When it comes to crystals, we might be quite familiar with them. For example, common table salt is primarily made up of sodium chloride crystals. But do you know what “time crystals” are? Why do researchers wish to create time crystals?

In many ways, scientists are similar to detectives; they try to solve mysteries by sifting through evidence to build models with similar characteristics and find answers. For instance, any crystal, whether a grain of salt or a diamond necklace, is ultimately just a series of atoms arranged in a repeating pattern. In this way, by looking at just a few atoms with a specific shape, you can infer the positions of all the other atoms.

But what if those laws are not expressed in space but in time? What if the relationship between different components is not “up, down, left, and right,” but “sequential,” “when” instead of “where”?

This counterintuitive concept is the basis of “time crystals”, a quantum state that exhibits predictable repeating behavior similar to crystals.

Initial Idea

The existence of time crystals was first theoretically predicted in 2012 by physicist and Nobel laureate Frank Wilczek from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. A space-time crystal extends the three-dimensional symmetry commonly seen in crystals to include the fourth dimension of time; a natural time crystal breaks the symmetry of time translation. This type of crystal does not repeat in space, but it can be in perpetual motion over time. Time crystals are closely related to the concepts of zero-point energy and dynamic Casimir effects. After years of diligent research, experimentalists were finally able to create a time crystal in 2021.

The key to understanding this special crystal is realizing that matter exists in different “phases.” For example, water has three common phases: ice, liquid water, and steam. A material can have very different properties depending on the phase in which it is found. Ordinary crystals—what could truly be called “space crystals”—are phases of such a substance. These crystals are characterized by a very regular arrangement of particles in space. In a time crystal, particles are arranged not only very regularly in space but also very regularly over time. These particles can move from one position to another and return without slowing down or losing energy.

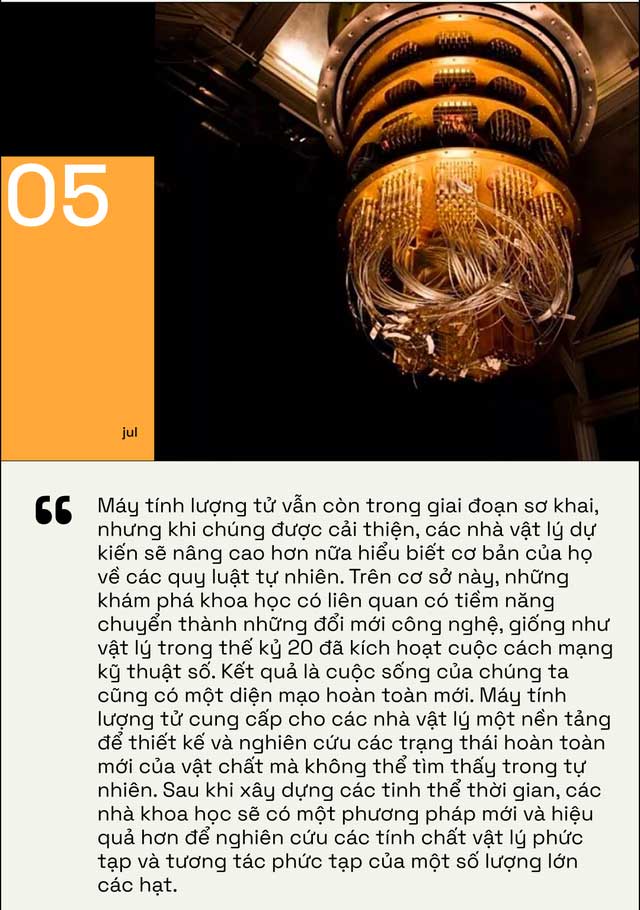

Now, a group of physicists led by engineer Hossein Taheri from the University of California, Riverside, has made another breakthrough by creating a time crystal out of light. Their work, published in Nature Communications in February, may help transform time crystals from a curiosity in subtle experiments into tangible components for devices.

Principles

Although the operation of a time crystal repeats over time, it is not as simple as a clock. Clocks require external energy to run, but for a time crystal, operating as “a clock” is precisely its most stable and natural state. In other words, a time crystal can change over time but will continue to return to its original shape.

This is completely contrary to thermodynamic balance as physicists understand it—once energy enters a system, it will inevitably dissipate over time, just like a pot of boiling water left at room temperature gradually cools down.

In contrast, a time crystal is akin to a pot of water that is always boiling and never cools down. According to some definitions, time crystals represent a new and unique state of matter, the most notable characteristic being that they violate the laws of thermodynamic equilibrium and remain unchanged. Thus, they could be used for precise timekeeping or for processing quantum information in the future.

How to Create Time Crystals

Time crystals have moved beyond the stage of pure theoretical concepts, and researchers are beginning to explore their engineering applications. However, scientists still have a long and arduous road ahead to get more time crystals out of the laboratory and into practical applications.

Determining whether an experiment creates time crystals often requires extremely complex and rigorous experimental setups that must also be monitored by powerful quantum computers.

In this new study, the team of scientists directed two laser beams into a chamber containing a disc-shaped crystal with a diameter of 1 millimeter. The two laser beams reflect within the chamber, continuously colliding. The researchers deliberately chose a specific chamber design and controlled the properties of the laser beams so that the reflected light from the lasers created a form not previously formed by ordinary light: the laser beams reflect back and forth within the chamber, forming multiple single waves. These waves have predictable periodicity and match the rhythm perfectly, allowing them to be regarded as a time crystal.

If you could take this crystal out of the chamber with a light detector, you would initially detect periodic variations in the intensity of outgoing light related to the properties of the laser. But at a certain point, the intensity of the light you detect would suddenly change. It would be like watching a movie on TV and suddenly the film starts to fast forward, the speed of the fast forward seemingly determined by some invisible mechanism on the screen, completely beyond your control.

We can also observe some periodic characteristics in these light waves, but these cycles are actually double, triple, or other integer multiples of the laser’s own cycle.

This is akin to hanging a string in saline to grow salt crystals. Adjusting the properties of the laser is akin to adjusting the structure of the string you put into the saline. Whether it’s the laser or the string, their roles are merely to help form the crystal, but the periodicity and repetition of the crystal are entirely determined by itself.

Future Applications

Previous studies have utilized various factors to create time crystals. However, this experiment demonstrates that using lasers to create time crystals has many more practical benefits. Most importantly, the time crystals generated by the team also function well under relatively normal conditions.

Most quantum states of matter must be exposed to extreme conditions, such as very low temperatures, to exhibit quantum properties. Berislav Buca, a physicist at Oxford University who did not participate in the research, stated: “In my view, this experiment is significant because it was conducted at relatively high temperatures. This brings it closer to the complex processes we observe in everyday life.”

As a timekeeping device, laser-based time crystals may be somewhat less accurate than atomic clocks. However, their stability and simplicity make them suitable for use in everyday devices. Additionally, some techniques for manufacturing electronic components could be used to integrate time crystals into chips, allowing systems to easily adapt to existing consumer products.

Physicists can study time crystals in the same way that traditional space crystals have been studied for decades, determining whether time crystals behave unexpectedly when they have certain deficiencies or are exposed to excessive energy. Of course, time crystals could also be used to study quantum systems, including quantum entanglement. In quantum entanglement, when you act on one particle, the other particle changes correspondingly, even if they are very far apart. This represents a completely new state of matter, a pristine territory, a new world waiting to be explored.