Nuclear fusion reactions are the opposite of those occurring in nuclear power plants, and they have the potential to create an endless source of energy.

Why Haven’t We Tapped into the Endless Energy of Nuclear Fusion?

Nuclear fusion is the energy source for the Sun and stars, releasing tremendous amounts of energy by fusing light elements together, such as hydrogen and helium. If this fusion energy could be harnessed directly on Earth, it could provide a clean, endless energy source, using seawater as the primary fuel without emitting greenhouse gases, without a rapid increase in risk, and without the threat of catastrophic accidents.

The amount of radioactive waste produced is very low and indirect, mainly from neutron activation of the nuclei. With current technologies, a nuclear power plant can be reused for about 100 years before being decommissioned.

Today’s nuclear power plants derive energy from nuclear fission – the splitting of heavy atoms such as uranium, thorium, and plutonium into smaller nuclei.

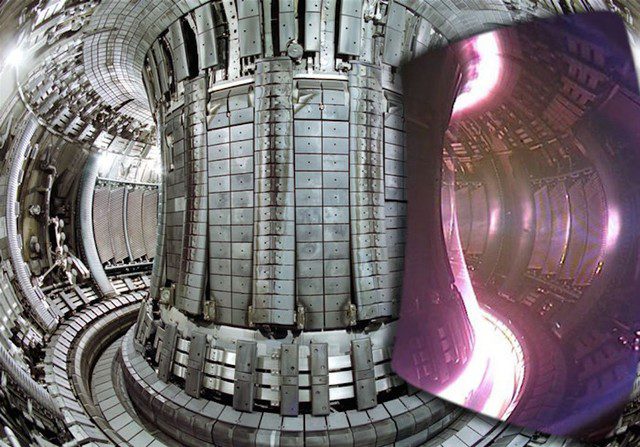

Joint European Torus

This process occurs spontaneously in unstable elements and can be exploited to generate electricity, but it also produces a significant amount of long-lived radioactive waste.

So, why haven’t we utilized the clean and safe energy from nuclear fusion? Despite significant breakthroughs in research in this area, why do physicists remain skeptical about what is considered a “breakthrough for humanity”?

The short answer is that achieving the conditions necessary to sustain this reaction is extremely challenging. However, if ongoing experiments can succeed, we may be optimistic about nuclear fusion energy becoming a reality in the near future.

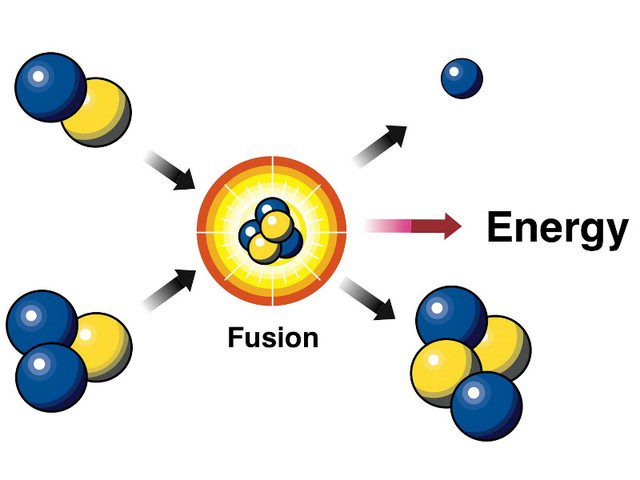

Unlike nuclear fission, nuclei do not spontaneously undergo fusion: positively charged nuclei must overcome their immense electrostatic repulsion before they can get close enough for the strong nuclear force to bind them together.

In nature, the immense gravitational forces of stars are sufficient to maintain the temperature, density, and volume of their nuclei to sustain fusion through the “quantum channels” of electrostatic barriers. In the laboratory, the appearance of quantum channels is too low, and therefore, the electrostatic barrier can only be overcome by increasing the temperature of the energy nuclei – heating them to 6-7 times that of the Sun’s core.

