British Scientists Uncover Why Some Giant Planets Drift Towards Their Host Stars

A recent study published in the scientific journal The Astrophysical Journal Letters has discovered a new mechanism that may explain the long-standing mystery of the decaying orbits of certain planets around sun-like stars.

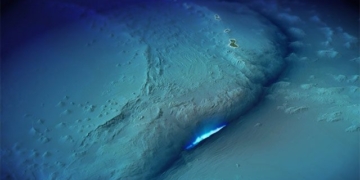

A hot Jupiter falling into the red-hot zone of its host star – (AI Image: Anh Thư)

According to SciTech Daily, scientists have previously observed the moth-like behavior of some exoplanets classified as “Hot Jupiters.”

These gas giants, similar to Jupiter, orbit extremely close to their host stars, resulting in extreme temperatures. They take just a few days to complete an orbit around the star, always appearing as if they are about to be swallowed.

This close proximity subjects both the planet and the star to strong gravitational forces, transferring energy into their orbits.

However, these planets do not get swallowed immediately; instead, they slowly spiral inward over billions of years until they eventually fall into the red-hot zone of their host stars.

Current tidal theories cannot fully explain the peculiar orbital decay mentioned, such as that of the hot Jupiter WASP-12b in the WASP-12 system.

In astronomy, tidal force is a gravitational effect that stretches an object closer to or away from a massive body due to the difference in gravitational fields.

The research team led by Durham University (UK) discovered that a strong magnetic field within some sun-like stars can effectively dissipate the tidal forces from hot Jupiters.

Tidal forces create waves that move inward within the stars. When these waves encounter a magnetic field, they are converted into various types of magnetic waves that radiate outward and eventually dissipate.

Thus, with only the influence of the star instead of mutual gravitation, the planets undergo a very slow weakening of their orbits.

They move in a spiral pattern, gradually getting closer without plunging directly into their host star, nor maintaining a stable position.

Dr. Craig Duguid, the lead author of the study, stated that this new mechanism has profound implications for the existence of short-period planets, particularly hot Jupiters.

It opens up a new avenue for tidal research and will help guide astronomers in their observations to identify promising targets for studying orbital decay.