New analysis based on data from India’s Pragyan lunar rover has revealed many surprising findings.

Pragyan is a self-contained rover that was deployed by the Chandrayaan-3 mother spacecraft during its mission in 2023. So far, Pragyan has been in hibernation on the Moon for 11 months and remains unresponsive.

Despite this, scientists on Earth continue to analyze the intriguing dataset it collected during its brief operational period.

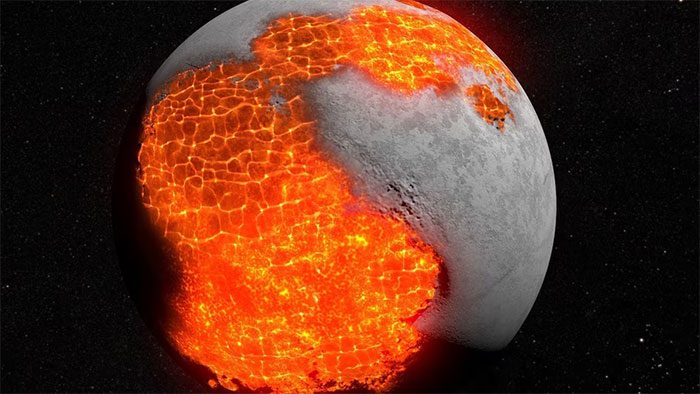

The early Moon had a global magma ocean – (Graphic: NASA).

Recently, a study published in the scientific journal Nature revealed a “dead ocean”. According to a team led by the Physical Research Laboratory (PRL – India), Pragyan’s measurements indicated a unique mixture of chemical elements in the lunar soil (regolith) around the lander that is relatively uniform.

This regolith is primarily composed of a type of white rock called ferroan anorthosite. Notably, the soil sample collected by Pragyan in the Moon’s South Pole region has a composition that is “intermediate” between two samples collected from two equatorial sites by the U.S. Apollo 16 mission and the Soviet Luna-20 mission in 1972.

This suggests that, despite some differences, lunar soil shows significant chemical similarities between the South Pole and the equator. This reinforces the idea of a global ocean that once covered the surface of this celestial body when it was still “in its infancy.”

However, this ocean is unlike what we see on Earth today; it resembles the primordial Earth more: It was a magma ocean, meaning “water” that was entirely molten rock.

The hypothesis of a global magma ocean on the Moon has existed for quite some time, referred to as the “Lunar Magma Ocean (LMO) model.” This serves as clear evidence that it indeed existed.

These results also fit neatly into a larger hypothesis regarding the formation of Earth’s satellite.

Many scientists believe that Earth was initially isolated, but a planet named Theia, roughly the size of Mars, collided with it 4.5 billion years ago.

After the impact, part of the primordial Earth and Theia merged to form the current Earth, while smaller debris was ejected into orbit and gradually coalesced to form the Moon.

The magma ocean existed from the time of formation and persisted for tens or hundreds of millions of years afterward.

The cooling and crystallization of this magma ocean eventually led to the formation of ferroan anorthosite, which constituted the Moon’s first crust. The representatives of this ferroan anorthosite are the mysterious white rock fragments rich in anorthite minerals that Apollo 11 discovered over half a century ago.