While it is generally accepted that rockets were invented in China, the exact timeline and conditions of their invention remain uncertain. This is not due to a lack of written evidence, but rather because it is difficult to ascertain whether historical chronicles and documents from that era refer to tools for launching fire, which carried combustible materials but were propelled by bows, crossbows, or other machinery, or whether they indeed refer to rockets propelled by gas ejection from explosives.

The Development History of Rockets

Indeed, it has been established that the rockets mentioned in the oldest texts actually refer to arrows carrying combustible substances. Based on completely authentic evidence, it seems that fireworks in the form of rockets, the first application of gunpowder propulsion, became a popular folk activity in China during the Tang Dynasty (618-907).

The use of this very propulsion to launch projectiles at enemies is confirmed by numerous accounts of battles fought by the Chinese against the Mongols in the 13th century. Specifically, during their siege of the capital city of Kaifeng, the Chinese successfully used small rocket-propelled projectiles, which were bamboo tubes filled with gunpowder, attached near the pointed tip, with an opening facing where the rocket tail would be mounted.

It was the Mongols who spread rocket technology widely during their campaigns. Notably, they used them near Budapest in 1241 and later in Baghdad in 1251.

However, it was primarily through the Arabs that Europeans became acquainted with gunpowder and rockets. Although Albertus Magnus provided the formula for making “flying fire” in his book “On the Wonders of the World“, it was thanks to Marcus Graecus or Marc le Grec (Marc the Greek) that we have a detailed description of rockets in his book on the fires to burn enemies. This book likely appeared between 1225 and 1250 or 1270. We also note that among the pioneers of rocket technology in the Middle Ages, the Italian Muratori used the term rochetta in 1379, which was later transformed into roquette in French and then into rocket in English.

For many centuries, rockets did not advance. Empirical approaches dominated the manufacturing of the shells, where the gunpowder served as a propellant, resulting in poor performance.

From the late 17th century, to serve as the centerpiece of fireworks displays, stronger rockets were used to carry payloads high, primarily flags and other small items, which would sequentially fall to the ground after being launched into the air. In some cases, there were plans to attach a small animal to them, to drop it – oh, how horrifying – dangling from a rudimentary parachute.

In 1804, British officer William Congreve returned from India, where he had suffered deadly attacks from the rockets of Tippoo Sahib, the last Muslim king of Mysore. He successfully persuaded the British government to assign him the task that would lead to the first rational study of military rockets. He perfected a model weighing 15 kg, with a range of 2500 to 3000 meters, and subsequently, two thousand versions were launched at the city of Boulogne starting in 1806. Immediately, other powers became interested in this weapon they had used sporadically in the past, and many advancements were achieved almost everywhere. However, by the mid-19th century, gunpowder war rockets were replaced by cannonballs.

In 1898, the long history of rockets filled with ups and downs reached a decisive turning point. An anonymous Russian teacher, Constantin Tsiolkovsky, laid the scientific foundation for the field of space travel based on the use of liquid-fueled rocket propulsion. His contributions were even more significant because the liquids he proposed in 1903 were hydrogen and liquid oxygen, which remain the fuels (or propellants) for the most advanced rockets today.

At that time, it was still too early for authorities and private companies to take an interest in rockets. The authorities themselves considered the era of those tools to be over. Thus, for a third of the 20th century, research on these tools remained the enthusiastic, often unprofitable work of a few isolated pioneers. For thirty years, Tsiolkovsky provided a substantial theoretical body of work. In France, from 1912, Robert Ernault Pelterie, in an article titled Observations on the Results of a Method to Reduce Engine Weight, discussed using rockets to launch spacecraft.

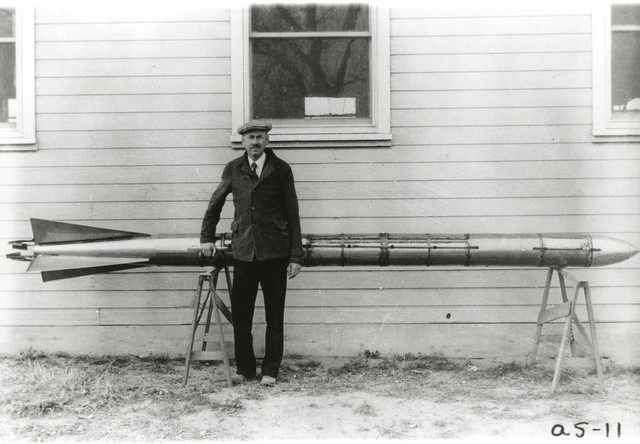

Inventor Robert H. Goddard with the first liquid-fueled rocket in the world.

Inventor Robert H. Goddard with the first liquid-fueled rocket in the world.

During this period, a young American physics professor, Robert H. Goddard, began his extraordinary career as a solitary researcher. His first experiments with gunpowder rockets were conducted in 1915. He then worked for the U.S. military, but when the armistice was declared, the military lost interest in his work. Thus, Goddard had to conduct personal research.

