In 430 BC, during the Peloponnesian War in ancient Greece, the people of Athens were struck by a mysterious disease, resulting in horrific consequences that still send chills down the spine when reading the accounts of historians today.

|

|

Greek historian Thucydides |

Historian Thucydides survived the deadly pandemic and left vivid descriptions of its symptoms.

“A healthy person suddenly feels dizzy as if struck by a strong wave of heat from the top of the head, as if there is fire burning in the eyes, in the body, in the throat and tongue, exhaling an unusual and foul smell,” Thucydides wrote.

But that was just the beginning – next came sneezing, coughing, followed by diarrhea, vomiting, and cramps. Subsequently, the skin of the patients turned a grayish-green, developed sores and ulcerations, and they suffered from an intense thirst. Most patients died around the 7th or 8th day of illness due to abscesses damaging the intestines, diarrhea combined with exhaustion. A few survivors were left with lasting effects – missing fingers and toes, genital mutilation, and blindness. Others lost all memory; they did not know who they were and could not recognize their friends.

This is the first recorded account of a pandemic in the world.

Thucydides indicated that this disease originated from Ethiopia, spread to Egypt and Libya, and then reached the lands of Greece. Within four years, it killed one-third of the population and army of Athens, including this ancient city’s leader.

Therefore, it may not be surprising why the term “pandemic” originates from the Greek language, where “pan” means “all” and “demos” means “people.”

In the 2nd century AD, the power of European dynasties overshadowed Rome, partly due to their expeditionary armies. However, in 165, after returning from an Eastern campaign, these troops brought back a disease that killed about 5 million people.

This killer was named the Antonine Plague, named after one of the two Roman emperors, Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (who died from this disease). It killed a quarter of those infected.

This killer was named the Antonine Plague, named after one of the two Roman emperors, Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (who died from this disease). It killed a quarter of those infected.

In 166, the Greek physician Galen, on his way from Rome to what is now Turkey, recorded some symptoms of the killer. He described the disease as causing fevers, diarrhea, and a burning sensation in the throat, along with dry skin or skin eruptions. Later scholars concluded that the pandemic at the time was likely smallpox.

Another outbreak of smallpox occurred between 251 and 266, peaking at killing 5,000 people daily in Rome.

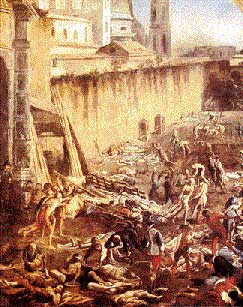

But these horrendous figures pale in comparison to a disaster in the 6th century when another killer attacked the city of Constantinople (now Istanbul) during the reign of Byzantine Emperor Justinian I.

The plague is believed to have originated in Ethiopia or Egypt and spread northward through grain-carrying merchant ships. It was transmitted by fleas living on rats that infested the ships. This was the first recorded pandemic of the plague in history.

Within two years, the plague killed 40% of Constantinople’s population. Byzantine historian Procopius recorded that at its peak, the plague death took 10,000 lives daily in the city.

The plague spread throughout the eastern Mediterranean, resulting in a quarter of the region’s population perishing.

The plague spread throughout the eastern Mediterranean, resulting in a quarter of the region’s population perishing.

The second plague pandemic erupted in 588, with even more horrifying effects, reaching as far as France. The death toll from this killer reached 25 million.

In the following 800 years, Europe was free from any pandemics, but by the mid-14th century, the plague returned. This time it was dubbed the Black Death. The name derived from the fact that the skin of those infected turned darker due to black spots under the skin, resembling the symptoms of those unfortunate individuals eight centuries earlier.

People fled to escape the disease, but this only caused it to spread further across the continent. In three years from 1347, the Black Death killed about a quarter of Europe’s population – 25 million people. During the same period, the plague ravaged Asia and the Middle East, leading to a global pandemic.

The plague erupted multiple times in Europe, each time more severe than the last, and only subsided when humanity entered the 18th century. By then, the total number of victims recorded from this disease stood at approximately 137 million. Urban areas suffered the most, with losses of about 50% of the population in each pandemic.

Cholera, first noted by Portuguese physician Garcia de Orta in the 16th century, only became a global pandemic in 1816.

That year, the disease raged in India, then followed trade routes into Russia and Eastern Europe before spilling into Western Europe and North America.

The world has battled at least seven cholera pandemics, six of which occurred in the 19th century, affecting all continents except Antarctica. The most recent outbreak was in 1961 in Indonesia, but due to improved sanitary conditions, its lethality has significantly decreased. Cholera remains one of the silent killers to this day.

If the 19th century was the era of cholera, the following 100 years became the age of influenza, with three major pandemics.

If the 19th century was the era of cholera, the following 100 years became the age of influenza, with three major pandemics.

The deadliest and most widespread influenza pandemic was the Spanish flu, which emerged in 1918 with three major outbreaks in France, the USA, and Sierra Leone. This disease had an extraordinarily high mortality rate, often killing those aged 20-40, while appearing to “spare” the elderly and very young.

The Spanish flu spread at a terrifying speed, killing 25 million people within six months, with one-fifth of the world’s population infected.

This killer vanished as quickly as it appeared, but it left behind approximately 40 million corpses, more than the number of deaths in World War I.

T. Huyền (according to BBC)