The effort to capture the movement of horses that the naked eye could not perceive led a photographer to develop the technique to create the first motion picture.

Horse painting reached its peak in the 19th century when horse racing became a popular sport. However, despite attempts to depict racing scenes, many artists realized they did not fully understand horses, especially how they moved at full gallop. Horses ran so quickly that the human eye could not keep up with their movements, which meant that the process of drawing horses often relied heavily on imagination. By the end of the 19th century, significant changes began to alter how artists depicted horses, according to Amusing Planet.

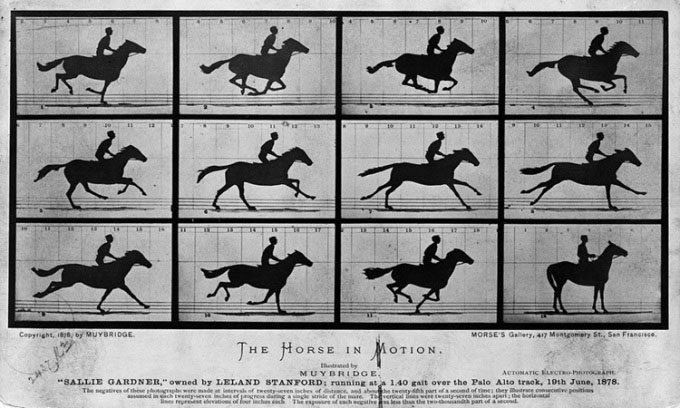

12 original photographs of the racehorse Sallie Gardner. (Photo: Amusing Planet).

In 1872, industrialist Leland Stanford, the founder of Stanford University, hired British-American photographer Eadweard Muybridge to photograph Occident, his favorite horse, in motion. At that time, photography was a slow process, requiring several seconds of exposure to create an image, meaning the subject had to remain still during the exposure time. Any subject that moved too much would appear blurred.

Initially, Muybridge believed it was impossible to capture a clear photograph of a moving horse, but after experimenting with various equipment and chemicals, he achieved satisfactory results. Muybridge had to pause his experiments for two years due to allegations related to the death of his wife’s lover.

Muybridge returned to work for Stanford in 1876, continuing to refine and improve the photography process. Shortly after, he successfully captured an image of Occident running at racing speed with all four hooves off the ground. Stanford was thrilled and encouraged Muybridge to use multiple cameras to create a series of images that would capture the entire gait of the horse. This time, Muybridge was asked to photograph another of Stanford’s horses named Sallie Gardner.

Capturing the action of a galloping horse was not easy. Muybridge needed to take multiple photographs in a short period, with each exposure lasting only a few thousandths of a second. To accomplish this seemingly impossible task, Muybridge used 12 modern cameras of his own design, lined up like cannons parallel to the horse’s race track. The shutter of each camera was triggered by a wire trap stretched across the track, activated by the horse’s legs. As the horse dashed past the wire, the sound of the camera shutters firing in succession resembled the sound of a machine gun.

Muybridge’s short film first recorded fleeting details that the naked eye could not perceive at high speeds, such as the position of the legs and the angle of the tail. Muybridge’s groundbreaking achievement confirmed that when a horse is fully airborne, its legs tuck underneath its body rather than extending forward and backward. He also prepared a short clip, using 12 still images he captured with a device called the zoöpraxiscope, the precursor to the motion picture projector. This 2-second motion clip titled “Sallie Gardner at a Gallop” is considered the first motion picture in the world.

Muybridge’s work was widely showcased around the globe. As Muybridge seemed to capture everyone’s attention, Stanford sought to undermine him. Subsequently, the Royal Academy of Arts in Britain, which had previously offered to fund Muybridge’s research into animal motion photography, ceased its financial support. Ultimately, Muybridge sued Stanford, but the case was dismissed by the court.

Muybridge began seeking funding elsewhere and received support from the University of Pennsylvania. Under the university’s sponsorship, Muybridge produced tens of thousands of photographs capturing moving people and animals. This collection was published in a large catalog featuring 780 slides and 20,000 images. Muybridge’s research significantly contributed to the development of biomechanics.