Diphtheria: A Nightmare for Doctors and Families Alike

Even Noah Webster, known as the “father of American education” and a master of words, struggled to find the right terms to describe the dangers of diphtheria. He began addressing this disease in a well-known history of maladies, which horrified all who read it…

The “Demon” that Took the Lives of Thousands of Children

In May 1735, on a cold and damp day in a town in New Hampshire, the United States experienced an outbreak of a serious illness among young children. At that time, it was referred to as “the Care disease in the throat.” This malignant disease had an extremely high mortality rate, weakening the body, causing swelling in the throat, and inflicting severe pain on its victims.

This disease gradually spread southward, claiming the lives of many children across the nation. The sorrow of countless families during that time was unimaginable, with many parents losing 3-4 children, or even all of them.

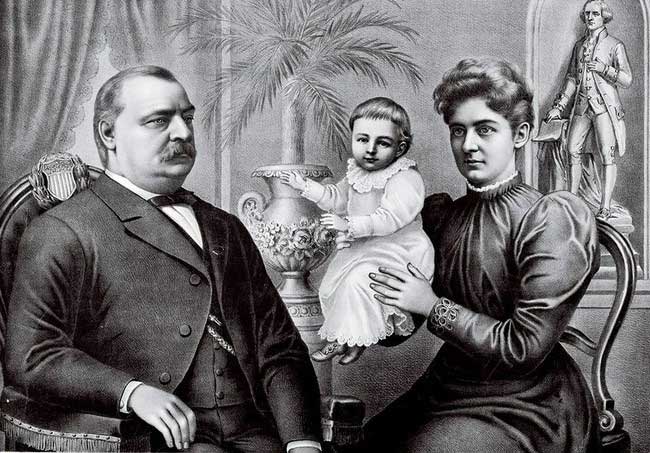

Families, rich and poor alike, suffered the loss of children due to diphtheria. (Photo Smithsonianmag).

In 1821, a French doctor named Pierre Bretonneau named the disease diphtheria, derived from the Greek word diphthera, meaning a membrane that forms in the throat of patients, making breathing and swallowing difficult. Because children’s airways are relatively small, those infected with this disease would struggle to breathe and eventually succumb in pain.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, diphtheria became a nightmare for most doctors, who were powerless to watch children perish. It instilled terror regardless of wealth. Queen Victoria’s daughter, Princess Alice, died from diphtheria in 1878 at the age of 35. Five of Alice’s children also contracted the disease, along with her husband, the Grand Duke of Hesse-Darmstadt.

Today, we understand that diphtheria spreads through droplets, or via coughing and sneezing. However, in the past, no one knew the true cause, rendering diphtheria a pandemic for many centuries.

The fear surrounding diphtheria was so profound that it was reported that many children would not survive past the age of 10. Consequently, many families raised their children in constant worry, hoping for their health and safety.

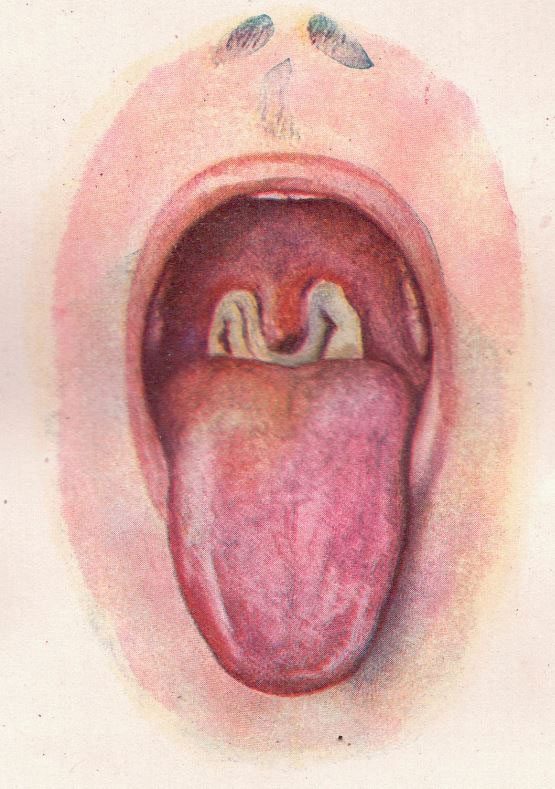

An illustration from the book The Practical Guide to Health published in 1913, intended to show parents that a gray patch in the throat could be a sign of diphtheria. (Photo Smithsonianmag).

