The image of the Amazon rainforest often evokes a pristine wilderness, untouched by human influence. Lush green trees stretch to the horizon, brimming with unparalleled diversity of life. However, recent scientific discoveries challenge this notion, painting a picture of the Amazon as a landscape intricately shaped by human interactions over millennia.

One of the most intriguing questions arising from this new perspective is the potential role of early human activities in shaping the richness of edible plant species found in the Amazon today. While the exact number of edible plant species directly traceable to human influence from 4,500 years ago remains unknown, evidence suggests a long and complex relationship between humans and the Amazon ecosystem.

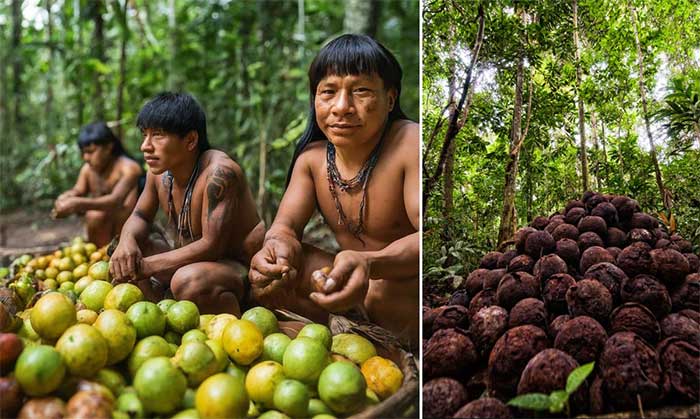

The abundance of fruits and other edible plants in the Amazon is related to ancient human activities.

A piece of the puzzle comes from a 2017 study by Levis et al., published in Science Magazine. This study explored the “lasting impacts of pre-Columbian indigenous populations on the composition of the Amazon rainforest.” It found that these populations may have engaged in activities akin to early agriculture, potentially influencing the distribution of certain plant species over time.

However, Levis et al.’s research went beyond mere presence. By analyzing the distribution and abundance of 85 tree species known to have been domesticated by pre-Columbian people throughout the Amazon basin, researchers discovered that the plants domesticated by these early inhabitants are more likely to dominate today’s Amazonian forests than other species.

Furthermore, forests near archaeological sites often exhibit higher numbers and richness of domesticated species. This strong correlation suggests a causal relationship, implying that modern Amazonian plant communities across the basin are primarily structured by historical human usage.

The Shanantina social enterprise collaborates with indigenous communities to cultivate sacha inchi, a seed native to the Amazon rainforest in Peru. It turns out that such agricultural activities have shaped the Amazon rainforest we know today for at least 4,500 years.

Diving deeper, a 2018 study by Maezumi et al., published in Nature Plants, provided a more specific view on early agricultural practices in the Amazon and their lasting impacts. The study focused on the concept of “agroforestry polyculture” (an agricultural approach involving the cultivation of multiple crops alongside existing trees), by examining remnants such as charcoal, pollen, and plant remains buried in ancient settlements and lake sediments in eastern Brazil. By piecing this evidence together, they were able to reconstruct the story of the vegetation and fire use in the region.

Their findings revealed a surprising truth: 4,500 years ago, people in the Amazon region were actively farming! Crops such as maize, sweet potatoes, cassava, and squash were cultivated to supplement their diet, and they managed to grow these crops through enriching closed-canopy forests and limited land clearing for cultivation.

Maezumi et al.’s research also highlighted an important innovation: these early farmers actively improved soil fertility to increase harvest yields. They developed a nutrient-rich soil known as Amazonian Dark Earths (ADEs), also referred to as terra preta, by adding a mixture of charcoal, bones, broken pottery, compost, and manure to the low-fertility Amazonian soil. These fertile patches of land stand in stark contrast to the typical soil of the rainforest.

Homemade biochar: charcoal composted with garden waste, kitchen scraps, and soil. The pieces of charcoal (indicated by white arrows) do not decompose during fermentation and remain in the finished compost.

Dr. Yoshi Maezumi from the University of Exeter, the lead researcher, explained the significance of ADEs: “This is a much more sustainable farming method. The development of ADEs allowed for the expansion of maize and other crop areas.” This innovation may have enhanced food security for the growing Amazon population.

Maezumi et al.’s study also underscores potential lessons for modern conservation efforts. Dr. Maezumi noted: “Ancient communities may have cleared some understory trees and weeds for farming,” but “they still maintained a closed canopy forest rich in edible plants that could provide them with food.” This stands in stark contrast to large-scale deforestation and modern industrial agriculture, which wreaks havoc on the Amazon ecosystem.

Professor Jose Iriarte from the University of Exeter emphasized the lasting legacy of these activities: “The work of the first farmers in the Amazon has left a long-lasting legacy. The way indigenous communities managed the land thousands of years ago still shapes today’s forest ecosystem.” Understanding these sustainable practices has become increasingly important as modern deforestation and climate change threaten the future of the Amazon.

The Amazon is not just a vast green land; it is also a living tapestry woven by nature and human interaction. While the exact number of edible plant species directly related to human activity remains unknown, evidence suggests a long and complex relationship.