A study finds that trees also dislike inhaling smoke from wildfires. They choose to “hold their breath” and stop photosynthesis.

A team of atmospheric and chemical scientists at Colorado State University (USA) has been investigating air quality, the ecological impact of wildfire smoke, and other pollutants.

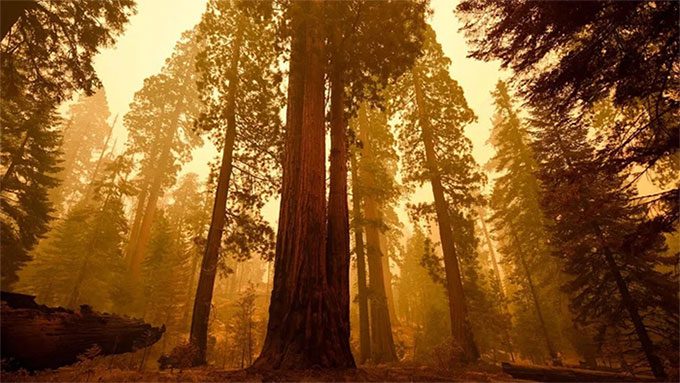

Trees cannot escape wildfire smoke – (Photo: Getty Images)

They explored how plants release volatile compounds—chemicals that give forests their characteristic smell but also affect air quality.

The research began somewhat serendipitously when smoke from a wildfire engulfed the team’s research site in Colorado, allowing them to observe in real-time how leaves reacted to smoke, according to LiveScience on July 31.

Trees have pores called stomata on the surface of their leaves. When wildfire smoke drifts away, it undergoes chemical changes under sunlight.

A mix of volatile organic compounds, nitrogen oxides, and sunlight creates ground-level ozone, which can lead to respiratory issues in humans. This mixture also harms trees by degrading leaf surfaces, oxidizing plant tissue, and slowing down photosynthesis.

The fall of 2020 was a devastating wildfire season in the western United States, and thick smoke enveloped a field site for the research team in the Rocky Mountains, Colorado.

On the first morning covered by dense smoke, the team conducted routine tests to measure the photosynthesis of Ponderosa pine leaves. They were surprised to find that the tree’s stomata were completely closed and photosynthesis was nearly zero.

A clear day vs. a day affected by wildfire smoke (right) in tests in Colorado, USA – (Photo: Mj Riches).

The team also measured the emission of volatile organic compounds from the leaves and found it to be very low. This meant that the leaves were “not breathing”: They were not taking in the necessary CO2 for growth and were not releasing the chemicals they typically emit.

The team decided to try “forcing” the trees to photosynthesize by cleaning the “breathing pathways” of the leaves, altering temperature and humidity. They found that photosynthesis improved alongside the emission of volatile organic compounds.

Data collected over several months confirmed that some plant species respond to thick wildfire smoke by “holding their breath.”

The team proposed hypotheses that could explain why the stomata close, including the possibility that smoke particles cover the leaf surfaces, preventing the stomata from opening, or that smoke could enter the leaves and clog the stomata, or that the leaves might physically react to the initial signs of smoke and close the stomata before being severely affected. It is likely a combination of these reactions and others.

The team has yet to draw definitive conclusions about the duration of the effects of wildfire smoke on plants, including trees and crops, especially if wildfires persist and smoke lingers for several days.