Diphtheria: The Pain of Doctors and Patients

Many books and narratives by doctors and experts around the world mention diphtheria. Émile Roux, who was once an assistant to Louis Pasteur, shared that: “The pediatric wards in every hospital echoed with the painful cries of children. They wheezed, struggled to breathe… just looking at them, one could guess they were unlikely to survive.”

In January 1860, at a meeting of the New York Medical Institute, Abraham Jacobi, considered the father of American pediatrics, reported seeing 122 children with diphtheria at the Canal Street Clinic. At that time, he was the only one with foresight, while other doctors remained oblivious.

From then on, he began researching ways to save children afflicted with diphtheria. Unfortunately, in more than 200 attempts to perform tracheostomies to help patients breathe better, he largely failed.

Later, Jacobi married and had a son and a daughter. However, both of their children contracted diphtheria. Onlookers believed that the couple had brought the infection home. The daughter was fortunate to recover, but the son passed away at the age of 7…

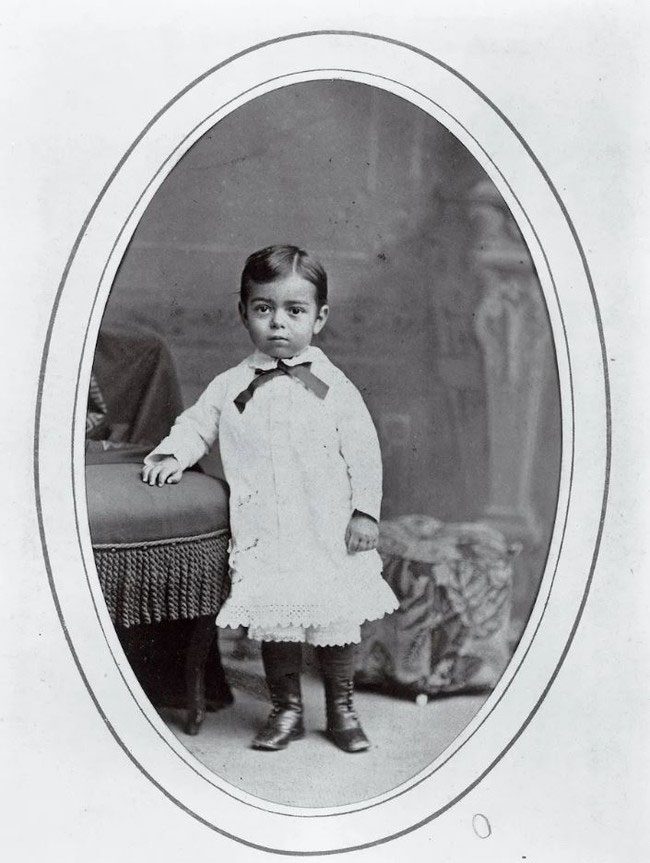

Jacobi’s son, Ernst Jacobi, died at the age of 7 from diphtheria. (Photo Alamy/Smithsonianmag).

W.E.B. Du Bois, the first African American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard, left Philadelphia in 1897 to pursue academic work in Atlanta. In 1899, his 2-year-old son, Burghardt, showed symptoms of diphtheria.

In his book The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois wrote about the death of his child. “And then one night, the tiny feet tiredly walked on the little white bed, the small hands trembled, and the warm rosy face rested on the pillow, and we knew the child was sick,” he wrote. “He lay there for ten days, a week passed quickly, and three endless days, withering away, fading away.”

Du Bois’s child also died young due to diphtheria. (Photo Smithsonianmag).

Unity: The Key to Survival

By the end of the 19th century, facing the rampant disease, scientists from around the world collaborated to identify the source of the illness. Eventually, they pinpointed the bacteria responsible, naming and detailing it further.

In 1883, a Prussian researcher named Edwin Klebs discovered a type of bacteria hidden in tissue, known as pseudomembrane, capable of blocking the patient’s airway – the primary cause of millions of deaths from diphtheria.

