Scientists have created the first 3D images of tiny fossils dating back 850 million years, using pre-existing laser technology. They didn’t even have to break the surrounding rock fragments to do this.

In the future, this technique could help researchers understand when life truly began on Earth and determine whether life forms ever existed on Mars.

|

|

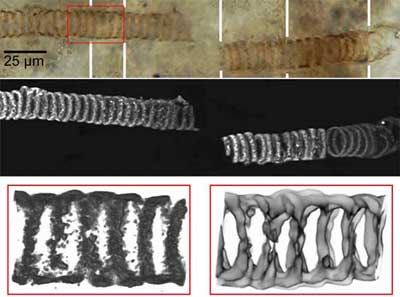

A 650-million-year-old fossil from Kazakhstan. Top: standard photo of the cyanobacterium fossil. Middle: image captured using the confocal microscopy technique. Bottom left: close-up of the optical image. Bottom right: Raman chemical image of the selected area. (Photo: LiveScience) |

Geologists have struggled to study these ancient single-celled organisms due to their size—about 1/50th the diameter of a human hair—making them extremely difficult to locate and photograph.

Previous 2D images only allowed researchers to make subjective inferences about their size and shape. With the application of two new techniques: confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) and Raman spectroscopy, they can now investigate inside rock formations to search for signs of life.

“We can now observe tiny microscopic filaments in 3D, inside the rocks, showcasing all their wonderful beauty,” said J. William Schopf, the lead researcher from the University of California, Los Angeles.

Initially, CLSM was developed to study the internal structures of living cells. It produces high-resolution 3D images of specimens. Meanwhile, Raman spectroscopy is used in chemistry to visualize the molecular and chemical structures of microorganisms in three dimensions. Raman spectroscopy will help determine whether the fossils are indeed biological specimens or just ancient rocks.

Both techniques use lasers directed at a fossil. Carbon molecules fluoresce when exposed to a laser beam. By capturing all fluorescent points, scientists can connect these bright spots to create a 2D image of the fossil. From multiple 2D images, a computer generates a 3D model that can be rotated for observation from any angle—something that was nearly impossible before.

Unlike other magnification techniques that rely on powerful microscopes, this new process ensures that the tiny fossil specimens remain undisturbed within the rock and are not damaged or contaminated.

T. An