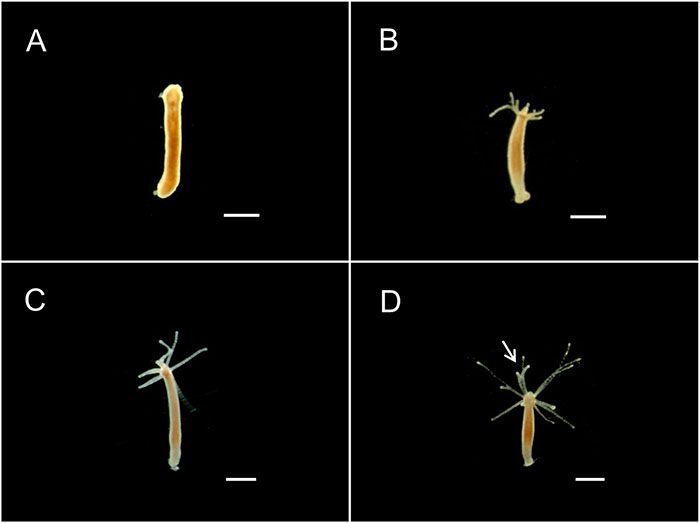

In the oceanic world, some species possess strange and wonderful abilities that humans cannot attain. For instance, the immortal jellyfish – Turritopsis nutricula, which is the only known multicellular organism that can reverse its life cycle from the mature stage back to its single-celled polyp stage. Another example is Hydra magnipapillata, a species of invertebrate that can regenerate. When a Hydra is cut into multiple pieces, each piece can grow back into a complete new individual.

The regenerative characteristics of these organisms have drawn the interest of biologists in their quest for evidence of immortality in nature. Why do these species seem to have limitless life, completely free from the constraints faced by other organisms?

Hydra magnipapillata, a species of invertebrate that can regenerate.

It is important to note that the concept of immortality referred to in this article is biological immortality. Biological immortality means that we are considering aging in terms of the activities occurring within the organism’s body that are not affected by aging or malfunctions due to old age. However, they can still die from accidents, physical impacts, malnutrition, etc.

The concept of aging was described in the mid-20th century as a trade-off between reproduction and cellular maintenance. Initially, the bodies of organisms utilize resources and focus on growth and maintaining health. During childhood and adolescence, the focus is on making the organism as strong as possible. Once the reproductive organs are fully developed, that priority gradually shifts towards reproduction. For most organisms, the resources within their bodies are limited, and diverting those resources to produce offspring must come at the cost of their health.

Salmon swimming upstream to spawn.

For example, a salmon that swims upstream to spawn may die shortly after. Everything seems to be utilized solely to create the best opportunity for the salmon to reach its spawning grounds. The act of making a return trip downstream, surviving for another year at sea, and then returning upstream to spawn is extremely rare. This is a far-fetched scenario, and natural selection usually does not favor it. In most cases, this success only occurs once in their lifetime.

When organisms reach the appropriate age for reproduction, the aging process begins, ultimately leading to death. Alexei Maklakov, an evolutionary biologist and gerontologist at the University of East Anglia in the UK, points out that this is not necessarily to make way for the next generation. Throughout life, human genes continually accumulate mutations, some of which are entirely random, while others are a result of diet and other external factors. Most of these mutations do not affect or are harmful to the body.

Gabriella Kountourides, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Oxford, states: “Any gene mutation that reduces reproductive capacity or harms the organism’s fitness before reproduction will be strongly resisted. However, once the organism reaches sexual maturity, the point at which it can pass on its genes to the next generation, its ability to resist natural selection weakens.“

When swimming upstream to spawn, the salmon has successfully matured to reproductive age.

Take the case of a salmon swimming upstream to spawn. The animal has successfully matured to reproductive age. If a gene mutation occurs in the fish that makes it stronger and able to live for another year after spawning, those fish would not have a significant advantage over others.

From a natural selection standpoint, there is little benefit in continuing to strive for health after reproduction. “An individual may want to survive, but at that point, natural selection is not going to work hard because it does not offer any benefits for the next generation,” she adds.

However, not all species are as extreme as salmon. Some species can continue to live to have more offspring throughout their lifetime, such as humans. Most mutations in human DNA will have negative effects or no effect at all. Our bodies can repair some of this DNA damage, but that ability diminishes with age.

“Eventually, aged cells can accumulate in tissues, causing damage and inflammation, and are also precursors to age-related diseases. Aging and death can occur in two ways. The first is the accumulation of negative mutations due to weak selection, which can provide reproductive benefits but harm long-term survival.” For example, the BRCA gene mutation, known for significantly increasing the risk of breast and ovarian cancer, is also associated with high reproductive capability in those carrying the mutation.

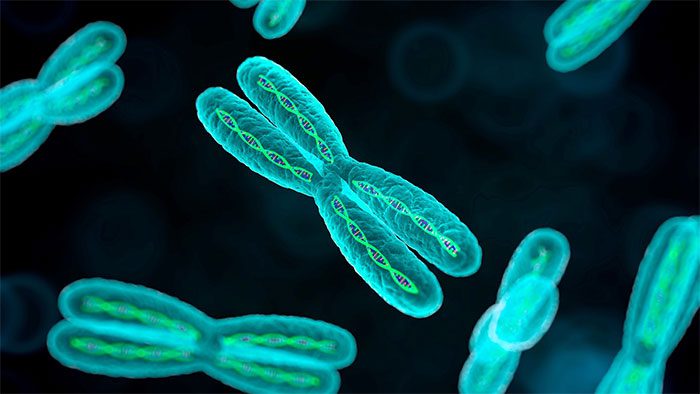

Each time a cell divides, chromosomes lose small amounts of DNA from the telomere.

The second way is through cellular aging, a phenomenon where cells become limited in their ability to divide. In mammals, chromosomes have protective ends. In humans, telomere repeat sequences range from 5,000 to 15,000 bases. Each time a cell divides, chromosomes lose small amounts of telomere DNA, about 50-100 bases. Eventually, when telomeres are depleted, cells can no longer divide. They age and accumulate in tissues, causing damage and inflammation, and are also signs of age-related diseases.

Although most species age over time, some exceptions still exist. For example, many plant species have shown “negligible senescence,” with some known to have lived for thousands of years. One such case is the Pando tree in Fishlake National Forest in Utah. It spans over 400,000 square meters and weighs over 6,000 tons. Estimates suggest that this population of trees may be over 10,000 years old.

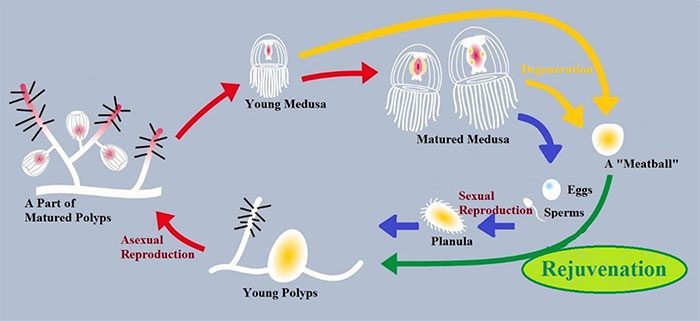

Another example is the immortal jellyfish, a species belonging to the class Hydrozoa, which has two developmental stages in its life cycle: the polyp stage and the medusa stage. In this case, mature jellyfish can reverse their life cycle from the adult stage to the polyp stage if they are injured, ill, or threatened.