Recently, the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism officially announced the list of national intangible cultural heritage, highlighting the significance of Hanoi Pho and Nam Dinh Pho. This news immediately captured the attention of the online community, especially food enthusiasts. Faced with these seemingly familiar dishes, many are curious about the origins of Hanoi Pho and Nam Dinh Pho.

Pho is a familiar dish of the Vietnamese people. (Photo: @peashalala).

The Origin of Pho

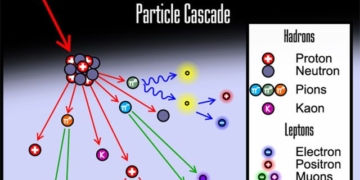

The origin of pho has been explored by many researchers who love this dish. The hypotheses vary widely. One theory suggests that the name “pho” is borrowed from the French word “feu” (meaning fire) in the term pot-au-feu (beef stew) that was introduced to Vietnam during the French colonization. However, this beef stew was traditionally cooked with various vegetables like carrots, leeks, and radishes, served with bread. Clearly, from ingredients to preparation, this dish has little in common with Vietnamese pho in terms of form or content.

French pot-au-feu dish. (Photo: Taste).

Another theory suggests that pho was invented by villagers in Nam Dinh in 1898 when the French began constructing the Nam Dinh textile factory. French technicians and thousands of workers flocked to the area to work for the largest textile factory in Indochina at that time. Some culinary-savvy locals sought to combine and improve the traditional “xao” soup, cooking it with white pho, scallions, herbs, and adjusting the seasonings to suit the tastes of diners.

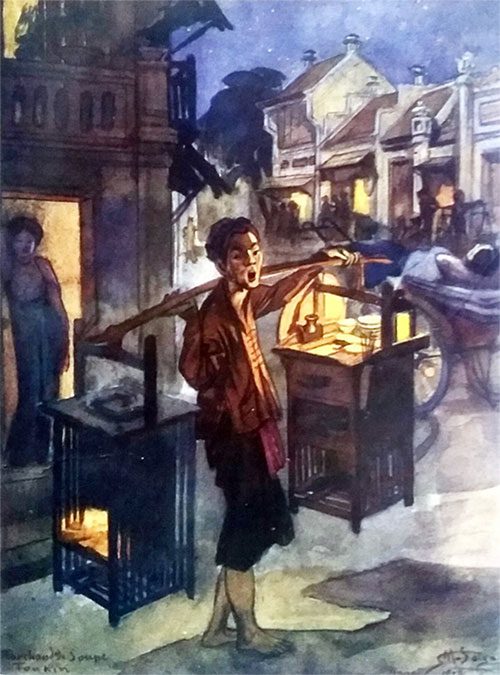

As construction workers moved from Nam Dinh to Hanoi to work on the Long Bien Bridge project, pho quickly spread beyond the village. Carrying pho stalls on their shoulders, impoverished locals followed the construction workers and soon earned a decent income selling pho, making this dish a beloved favorite among the capital’s residents.

In Hanoi, pho primarily depends on the quality of the broth.

However, these theories seem to remain just that—hypotheses. The origin of pho in Vietnam is believed to have appeared over 100 years ago, created by talented farmers who ingeniously combined simple yet refined ingredients, resulting in a uniquely Vietnamese dish. Writer and researcher Nguyen Ngoc Tien pointed out that pho evolved from a working-class meal by the riverside to a delicacy for the people of Thang Long – Hanoi, driven by the demands of the middle class, showcasing creativity and a transformation where many regional dishes became Hanoi’s specialties, thus becoming “refined” and intricate. From here, pho developed in very different directions.

For “Nam Dinh pho,” slices of beef are stir-fried with garlic and a few pieces of tomato, then placed on top of previously blanched pho noodles before the chef pours a fragrant broth into the bowl. In contrast, the Hanoi approach to the dish is more minimalist. In Hanoi, pho primarily relies on the quality of the broth, creating a sensation that even the herbs can overshadow the flavor of the pho.

Illustration of a pho stall.

Speaking of pho, writer Thach Lam described it in the book “Hanoi’s Thirty-Six Streets”: “Pho is a special gift of Hanoi, not only found in Hanoi, but it is precisely because it is only in Hanoi that it is delicious.” He evaluated that “Delicious pho must be ‘classic’ pho, made with beef, with clear and sweet broth, chewy noodles that are not mushy, tender fatty brisket, and garnished with lime, chilies, and onions,” along with “fresh herbs, black pepper, a tangy drop of lime, and a touch of shrimp paste, lightly scenting like a suspicion.”

By the 1940s, pho had become very popular in Hanoi, a meal enjoyed throughout the day by all strata, especially civil servants and laborers. People could eat pho at any time—breakfast, lunch, or dinner. Pho has accompanied the ups and downs of the lives of people in Hanoi for over a century. Over time and through various circumstances, pho has spread to many regions. From rural villages to urban areas, in the homeland or alongside Vietnamese people traveling across the globe. From times of hardship and social upheaval to moments of peace and prosperity, pho remains a staple in daily life, enjoyed by people of all ages and even becoming a favorite dish for many diners.

People can eat pho all day, at breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

The Century-Long Journey of Pho

The century-long journey of pho has been summarized by the elders of the pho community as follows: In the early years from 1908 to 1930, pho appeared and took shape; from 1930 to 1954, pho developed and reached its peak; from 1954 to 2000, it recorded a tumultuous period, giving pho a vibrant appearance. Entering the 21st century, pho can be considered to have officially marked a period of integration, globalization, and industrialization.

This dish has transcended the borders of Vietnam to reach many countries worldwide.

Since September 2007, pho has been officially included in the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, published on September 20 in the UK and the US. Pho has officially become a proper noun in this prestigious English dictionary, contributing to the recognition of Vietnamese cuisine on the global culinary map.

Since 2011, along with spring rolls, Vietnamese pho has been ranked by CNN among the 50 best dishes in the world.

Since 2017 in Vietnam, December 12 has been designated as Pho Day, becoming an annual traditional activity aimed at promoting tourism and community culture. In 2019, pho was listed among the top 10 best dishes in the world by CNN.

On August 23, 2022, banh mi, pho, and Vietnamese coffee were ranked among the top 50 street foods in Asia by CNN…

Now both Hanoi Pho and Nam Dinh Pho have been honored as national intangible cultural heritage in 2024.

Foreign tourists enjoying pho. (Photo: Nam Nguyen, Khieu Minh).

From its inception to the future, pho will undoubtedly hold a significant place in the menu of the Vietnamese people. If anyone wonders why Vietnamese people love pho so much, it may be due to Vietnam’s hot and humid climate, making soupy dishes like pho fulfill this need. Moreover, pho suits Vietnamese tastes as it is a dish skillfully prepared from rice, bones, meat, various herbs, and spices. There are many bustling pho shops in Hanoi, each with a secret recipe, attracting different numbers of customers with unique preferences.

In Nam Dinh, there are villages specializing in pho production, such as Van Cu and Giao Cu, where many people have passed down the craft from generation to generation, spreading the art of pho both domestically and internationally. Saying pho is the “national soul” of Vietnam is not an exaggeration; it remains both a popular dish and a specialty deeply rooted in the traditional cultural identity of the Vietnamese people.