Queen Hatshepsut ruled ancient Egypt in the 15th century BCE and achieved many significant accomplishments, but her name was later erased.

Ruling ancient Egypt is typically viewed as a male-dominated role, yet one woman broke this tradition in the 15th century BCE: Hatshepsut. Despite her achievements during her 21-year reign that positioned her among Egypt’s greatest pharaohs, a purge campaign eradicated all traces of her existence shortly after her death.

A sphinx statue with the face of Queen Hatshepsut. (Photo: Miguel Cabezón).

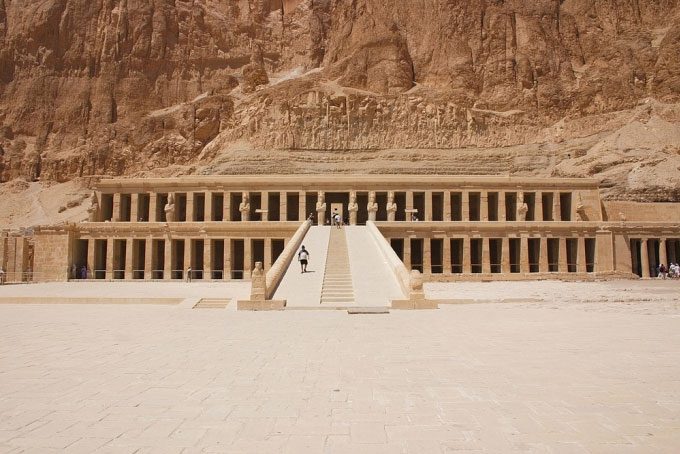

Hidden from history for 3,500 years, in ancient times, Hatshepsut was a far more significant figure than the famous Cleopatra. During her reign, this queen oversaw the construction of numerous magnificent structures, including the impressive mortuary temple of Deir el-Bahari near the Valley of the Kings, while maintaining peace and prosperity in the kingdom.

However, her rule lacked a solid foundation. As the daughter of Pharaoh Thutmose I and his wife Ahmose, Hatshepsut became queen by marrying her half-brother, Thutmose II. After her husband’s death in 1479 BCE, she was appointed as regent for her stepson, Thutmose III, who was too young to govern.

Although she was expected to relinquish power once Thutmose III came of age, Hatshepsut had other plans and declared herself pharaoh, holding the throne until her death in 1458 BCE. To solidify her position, she depicted herself as a man in countless statues and murals, donning the attire of a pharaoh along with a false beard.

However, her astute leadership was the key factor in maintaining her throne. One of her greatest achievements was a brilliantly successful expedition to the land of Punt, near the Red Sea. This expedition, led by her, brought back vast resources including gold, ivory, and exotic animals.

The temple of Hatshepsut in the Valley of the Kings in Luxor, Egypt. (Photo: Mirek Hejnicki).

After Hatshepsut’s death, Thutmose III finally had the opportunity to rule. However, he began to destroy all monuments and erase any mention of her name. Despite being a successful military pharaoh himself, he seemed displeased to have waited so long to ascend the throne and chose to consolidate his stepmother’s achievements into his own dynasty.

It wasn’t until 1822 that archaeologists rediscovered Hatshepsut’s name while decoding hieroglyphics at Deir el-Bahari, marking the beginning of efforts to restore the damages caused by Thutmose III and reconstruct the story of the most powerful woman in ancient Egypt. In 1903, the famous Egyptologist Howard Carter found the empty sarcophagus of the queen in the Valley of the Kings. It took scientists another century to identify her mummified remains on the floor of a nearby tomb.

In the years that followed, experts uncovered remnants of many destroyed structures bearing Hatshepsut’s name, often defaced or covered with the names of male pharaohs. Ultimately, all Thutmose III achieved was to add intrigue to the story of Hatshepsut, the queen whose journey to power is considered one of the most remarkable periods in ancient Egyptian history.