In June 1798, British chemist and physicist Henry Cavendish successfully calculated the mass of the Earth through an experiment measuring the gravitational constant (G). This experiment is known in the scientific community as the Cavendish Experiment or Earth Balance Experiment.

Henry Cavendish (1731 – 1810) was a rather shy and eccentric scientist. He typically wore clothing that was about 50 years out of fashion. He disliked socializing with strangers, especially women. To avoid being seen by his neighbors, he often took walks at night and even built an extra staircase in his house to avoid encountering the servants on the main staircase.

Contrary to his peculiar personality, Cavendish was a great scientist. He had the ability to conduct experiments and measurements with extreme precision, a skill not suited for the impatient. He enjoyed creating and repairing scientific instruments and constantly sought to improve them. He worked meticulously, never feeling satisfied once a task was completed.

Like many scientists of his time, Cavendish was born into an aristocratic family, allowing him to inherit a substantial fortune to comfortably conduct chemical and physical experiments. He transformed most of his home into a laboratory, reserving only a small part for living space.

Among his research projects, the most notable was the experiment that helped him determine the mass of the Earth. This experiment is now referred to as the “Cavendish Experiment.”

Isaac Newton published the law of universal gravitation in 1687, but he made no effort to determine the gravitational constant (G) or the mass of the Earth. By the 1700s, astronomers sought to determine the mass of the Earth to calculate the masses of other planets in the solar system. Additionally, as America was newly discovered and colonized, cartographers needed to know the size and mass of the Earth. In 1763, English surveyors Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon were hired to survey and determine the boundary between the two colonies of Maryland and Pennsylvania in North America. Cavendish examined the accuracy of Mason and Dixon’s measurements. He noted that the Allegheny Mountains exerted a slight pull on their surveying equipment due to gravitational attraction. This could affect the measurements, but he was not aware of the extent of this influence.

In 1772, the Royal Society of Great Britain established a committee to measure the mass of the Earth. In the field of physics, knowing the gravitational constant (G) allows us to easily calculate the mass of the Earth using the following formula: M = gR²/G (where: M is the mass of the Earth, g is the gravitational acceleration at the Earth’s surface equal to 9.8 m/s², and R is the Earth’s radius equal to 6,384 km). To find the Earth’s density, one simply divides the mass of the Earth by its volume.

The question arose: how to accurately determine the value of the gravitational constant (G). Many proposed the idea of finding a mountain with a symmetrical shape and measuring how much it deflected a plumb line [a small weight attached to a string]. The mountain’s effect on the plumb line is minimal due to the weak gravitational force. The committee members conducted experiments using a large mountain in Scotland. After measuring the angle of deflection, they easily calculated the value of G and inferred the Earth’s density to be 4.5 times that of water. However, Cavendish believed this experiment was prone to error and that the results obtained were not accurate.

The experiment to determine the gravitational constant (G) based on measuring gravitational force between objects in a laboratory was first proposed by geologist Reverend John Michell, who created a torsion balance to accurately measure small torque but passed away in 1793 before he could conduct his experiment. The torsion balance was later passed to Francis John Hyde Wollaston and then to Cavendish.

Cavendish contemplated Michell’s method of measurement for a long time. By 1797, he began conducting his own experiments. He found that Michell’s setup was not sufficiently accurate for measuring the gravitational force between two small metal spheres and sought to improve it.

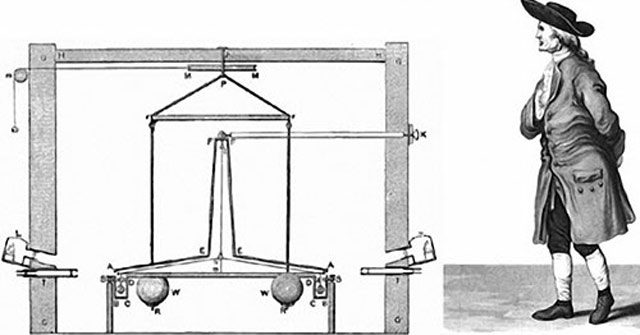

Cavendish attached two metal balls to either end of a 1.8-meter long wooden rod. He suspended the entire system with a thin wire, keeping the rod horizontal. Then, he moved two lead spheres, each weighing 159 kg, close to the two balls at the ends of the rod. To avoid experimental errors caused by wind, he placed the system in a windless room and observed it using a telescope through a window. The room was also kept dark to avoid temperature discrepancies in different parts of the room, which could affect the results of the experiment.

The gravitational force exerted by the two lead spheres on the two balls caused the wooden rod to rotate slightly. Cavendish measured this angle using the telescope and calculated the torque acting on the torsion wire, from which he determined the gravitational constant based on the mass of the lead spheres and the balls.

After determining the value of the gravitational constant (G) and gravitational acceleration (g) at the Earth’s surface, Cavendish calculated the mass of the Earth to be 6×10²⁴ kg. He detailed the results of his experiment in a 57-page paper published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of Great Britain in June 1798. This result led to another name for Cavendish’s experiment: the Earth Balance Experiment. The measurement of the Earth’s mass also allowed for the inference of the mass of the Moon and other celestial bodies in the solar system through the laws of mechanics and the law of universal gravitation.

The Cavendish Experiment was the first to accurately measure the gravitational constant (G), based on the principle of measuring the gravitational force between two masses. Many other scientists repeated Cavendish’s measurements, but none proposed any improvements over the experiment he established.

Today, instructors often have physics students replicate Cavendish’s experiment when they want to measure the value of G. The name Cavendish has been used to designate the Henry Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge, one of the most modern research laboratories in the UK.

|

More on the Cavendish Experiment The apparatus designed by Cavendish was a torsion balance made from a 1.8 m long wooden rod suspended horizontally by a string, with two lead spheres of 51 mm diameter and weighing 0.73 kg attached to each end. Then there were two other lead spheres, each with a diameter of 300 mm and weighing 158 kg, placed near the smaller spheres, spaced 225 mm apart and secured by a separate support system. Accordingly, this experiment would measure the weak gravitational attraction between the small and larger spheres. The two larger spheres were placed on alternating sides of the horizontal arm of the balance. Their mutual attraction to the smaller spheres caused the arm to rotate and twist the supporting wire. The arm stopped rotating when it reached an angle where the twisting force of the wire balanced the net gravitational force between the two larger and smaller lead spheres. By measuring the angle of the wooden rod and knowing the twisting force (torque) of the wire at a specific angle, Cavendish was able to determine the force between the pairs of masses. Since the gravitational force of the Earth acting on the small sphere could be directly measured by weighing it, the ratio of the two forces allowed for the calculation of the Earth’s density using Newton’s law of universal gravitation. |