While the primary mirror of the world’s largest optical telescope spans 39 meters, the lightest mirror in the world comprises a single layer of just 200 atoms.

The Mirror of the World’s Largest Optical Telescope

The Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) is being built in the Atacama Desert, Chile. (Photo: ESO/F. Carrasco).

On a high mountain in the arid Atacama Desert of Chile, the European Southern Observatory (ESO) is constructing the world’s largest optical telescope known as the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT). The ELT is expected to start capturing images in 2028 and will enhance our understanding of the universe. However, this vision would not be possible without its cutting-edge mirrors, BBC reported on August 20.

Dr. Elise Vernet, an adaptive optics expert at ESO, has overseen the development of five gigantic mirrors: M1, M2, M3, M4, and M5. Their role is to collect and direct light to the telescope’s measurement instruments. Each mirror of the ELT is an optical design marvel. Vernet describes the convex mirror M2, with a diameter of 4.25 meters, as a piece of art, but perhaps mirrors M1 and M4 best showcase the complexity and precision involved.

The primary mirror M1 is the largest mirror ever made for an optical telescope. “It has a diameter of 39 meters and consists of 798 hexagonal mirror segments, aligned to function as a single, perfect mirror,” Vernet said. M1 will collect light 100 million times more than the human eye and can maintain its position and shape with an accuracy 10,000 times that of a human hair.

M4 is the largest deformable mirror in history, capable of changing shape 1,000 times per second to adjust for atmospheric turbulence and vibrations of the telescope—factors that can distort images. The flexible surface of the mirror is made up of six wings constructed from glass-ceramic material, each less than 2 mm thick. All five mirrors are nearing completion and will soon be transported to Chile for installation.

Scientists have created the lightest mirror in the world made from a single layer of 200 atoms. (Photo: Max Planck Institute for Quantum Optics).

The Lightest Quantum Mirror

Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Quantum Optics have developed a quantum mirror to operate at the smallest scales imaginable. In 2020, they successfully aligned a single layer of 200 atoms to reflect light, creating a mirror so small it cannot be seen with the naked eye. In 2023, they placed a micro-controlled atom at the center of the mirror, creating a “quantum switch” that controls whether the atom is transparent or reflective.

“What theorists predicted and what we observed in experiments is that in these ordered structures, when a photon is absorbed and then re-emitted, it will emit in a predictable direction. This turns it into a mirror,” said Pascal Weckesser, a postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Quantum Optics.

The ability to control the direction of the light reflected from such atoms has potential applications in various quantum technologies, such as quantum networks that are resistant to hacking for data storage and communication.

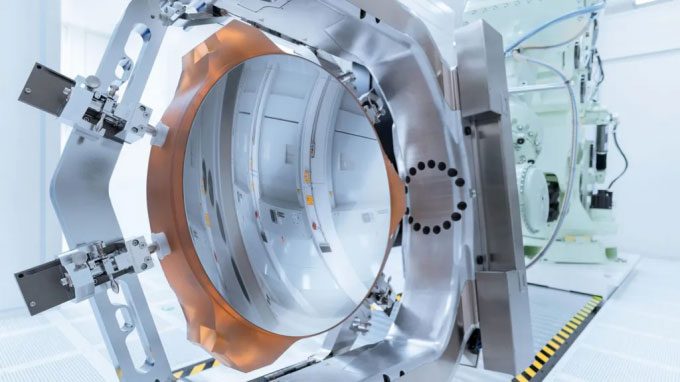

A high-precision mirror produced by Zeiss. (Photo: Zeiss).

Ultra-flat Mirrors

In Oberkochen, Germany, the optical company Zeiss is manufacturing another type of special mirror. They have spent years developing an ultra-flat mirror, which has become a key component in computer chip printing, known as extreme ultraviolet lithography (EUV).

Zeiss’s EUV mirrors can reflect light at very small wavelengths, allowing images to be rendered clearly at an extremely small scale, enabling more transistors to be printed on the same area of a silicon wafer. To explain the flatness of these mirrors, Dr. Frank Rohmund, head of the semiconductor optics department at Zeiss, uses a topographical comparison.

“If you magnified a household mirror to the size of Germany, the highest point would be 5 meters. On a space telescope mirror, like that of the James Webb Space Telescope, the highest point would be 2 centimeters. But on an EUV mirror, it’s only 0.1 millimeters,” he explained.

The ultra-flat mirror surface, combined with advanced mirror positioning control systems, delivers extremely high precision, equivalent to reflecting light from an EUV mirror on Earth to hit a golf ball on the Moon.

While these mirrors sound impressive, Zeiss plans to further improve them to create more powerful computer chips. “By 2030, the goal is to have a microchip with one trillion transistors on it. Currently, we are probably at about one hundred billion,” Rohmund shared.