To calculate significant and precise measurements on a galactic or cosmic scale, a precise constant is needed as a reference point. One could say that the Hubble constant is as essential to the universe as Pi is to a circle.

Anyone studying astronomy knows that the universe is constantly expanding. However, the exact rate of this expansion is something even the most distinguished scientists hesitate to assert definitively.

This rate of expansion of the universe is named the Hubble constant. Modern measurements have yet to reach a consensus on the value of this constant, as every different measurement yields a different value.

Illustration of Quasar ULAS J1120+0641 powered by a black hole 2 billion times the sun. (Image: ESO).

What is the Hubble Constant Used For?

For a long time, there have been two theories explaining the existence of the universe: One is that it has always existed, and the other is that it began from a single point. The first hypothesis was dismissed in the late 1960s when it was confirmed that the Big Bang explosion gave birth to the universe.

As early as the 1920s, scientist Edwin Hubble paid attention to the questions surrounding the Big Bang event. How long ago did this explosion occur? How large has the universe become?

Using technologies akin to today’s radar guns, Hubble discovered that galaxies are not only moving away from Earth but also away from each other. The relationship between the speed of galaxies’ movement and their distance from Earth is represented through the Hubble constant.

Thanks to the Hubble constant, scientists have been able to answer the first question. The Big Bang occurred approximately 13.7 billion years ago.

Measuring the Rate of Expansion of the Universe

The fundamental idea behind measuring the rate of cosmic expansion, or the value of the Hubble constant, is to observe luminous sources from great distances. Specifically, these sources include supernova explosions (the explosion marking the end of a star’s life) or standard candles (Quasars – extremely distant and bright celestial objects with characteristic redshift). These light sources are powerful enough and far enough away for scientists to measure their redshift intensity.

The redshift phenomenon is when the light from an object moving away from the observer shifts towards longer wavelengths, specifically the red end of the spectrum, due to the Doppler effect between two moving light sources. The greater the redshift, the faster the object is moving away. Therefore, if an accurate number can be measured, the rate of expansion of the universe can be calculated.

The rate of expansion of the universe is measured in kilometers per second per megaparsec (kps/Mpc), symbolized as (km/s)/Mpc. This unit can be simply understood as follows: Suppose there is a space expanding at a rate of 10 (km/s)/Mpc, this means that two points in that space are 1 megaparsec (3.26 million light years) apart and are moving away from each other at an additional 10 kilometers per second.

When the universe was first discovered to be expanding in the 1920s, scientists estimated the rate of expansion to be 625 kps/Mpc. However, since the 1950s, more accurate measurements have indicated that this rate is below 100 kps/Mpc. In recent decades, many studies suggest the rate of cosmic expansion is around 76-77 kps/Mpc.

However, the result must be an exact number rather than a range. This number is crucial as it serves as a benchmark for other physical ratios in the universe. Without an accurate number, astronomers cannot measure the sizes of galaxies or the history of the universe’s expansion.

All the physical and scientific discoveries we have on Earth are on an incredibly small scale. To calculate larger, more accurate measurements on a galactic or cosmic scale, a precise constant is needed as a reference point. The Hubble constant can be compared to the Pi constant in relation to circles.

However, recent research may resolve this discrepancy by observing standard candles and gravitational lenses in the universe.

Gravitational Lenses in the Universe

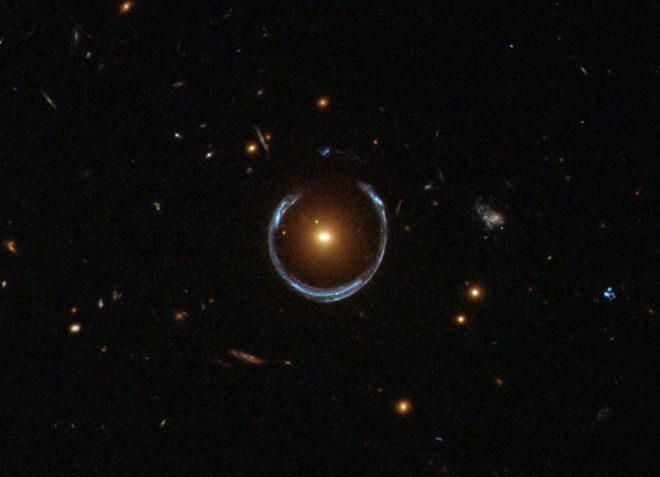

Gravitational lensing is not a physical object like the optical lens of a camera but rather a phenomenon.

