The young cave lion named Sparta looks like it has been sleeping for thousands of years beneath layers of permafrost in Siberia.

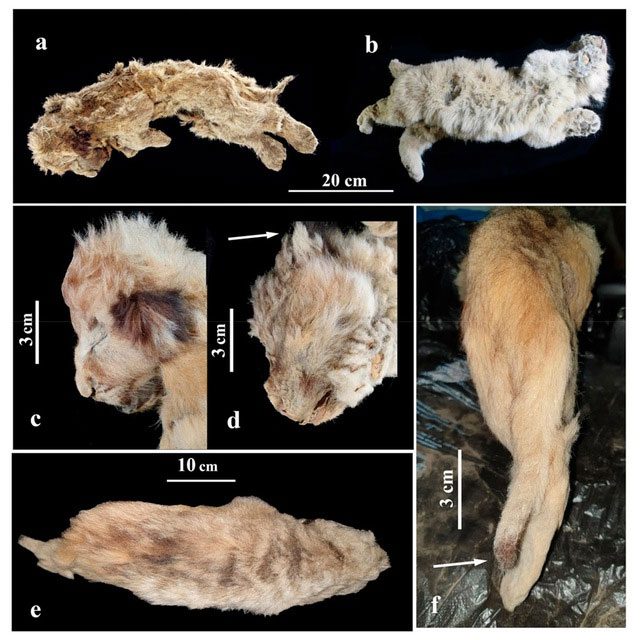

The golden fur of the young female lion is muddy but undamaged. Although its teeth, skin, soft tissue, and internal organs have become mummified, everything remains intact. About 28,000 years after the animal closed its eyes for the last time, its teeth are still sharp enough to pierce the hand of one of the scientists studying the specimen preserved under the permafrost.

Sparta is one of two young cave lions, a now-extinct big cat species that once roamed widely across the Northern Hemisphere, discovered by mammoth ivory hunters along the Semyuelyakh River in the Russian Far East in 2017 and 2018.

The intact mummy of the young lion Sparta. (Photo: Love Dalen).

The Importance of Prehistoric Creatures

Prehistoric creatures preserved in the permafrost are not only witnesses of the past but also provide invaluable information for modern science. They allow researchers to understand the living conditions, habits, and evolution of species in the past. From this, we can infer how prehistoric beings adapted and survived in harsh environments.

Studying the DNA from prehistoric specimens like Sparta helps scientists gain a better understanding of biological evolution. This not only expands knowledge about natural history but also provides useful information for studying and predicting environmental changes in the future. These insights can be applied to develop more effective conservation strategies and environmental management.

Initially, researchers thought the two lions were siblings because they were found only 15 meters apart. However, new studies reveal they are 15,000 years apart in age. According to radiocarbon dating, the second lion, named Boris, is 43,448 years old. “Sparta may be the best-preserved Ice Age animal, almost entirely intact except for slightly tangled fur. It even has its whiskers intact. Boris is a bit more damaged but still in good condition,” said Love Dalen, a professor of evolutionary genetics at the Centre for Paleogenetics in Stockholm, Sweden, and the author of the new study.

Both lions were just 1-2 months old when they died. Experts are unclear how they died, but Dalen and colleagues from Russia and Japan noted there are no signs that they were killed by predators. CT scans reveal skull damage, rib fractures, and other deformities in their skeletons. Based on their preservation state, the two lions were likely buried very quickly. Therefore, they may have died in a landslide or fallen into a crack in the permafrost. Such ground typically forms large cracks due to seasonal melting and freezing.

During the last Ice Age, Siberia was not barren as it is today. Mammoths, Arctic wolves, woolly rhinoceroses, bison, and saiga antelopes roamed alongside cave lions, which are larger relatives of the modern Asian lions. Researchers are still uncertain how cave lions survived in harsh environments with strong winds and dark, cold winters. A study published in the journal Quaternary found that the fur of cave lions has a similar but not identical structure to that of Asian lions. The thick, long fur allowed them to adapt to the cold climate.

The research team needs to examine infectious diseases like anthrax in the frozen cave lion remains before considering further details, although Dalen believes they are unlikely to carry ancient pathogens. The gender of the two young lions was confirmed through CT scans and genetics. The next step is to sequence Sparta’s DNA to explore the evolutionary history of cave lions, their population size, and unique genetic traits.

Scientists need to plan for the survey and conservation of these specimens.

The Threat of Ancient Viruses

Another serious issue is the release of ancient viruses as permafrost melts. These viruses have been buried in ice for thousands of years, and humans do not yet have the capability to identify and control them. If these viruses are released into the environment and infiltrate human communities, they could cause new outbreaks that we are ill-equipped to combat.

These ancient viruses may pose not only a threat to humans but also to modern animals and plants. We have witnessed the devastating power of pandemics throughout history, and facing viruses that we have never encountered before could present an enormous challenge.

To address these challenges, urgent and comprehensive measures are needed to mitigate the impacts of climate change. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions is one of the most critical steps to prevent the melting of permafrost. Governments and international organizations must collaborate to develop more effective environmental protection technologies and policies.

Additionally, prioritizing the research and monitoring of prehistoric organisms preserved in permafrost is essential. Scientists need to plan for the survey and conservation of these specimens before they completely melt away. This will not only help protect valuable biological heritage but also provide crucial information for scientific research and responses to climate change.

The discovery of the young lion Sparta in the permafrost is a clear testament to the remarkable preservation capabilities of this ice. However, the melting of permafrost due to climate change poses many challenges and potential risks. To protect our planet and maintain valuable biological heritage, specific and decisive actions from the international community are required to mitigate the impacts of climate change and conserve natural habitats.

Only when we are fully aware and act promptly can we protect our planet and ensure that the stories of Sparta and other prehistoric creatures are not just warnings from the past, but also motivations for us to build a more sustainable future.