Turn on the light, and the mosquitoes vanish. Turn off the light, and their annoying buzzing resumes. Mosquitoes always find you, waking you up with their incredibly irritating bites.

Surely, everyone has experienced the situation of turning off the lights and drifting off to sleep only to hear the buzzing of a mosquito. It’s a mosquito hunting you. “Its dance” begins.

If you turn on the light, the mosquito disappears. When you turn off the light, “the hunt” continues. The buzzing of mosquitoes is extremely bothersome, and even in the dark, they always manage to find you, waking you from sleep with bites on any exposed skin.

Mosquito bites carry the risk of transmitting diseases such as dengue, yellow fever, malaria, and Zika (Image: mycteria/Adobe).

How can these blood-sucking creatures find you so adeptly? Can they see in the dark? Researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara, have finally found the answer.

They have demonstrated that mosquitoes have an extraordinary ability to locate prey in the dark. Mosquitoes can detect infrared light from body heat. This light helps them accurately pinpoint the location of their victims and plan their attack.

The primary concern when bitten by mosquitoes is that some species transmit diseases to humans, including Zika, dengue, yellow fever, and malaria. They are responsible for over 400,000 malaria-related deaths worldwide each year.

The research team analyzed the behavior of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, which cause over 100 million cases of yellow fever, dengue, and Zika each year. They discovered that these mosquitoes can see infrared light when hunting at night and explained how this phenomenon occurs.

After determining that Aedes aegypti can see infrared light, they conducted experiments to prove it. They confined female mosquitoes in a cage and set up two areas to monitor their activity.

One area used sensors emitting infrared light that radiated energy similar to human skin temperature, combined with CO2 pumps at concentrations like those exhaled by humans. The second area had no infrared source.

The results showed that most of the trapped mosquitoes flew toward the area emitting infrared light at approximately 34 degrees Celsius, equivalent to human skin temperature. These mosquitoes could detect infrared light from up to 70 cm away.

Scientists also explained why previous studies had failed to identify this capability in mosquitoes. These creatures utilize information from various signals.

They seek infrared light, CO2 concentrations, and body odors. Experiments that focused solely on infrared light did not yield consistent results.

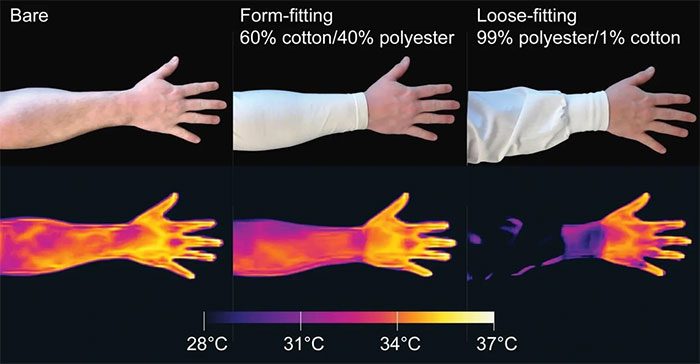

Different fabrics have varying abilities to block infrared light. From left to right: bare arm, arm wearing a tight shirt made of 60% cotton and 40% polyester, and arm wearing a loose shirt made of 99% polyester and 1% cotton. (Image: DeBeaubien, Chandel/UCSB).

Additionally, the research team hypothesized that infrared light travels through the air in electromagnetic waves, which then stimulate certain nerve cells in mosquitoes. This is how they detect infrared radiation, rather than actually seeing infrared light with their eyes.

These heat-sensing neurons are located on their antennae. When the antennae are clipped, they lose the ability to detect infrared light.

However, this sensing ability is still not strong enough for Aedes aegypti to see infrared light in the dark from a distance of up to 70 cm.

The researchers believe that they may possess certain rhodopsin proteins (a light-sensitive pigment) that function as heat detectors. More than ten years ago, similar behavior was observed in fruit flies.

The research team also found that two out of the ten rhodopsins in mosquitoes are located in neurons at the tips of their antennae along with temperature sensors that detect infrared light.

They concluded that the temperature sensors detecting infrared light operate at a distance of about 30 cm, where infrared light energy is strongest, while the two rhodopsins function when the infrared light is weaker.

All these factors help mosquitoes detect you in the dark. They hover around until they pick up these signals and then rush toward you.

The researchers also noted that loose-fitting polyester clothing can help prevent mosquitoes from detecting infrared light. However, exposed areas like hands, feet, and face remain vulnerable to their attacks.

These findings could be significant for people living in tropical and subtropical regions, where mosquitoes are abundant. By understanding their characteristics, individuals can find ways to avoid mosquito bites and reduce the risk of contracting the aforementioned diseases.