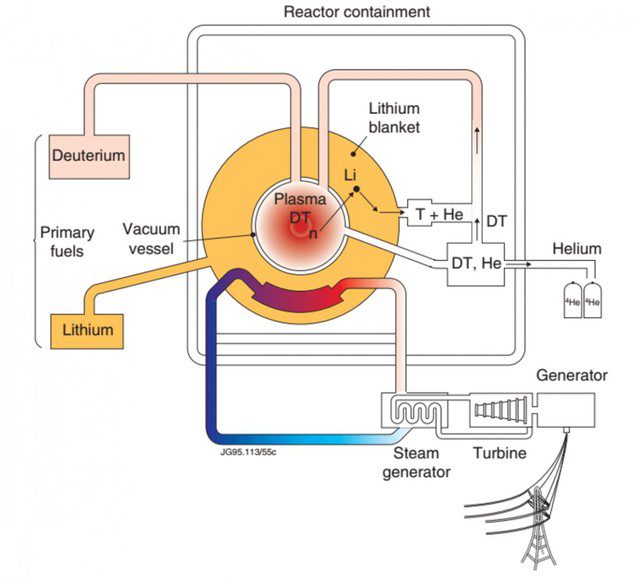

Even the easiest nuclear fusion reaction to initiate – the fusion of hydrogen isotopes such as deuterium and tritium to form helium and a high-energy neutron – requires temperatures of about 120 million degrees Celsius. At such extreme temperatures, energy atoms break down to release their electrons and nuclei, creating a superheated plasma.

Stabilizing this plasma state long enough for the nuclei to fuse is no trivial achievement. In laboratories, the plasma is confined by a strong magnetic field, formed by charged superconducting coils, creating a “magnetic bottle” that traps the plasma inside.

Current plasma experiments, such as the Joint European Torus, can maintain plasma at temperatures suitable for power amplification, but the density and energy confinement time (the time it takes for the plasma to cool down) are too low for it to self-heat.

However, this process has seen some progress – current experiments have achieved reactions that are 1,000 times more efficient in terms of temperature, plasma density, and confinement time compared to experiments conducted 40 years ago. And now we have promising ideas for accelerating the process.

System Changes

ITER reactor, currently under construction in Cadarache, southern France, will explore the “plasma burning system”, where the thermal energy of the plasma produced from the nuclear reaction will exceed the external thermal energy. The energy obtained from ITER will be more than five times the external thermal energy in adjacent projects and will appear in a timeframe 10-30 times shorter.

With costs exceeding $20 billion and funded by a coalition of 7 countries along with other allies, ITER is the largest scientific project on the planet. Its aim is to demonstrate the scientific and technological feasibility of using nuclear energy for peaceful purposes such as electricity generation.

The challenges for engineers and physicists are immense. ITER will have a magnetic field strength of about 5 Tesla (100,000 times that of Earth’s magnetic field), and a component radius of about 6 meters, containing approximately 840 plasma units with a 6-meter side length (one-third the length of an Olympic-sized swimming pool). It is estimated to weigh around 23 tons and contains about 100,000 kilometers of superconducting wire made from niobium-tin. The entire machine will be immersed in a cooling device using liquid helium to keep the superconducting wires at just above absolute zero.

ITER is expected to start producing its first plasma units in 2020. However, plasma burning experiments will not be ready to commence until 2027. One of the significant challenges is to observe whether these self-sustaining plasma units can be created and maintained without damaging the surrounding walls (or “targeting” the extreme heat flow).

What is learned from the construction and operation of ITER will aid in designing future nuclear fusion plants, with the ultimate goal of utilizing the technology for energy production. At this point, it seems that prototypes will begin to be constructed in the 2030s, with the potential to generate about 1 gigawatt of electricity.

The first generation of nuclear fusion plants will be significantly larger than ITER, and improvements in confinement and magnetic control are expected to lead to higher efficiencies. Thus, they will be less costly than ITER, with expectations of longer lifespans and lower environmental impacts.

Challenges remain, and costs are still sky-high. All we need to do is to get to work to swiftly end the nightmare of energy crises and environmental pollution.