before.

At 7:15 AM on March 23, 1918, the residents of Paris were awakened by a loud explosion near the Seine River dock. Fifteen minutes later, another explosion rang out from Charles V Street, followed by a third explosion on Strasbourg Boulevard near the Eastern Station. The lack of sound from the cannon indicated that the shells must have been fired from a very long distance.

Many theories were proposed. It took several days after the bombings started for the French to realize the full range and capabilities of this weapon. The cannon, now referred to as “The Paris Gun”, was one of the most formidable weapons manufactured during World War I, capable of firing shells from an astonishing distance.

Fritz Rausenberger and his colleagues spent considerable time developing the super cannon, which weighed 256 tons and measured 34 meters in length. Within a year, Rausenberger created a working prototype that successfully fired its first test shot on November 20, 1917. After further experiments with various propellants and shells, Krupp engineers managed to extend the gun’s range to 125 km—surpassing anything previously manufactured.

The super cannon could fire shells from a distance of 120km. (Image source: Wikimedia Commons).

To achieve the desired specifications, the cannon barrels were equipped with an internal liner that reduced the bore size from 380 mm to 210 mm. This liner was 31 meters long and extended an additional 14 meters beyond the original barrel. An extension was bolted to the barrel to enclose and reinforce the liner. Additionally, the barrel was extended by another 6 meters with a smoothbore attachment, resulting in a total barrel length of 37 meters. The sheer size and weight of the gun necessitated that an external mounting system be clamped along the barrel to prevent it from sagging under its own weight.

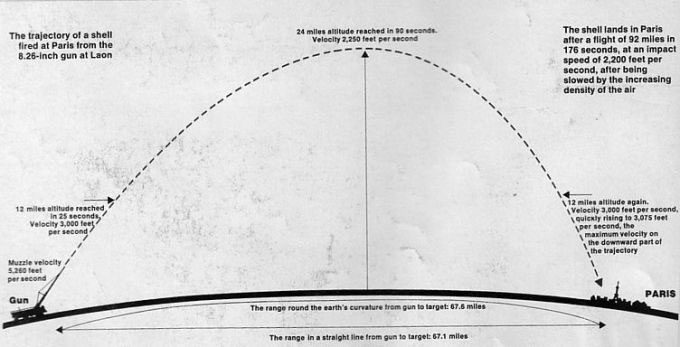

The cannons were installed on Mont-de-Joie, north of Crépy-en-Laon, at three firing positions 120 km away from Paris. The cannons were not aimed directly at Paris but slightly to the left to compensate for the deflection that the shell would experience as the Earth rotated beneath it. At a firing angle of 50 degrees, the shell soared into the stratosphere, reaching a maximum altitude of 40 km—a height record that stood for nearly 25 years until the Germans tested the first V-2 rocket in 1942. At that altitude, air resistance significantly decreased, increasing the horizontal range.

The trajectory of shells fired from The Paris Gun.

The extreme range required a very high velocity, causing significant wear on the barrel, to the extent that with each consecutive shot, a considerable amount of steel was worn away from the barrel. Consequently, each shell was produced with an increasing diameter to accommodate for the wear. The shells were numbered and had to be fired in the correct order; otherwise, a shell could become lodged in the barrel and explode prematurely. Such an incident occurred on March 25, destroying Gun No. 3 and killing several soldiers.

After firing 60 rounds, the barrel was sent back to Krupp’s factory in Essen to be re-bored to a diameter of 224 mm, after which a new set of shells was issued. After firing another 60 rounds, the barrels were re-bored a second time, this time to 238 mm.

Despite The Paris Gun’s incredible range and the challenges in operating it, it was not an effective weapon. The average weight of a shell was 106 kg, but most of that weight was in the shell’s body, which needed to be reinforced to withstand the immense firing pressure. As a result, the amount of explosives it carried was only 7 kg—too little to create a significant explosion. A shell that fell in the Tuileries Garden, a famous park in Paris, left only a 3 to 4 meter deep and 1 to 1.2 meter wide crater. Even when shells struck buildings and exploded inside, there was often little to no visible damage outside.

A report prepared by the U.S. Army in 1921 noted the weapon’s unimpressive impact: “The visible destruction to property is so minor that hardly anyone in the city knows what damage the explosions they occasionally hear are causing.”

The terrifying range of The Paris Gun had a major drawback—lack of accuracy. The cannon could not aim at anything smaller than an entire city, and even within Paris, the shells fell everywhere without hitting anything significant. From March to August, the three Paris Guns fired approximately 367 shells (though French records note 303 shells), but only 183 of those fell within the city limits. The shells killed 250 people and injured 620, with the deadliest incident occurring on March 29, 1918, when a shell struck the roof of St-Gervais-et-St-Protais Church, killing 91 worshippers and injuring 68 when the roof collapsed.

The Paris Gun fired its last shell on the afternoon of August 9, 1918, after which it was pulled back to Germany as Allied forces began to threaten its position. When the war ended, the guns were completely dismantled, and Krupp destroyed most of the research and development documentation related to the project. Today, the only evidence of The Paris Gun’s existence is the concrete gun emplacements still found in the forest near Crépy.