They say “seeing is believing,” but do you really trust what you see?

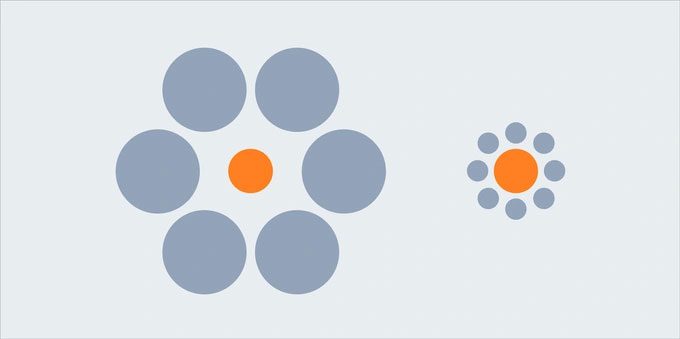

Looking at the image below, do you see two orange circles of the same size?

Orange Circle Illusion. (Image: Visme).

If your answer is yes, you have officially been deceived by an optical illusion. Even if you already know the answer, we still feel that the orange circle on the left is smaller than the one on the right. However, in reality, they are the same size.

This is a classic example of how optical illusions work. They can be seen as a challenge to our perception of reality.

Science suggests that we see by learning how to look. Our brains have evolved to identify patterns and create connections by interacting with the real world. It’s a survival instinct.

However, when a visual situation arises that differs from what our brain considers “the norm,” optical illusions will emerge.

This results from the brain’s response to unusual visual experiences, leading to interpretations that seem “inappropriate.”

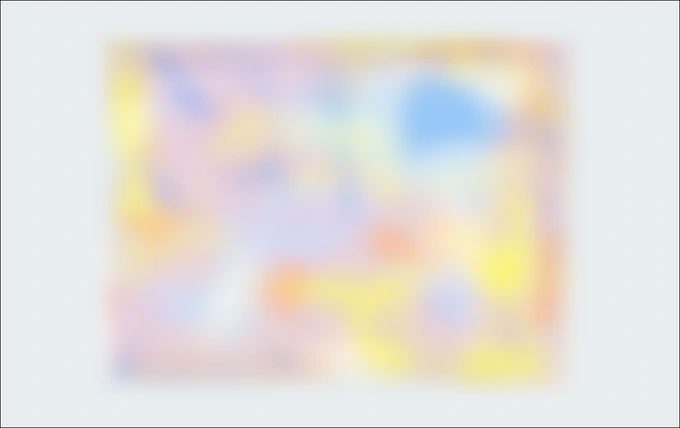

Troxler Effect. (Image: Visme).

Stare at the center of the blurred image above without blinking. After a few seconds, do you see the image starting to fade away?

This visual illusion is called the Troxler Effect, first discovered by Swiss physician Ignaz Paul Vital Troxler in 1804.

It reveals how our visual system adapts to sensory stimuli, specifically by ceasing to respond to stimuli that remain unchanged over time.

In this case, you can clearly see that the blurred image in the background has gradually faded from our consciousness.

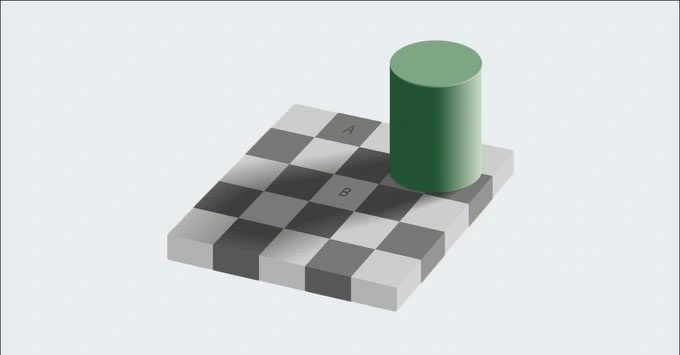

Checker Shadow Illusion. (Image: Visme).