In 1919, he published a classic book on rocket technology: Methods for Achieving Extremely High Altitudes. In 1923, he aligned his research with Tsiolkovsky’s views and focused on liquid-fueled rockets. Three years later, he successfully accomplished the first brief flight of a small rocket, launched with a mixture of kerosene and liquid oxygen, reaching a height of 30 meters. Despite the indifference of government agencies, policymakers, and the most serious industrialists, Goddard persevered in his courageous career, and just before World War II, his rockets – which included all components of future space launch systems – reached altitudes of 2200 meters and speeds of 1000 km/h.

Germany also had its own solitary rocket scientist, Hermann Oberth, who published a work titled “Rockets to Space Between Planets” in 1923. He also needed assistance, and in 1928, became a technical advisor for the film A Woman on the Moon by Fritz Lang, which required the filmmaker to provide the necessary funding to develop a real rocket using liquid propellant, intended to be launched when the film was released. This launch did not materialize because Oberth was more of a theorist than a practitioner and could not complete the project by the desired deadline, but the incident had a positive effect in generating significant interest among German youth for the space travel movement. Around Oberth, a group of young engineers quickly gathered, among whom Wernher von Braun stood out.

A similar enthusiasm stirred many young people in Russia to compete with Tsiolkovsky. In the late 1920s, the key figures in the movement were Fridrikh A. Tsander, who built the first liquid-fueled rockets in 1930, and Valentin P. Glushko, who developed many large rockets from 1930 onwards. Some of these rockets were later used to propel an aircraft – a rocket designed by Sergei Korolev, an engineer with a promising future, but who was not heard from before his death. Indeed, war was approaching, and research focused on refining military equipment shrouded in secrecy.

More is known about what happened in Germany. Amateur researchers of VfR (Verein für Raumfahrt, Space Flight Society), after using rockets to propel cars – thus promoting both their mission and Opel – by 1930 began experimenting with small liquid-fueled rockets. However, the enthusiasm of the society was dampened by the economic crisis, and in 1932, the leaders had to seek military assistance. It was after a demonstration organized for military experts that they recognized the potential of liquid-fueled rockets as a means to transport offensive weapons. According to Von Braun himself, at that time he was invited by General W. Domberger to join the research center led by the general “to provide him with experimental means for his doctoral thesis on new rockets.“

In 1936, the green light was given to General Domberger, who established a renowned military research facility on the central Baltic coast at Peenemünde, with Wernher von Braun taking on the technical leadership. As the fortunes of the German armed forces turned unfavorable, Hitler belatedly recognized the importance of long-range missiles. Massive resources were allocated to Domberger, and at one point, up to 20,000 people were employed at Peenemünde or supporting its operations. As a result, on October 3, 1942, the first experimental A-a missile was launched. By September 8, 1944, a 15-ton device, carrying one ton of explosives, known as the V2, was operational and had been launched towards London and Paris.

At the end of the war, Von Braun and several members of his team escaped Peenemünde before the Russian forces arrived, bringing with them a cache of V2 rockets to the United States. It was with these individuals and equipment that the U.S. began its efforts in intercontinental weapons and space research. The progenitor of the large, multi-stage rockets currently launched from the Kennedy Space Center is the V2, which was equipped with a Wac-Corporal small rocket. This device, launched on February 24, 1949, reached an altitude of 403 km. The first rocket built by Von Braun’s team was a Redstone rocket weighing 20,400 kg. From this V2-derived device, the Jupiter rocket was developed, weighing 47,600 kg and consuming kerosene and liquid oxygen. It was with the Jupiter that the Americans successfully launched their first satellite on February 1, 1958.

Three months earlier, public opinion and experts alike were astonished by the launch of the Russian Sputnik, weighing 84 kg, followed by another satellite weighing 508 kg just a month later. Clearly, in the Soviet Union, confidence was also placed in rocket scientists, with long-standing research conducted there under state sponsorship and in complete secrecy. For instance, it wasn’t until 1966, during the state funeral for Serge Korolev—who had been unheard of since the 1930s—that it was revealed he was the father of the Soviet space rockets.

Shortly thereafter, increasingly powerful and reliable rockets were developed to meet the needs of space research and travel. One of the most unique and long-serving rockets (with a record of 10,000 launches) was undoubtedly Korolev’s R-7 rocket; successfully tested in August 1957, it launched the first artificial satellite, Sputnik-1, into orbit by October of the same year. Its first stage consisted of twenty nozzles, resulting in a base diameter of 10 meters. From that point on, a competition ensued between the Soviet Union and the United States. The race for supremacy culminated in a victory for the Americans in November 1967, with the inaugural launch of the Saturn-5 rocket, built by Von Braun’s team. Standing 110 meters tall and weighing 2,700 tons at liftoff, it could carry a 45-ton Apollo spacecraft to the moon, though only 18 versions were produced. Russia’s Energia was the world’s most powerful rocket from its introduction in May 1987 until its retirement in 1995 due to economic reasons.

Finally, France became the third space power in 1965 by launching the small satellite Astéris into orbit using the Diamant A rocket. The European Ariane rocket began its illustrious career in 1979; standing 48 meters tall, Ariane could launch payloads weighing up to 1,750 kg into geostationary orbit from the Kourou launch site in French Guiana. By 1996, Ariane-5 had achieved a launch capacity of 6,700 kg. The increase in payload sizes for these satellites was made possible by advancements in launch vehicle technology utilizing cryogenic propulsion (specifically using liquid oxygen and hydrogen).