Galaxies or black holes often have immense mass, to the point that any light passing through them is bent. This is the phenomenon of gravitational lensing. Unlike optical lenses, light is bent the most at the gravitational center and weakens as it reaches the edge of the black hole or galaxy (optical lenses do not bend light that is directly aimed at them at a 90-degree angle but bend light at the lens’s edge).

Thus, any light from distant quasars or supernova explosions reaching Earth must pass through a black hole or galaxy, where it will be bent by the gravitational lensing phenomenon.

The Hubble Space Telescope observed a red galaxy bending the light of a much farther blue galaxy. This is the phenomenon of gravitational lensing. (Source: ESA).

Standard Candles (Quasars) and Cosmic Benchmarks

Standard candles are extremely distant and bright celestial objects with significant redshift. In the visible spectrum, a quasar appears similar to an ordinary star, a point of light. In reality, it is light emitted from dense matter halos surrounding the cores of active galaxies (young galaxies), usually containing supermassive black holes.

Because quasars are so bright, they are easily visible from great distances and have become a leading subject of study. Recent research indicates they could provide clues for calculating the Hubble constant when combined with gravitational lensing phenomena.

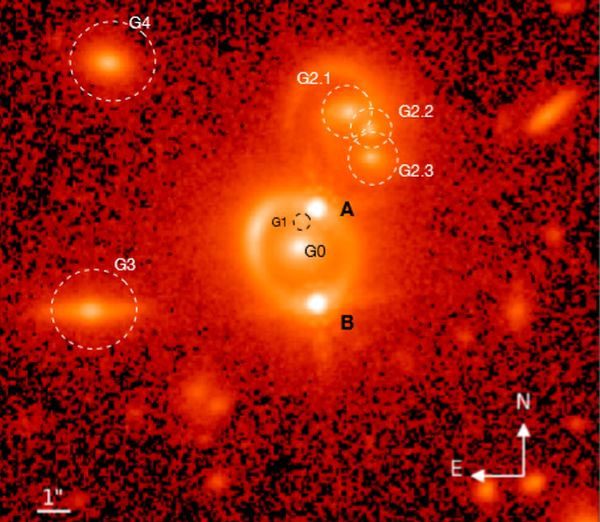

Scientists have found a clue in a double quasar. A double quasar is not two quasars located near each other like a binary star or binary galaxy. It is the image of a single quasar whose light is bent by gravitational lensing, following two paths to reach Earth.

Studying the two images of the same quasar reveals they have a delay each time the parent quasar flares up. By measuring the time delay between two flares, combined with the known mass of the lensing galaxy, scientists calculate the distance from Earth to the lensing galaxy and quasar. Knowing the redshift of both the galaxy and quasar allows scientists to calculate the rate of expansion of the universe.

After years of observing the double quasar SDSS J1206+4332, combining dozens of data from the Hubble Space Telescope and the COSMOGRAIL gravitational lensing observation network, scientists calculated the time delay between two flares of the quasar, yielding the most accurate Hubble constant calculation to date.

“The beauty of this measurement is that it is independent of previous measurements,” said Professor Tommasso Treu, the study’s author.

The lensing galaxy marked G0 in the image. A and B are images of the double quasar SDSS J1206+4332. G2 is the triplet galaxy. G3 and G4 are nearby galaxies. (Image: Hubble Space Telescope).

The research team concluded that the value of the Hubble constant is 72.5 kps/Mpc. This result aligns with measurements obtained from supernova explosions, but is 7% higher than measurements using cosmic microwave background radiation (the electromagnetic radiation produced from the early universe, about 380,000 years after the Big Bang).

The matter is not yet resolved, as if there are still discrepancies between different measurement methods for the same constant, the scale of the universe remains “unresolved.” In fact, all three measurements could potentially be incorrect. The research team intends to search for even more distant quasars to provide a more accurate measure of the universe’s expansion constant.