After each report on the storm’s center position, mark the storm’s location on a map. You will find that, while there are some variations, the storm’s center typically follows a parabolic and linear path. Storms move in a very predictable manner on Earth.

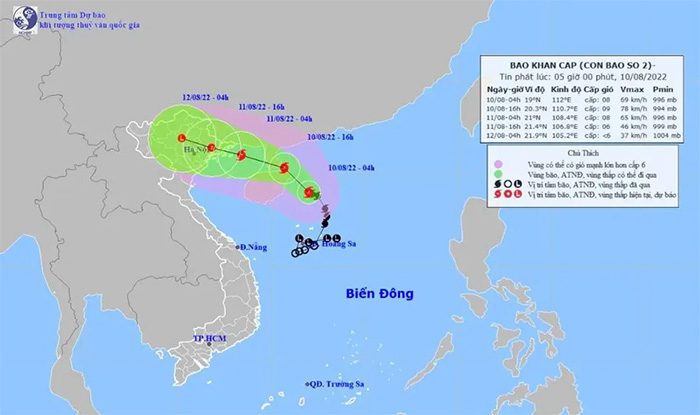

Path of Storm No. 2/2022.

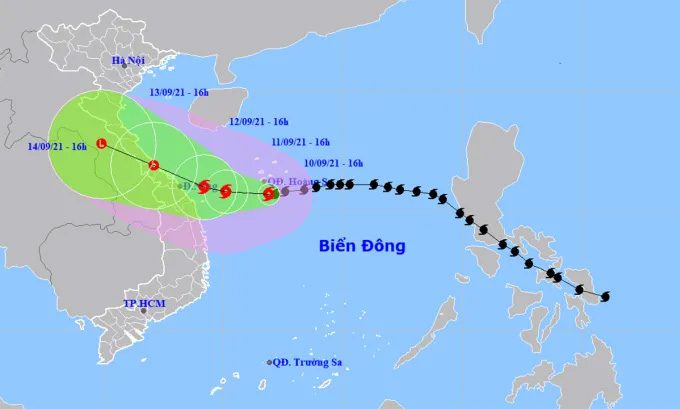

Path of a storm in September 2021.

The forecasts provided by meteorological stations are primarily based on the movement patterns of storms. There are two types of forces that cause storms to move: internal forces and external forces. Internal forces are generated within the storm itself. Since a storm is essentially a swirling column of air rotating counterclockwise, the movement direction of each air particle is influenced by the Earth’s rotation, resulting in a deflection effect.

This deflection effect in the Northern Hemisphere causes air particles in the storm to tend to move to the right. Furthermore, as the latitude increases, the impact of this deflection becomes stronger. This phenomenon leads to winds from the north blowing towards the west, where many air particles have shifted slightly to the north. Conversely, winds from the south blowing towards the east, where there are fewer air particles, have shifted slightly to the south. Thus, the air quality in the southern part of the storm is greater than that in the northern part, causing the center of the storm to shift northward. This net weight can be attributed to the main internal force in the storm’s path. Additionally, the air within the storm is rising.

High-altitude air, under the influence of the Corriolis force (the effect of Earth’s rotation on moving objects), tends to move westward, which can also be attributed to the storm’s internal forces. The combined effect of these two types of internal forces gives the storm a tendency to move northward with a westward deviation.

External forces are the driving forces that propel the storm when the surrounding air mass moves on a larger scale. In summer and autumn, the Pacific Ocean often has a high-pressure system (commonly referred to as subtropical high pressure). The wind direction around this high-pressure area is related to the storm’s movement path. Storms typically form in the vicinity of the southern part of the Pacific high-pressure system, where east winds prevail, causing the storm to move westward.

The combination of internal and external forces leads to the storm’s movement usually following a specific pattern. However, during its movement, the storm is significantly influenced by the subtropical high pressure over the Pacific Ocean.

Initially, when the storm is located to the south of the subtropical high, it typically moves northwest. Once it approaches the western edge of the subtropical high-pressure belt, it enters the northwestern part of the high-pressure center, at which point the external forces acting on it change, causing it to shift eastward. Combined with the internal forces, this results in a directional change towards northwest.

Due to the strength of the subtropical high pressure, which extends to the west and narrows to the east, along with varying discontinuities, the storm’s path can differ. If the subtropical high pressure extends further west and strengthens, the storm’s path will also shift southward, moving directly west. Conversely, if the subtropical high pressure to the north of the storm retreats eastward or becomes discontinuous, the storm may move north where there are breaks or towards the west of the high-pressure area, then curve northeast.

In summary, the storm’s path is typically parabolic. During its movement, the storm rotates and travels, and its area of high winds expands. When formed over tropical waters, its diameter can reach around 100,000 meters. As it moves towards the vicinity of 30 degrees north latitude, its diameter can increase tenfold from its initial size, continuing to move forward. The storm’s intensity gradually decreases, and the wind range diminishes until it eventually dissipates.

Typically, storms pass near the border with China before moving towards Japan, thus primarily affecting the provinces of Guangdong, Hainan, Guangxi, Taiwan, Fujian, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, and the city of Shanghai. The coastal areas of Shandong and the Liaodong Peninsula may occasionally experience some impact, but storms rarely affect northern provinces or inland areas. Only when the western part of the Pacific subtropical high pressure affects the Jiangnan region of China do storms make landfall in the southeastern coastal areas and move inland.

Storms originate over the ocean, and a mature storm can produce extremely strong winds, with speeds exceeding level 12 capable of generating waves several dozen meters high, capable of sweeping away large vehicles weighing tons.

After making landfall, storms continue to wreak havoc in coastal areas, uprooting trees, demolishing buildings, and destroying crops. However, once they move deeper inland, friction with the ground gradually reduces wind speed and intensity. At this point, they release heavy rainfall, causing landslides, flooding, and breaching levees and fields. There have been instances where, after making landfall, a province far from the sea, like Henan, experienced over 1000 mm of rain within a few days, resulting in widespread flooding.