In the famous visual illusion known as the “Checker Shadow Illusion,” the square marked A appears much darker than square B, right?

But in reality, they are both the same shade of gray.

This is a classic example of how our visual system cannot perceive absolute colors.

Here, the visual interpretation situation on the checkerboard is very complex: There is light shining on the surface, then a shadow cast by a cylinder, affecting both the light and dark squares.

This confuses our brain when determining the colors of squares A and B, leading to incorrect judgments.

Negative Afterimage Illusion. (Image: Visme).

After staring at the cross in the middle for a few seconds, you will begin to see a green dot moving around. Looking longer, we will see the purple dots seemingly disappear.

The effect known as “negative afterimage” occurs when our perceptual system adapts to fill in the gaps left by the “afterimage” of complementary colors on a neutral color.

In this case, the disappearance of the purple dots creates the appearance of complementary afterimages (green).

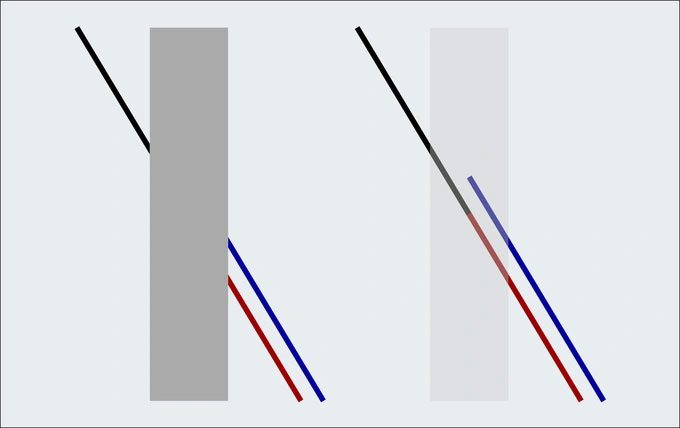

Poggendorff Illusion. (Image: Visme).

Looking at the image on the left, the black line seems to align with the blue line. However, in reality, the black line aligns with the red line, as shown in the image on the right.

Johann Poggendorff, a German physicist, first described this illusion in 1860. It reveals how our brain perceives depth and geometric shapes, but the cause of this optical illusion remains inadequately explained.

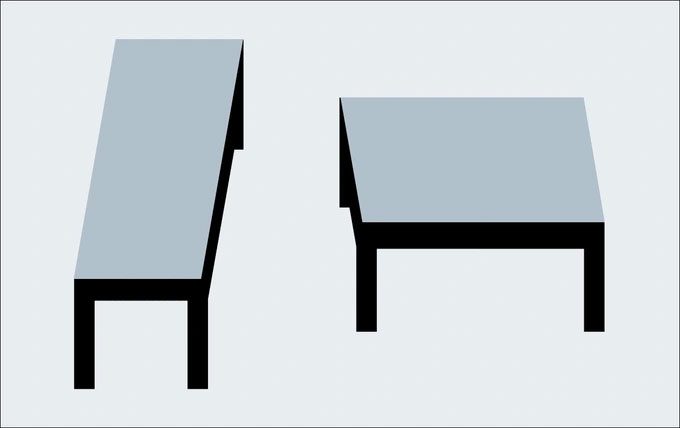

Shepard’s Illusion. (Image: Visme).

When looking at the two tables above, you will believe that they cannot be the same size. At least, the table on the left appears less square than the one on the right. However, in reality, these two tables are identical.

This simple yet astonishing visual illusion was presented by American psychologist Roger Shepard in his book Mind Sights (published in 1990).

It shows that our visual system is largely influenced by our experiences with the outside world and can sometimes interfere with reality.

Specifically in this illusion, the perceptual error occurs because our brain cannot help but interpret 3D images from 2D representations, perceiving vastly different sizes due to foreshortening.