Scientists Discover a Ring Around a Dwarf Planet Located Beyond Neptune’s Orbit

The debate continues over whether Pluto should be classified as a planet. When asked, astronomers typically respond that if Pluto is a planet, then many other celestial bodies in the Solar System should also be classified as planets. One such body is Haumea, a lesser-explored rock in the Kuiper Belt, known for being one of the strangest large objects in the Solar System. Currently, a group from NASA is conducting research on the peculiarities of Haumea.

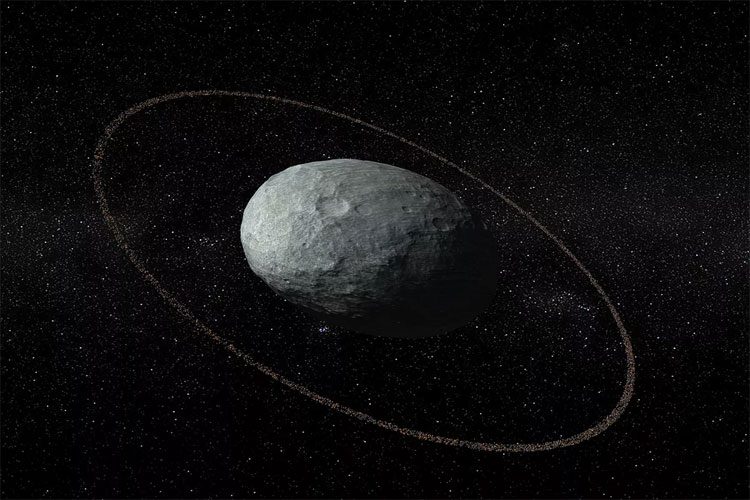

Jose Luis Ortiz, an astronomer at the Institute of Astrophysics of Andalusia, Spain, and his colleagues have discovered a large ring around the dwarf planet Haumea, situated outside Neptune’s orbit. Haumea takes about 284 years to complete an orbit around the Sun, according to Science Alert. The research findings were published in the journal Nature on October 11.

The dwarf planet Haumea has a ring around it. (Photo: IAA-CSIC/UHU).

Rings are typically found around the giant planets in the Solar System, including Saturn, Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune. In 2013, astronomers also identified two rings around the asteroid Chariklo, which orbits between Jupiter and Neptune.

Scientists from 10 different laboratories observed the dwarf planet Haumea using 12 telescopes across Europe as it moved in front of a star named URAT1 533–182543.

The results indicated that Haumea’s ring is approximately 70 km wide and has a radius of 2,287 km. The small particles in the ring complete a rotation as this dwarf planet spins three times around its axis. Haumea has an unusually elongated ellipsoidal shape. Its dimensions across three axes in space are 2,322 km × 1,704 km × 1,138 km. The research team did not detect any signs of an atmosphere on Haumea.

Because Haumea is very distant from Earth, obtaining accurate data on this peculiar object is challenging. No human spacecraft has ever visited this object, partly because it is too small and far away to be accurately measured with telescopes on Earth. Therefore, researchers often rely on their favorite tool – computer modeling – to study it.

Haumea takes about 284 years to complete an orbit around the Sun.

However, computer models require a certain amount of input data to make predictions, and so far, we have only discovered a few things about Haumea. One is how fast it rotates – a day on its surface lasts only four hours, significantly shorter than the day of any similarly sized object in the Solar System.

Dr. Noviello, the lead author of the study, stated that this object also has several “siblings” – small icy bodies that orbit similarly around the main object – resembling moons, but not classified as such. Therefore, to understand the strange characteristics of this object, researchers had to look back in time and investigate its history – and of course, make some estimates.

This is a two-step process. First, Jessica Noviello, now a postdoctoral researcher at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, developed a model requiring only three distinct inputs – size, mass, and rotation speed of Haumea. The output from this first model provides information such as the size and density of the object’s core, which is then fed into another model used to iteratively determine its formation process, reflecting what Haumea looks like today.

Making slight changes to the input parameters of the final simulation will yield a set of expected results that can be compared with actual measurements. However, it also highlights some intriguing possibilities regarding how Haumea formed.

First, it likely experienced a massive impact during its early formation stage. This collision would have caused its rotation speed to spike due to inertia. Additionally, the impact may have expelled parts of Haumea, forming the small icy bodies now referred to as its “siblings.”

Haumea may have been struck by a massive object during its early formation stage.

The creation of those small icy bodies requires a second, more prolonged process, but is believed to have a significant impact. The rapid rotation causes denser rocks to slide towards the core of the dwarf planet, displacing those rocks. Since they, like all types of rocks outside the universe, are radioactive, they started melting the water ice that was forming on Haumea’s outer shell.

Some of the water then flowed into the core, creating a clay-like substance, and the rapid centripetal force subsequently shaped the elongated form of the object we see today. Moreover, some of the icy spheres lost their grip on the main body and shattered into smaller icy bodies that continue to orbit with their dwarf planet mother.

At this point, all these results come from simulation models, but they make sense both logically and scientifically. However, it will still take time before we gather any specific data about Haumea or its Kuiper Belt siblings. Until then, astrophysicists will have to be satisfied with results from studies like Dr. Noviello’s team, which have been recently published in the Planetary Science Journal.