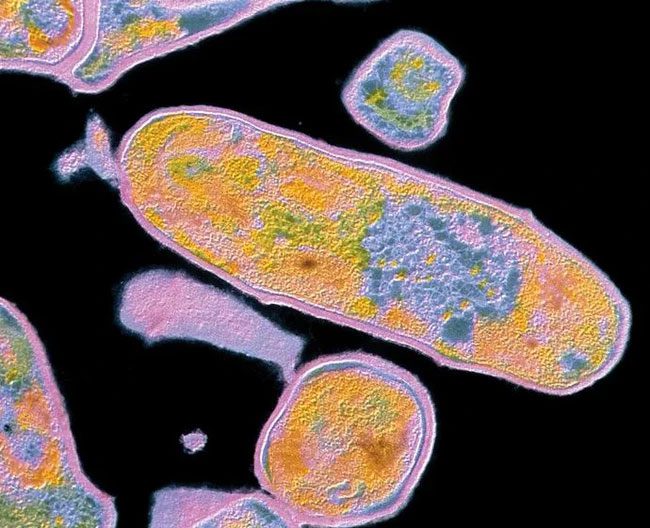

Image of diphtheria bacteria under a microscope.

Then, in 1888, Roux and Alexandre Yersin, medical doctors at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, made another significant breakthrough by demonstrating that a toxin produced by the bacteria was the specific culprit.

Another important advancement in the effort to “tame” diphtheria was achieved by microbiologists Emil von Behring and Shibasaburo Kitasato. After extensive research and analysis, they developed a serum against the disease in humans. They were awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1901 for this discovery.

This allowed Roux and two other colleagues to research and produce large quantities of similar serum, instead of taking as long as before. Experiments on 448 children with diphtheria showed that only 109 died, significantly increasing the survival rate.

Emil von Behring (right) produced large amounts of serum, saving thousands of children thereafter. (Photo Smithsonianmag).

Roux presented these results at the International Congress on Hygiene and Demography in Budapest in 1894. An American doctor later wrote that he had never seen “such a thunderous applause from an audience of scientists… Hats were thrown to the ceiling, and everyone stood up and cheered in every language of the world.”

Since then, the mortality rate from diphtheria drastically decreased in areas where serum was available or where modern healthcare infrastructure existed. With funding from the American Red Cross, followed by widespread support from the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, diphtheria vaccination became widespread among the populace.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that children receive the DTaP vaccine at 2, 4, 6, and 15 months of age, and then again between 4 and 6 years old. The World Health Organization (WHO) provides similar recommendations as the CDC, and officials in most countries urge parents to vaccinate their children.

Vaccinating children was the best way to combat diphtheria at the time.

Initially, the vaccine was met with skepticism because it caused many side effects, such as high fever and arm pain. At that time, doctors faced the challenge of persuading parents to have their children vaccinated. Just convincing them was like contributing a small part to the fight against diphtheria.

In a 1927 article in a Canadian journal, a doctor recalled the years before the serum became common, when he witnessed a beautiful girl, about five or six years old, suffocating to death. Later, the doctor’s own daughter contracted diphtheria, but a decade had passed, and now vaccines were globally available.

“Witnessing the terrifying membrane dissolve and disappear within hours, with the patient fully recovering within days, was one of the most impressive and thrilling experiences of my professional career,” the doctor reflected.

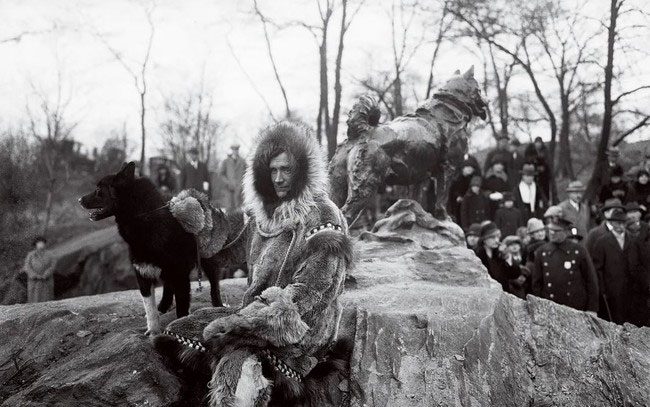

Image of a unit transporting 300,000 doses of diphtheria vaccine to Alaska.

It is evident that diphtheria has been a “nightmare” for the entire world in the past. However, humanity has eventually managed to push back this disease and continue advancing in medicine. Although diphtheria is re-emerging today, we can remain confident and follow the guidance of experts to effectively prevent the disease. Let’s stay optimistic, because at least we currently have a diphtheria vaccine!