The Khitan people are a martial and valiant ethnic group. At their peak, the Khitan dynasty, known as the Liao Dynasty, occupied half of China’s territory.

On June 21, 1922, Kervan, a Belgian missionary, arrived in Batingue County, Inner Mongolia (China) to preach. He was taken by believers to view an ancient tomb that had been ravaged by thieves. There, he discovered a stone tablet engraved with strange symbols resembling an unusual script that the locals referred to as “heavenly scripture.”

The Mystery of Heavenly Scripture

According to research, this is the tomb of a Khitan who died approximately 900 years ago. Could the strange symbols in the heavenly scripture be the writing of the ancient Khitan?

Historical records indicate that the Khitan established the Liao state in 907 and created the Khitan script. However, around 900 years ago, the Khitan writing was lost, and later generations could not read it even if they saw it. Experts speculate that the heavenly scripture represents Khitan writing that has been buried for centuries. Since then, in the vast territory of the Liao state, many explorations and excavations have occasionally revealed various scripts and historical artifacts of the Khitan people.

In 1986, in Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, an ancient joint tomb of a Khitan princess and her husband was discovered. This tomb contained the most valuable burial artifacts found to date. The burial practices and accompanying items indicate that the Khitan were significantly influenced by the Han culture of the Central Plains.

Although the remains in the tomb have decayed, the delicate silver mesh and thin gold leaf covering the remains indicate the noble status of the tomb’s owner during their lifetime. The burial goods, ranging from gold and silver to jade, precious stones, and exquisite ceramics and precious wood, demonstrate an extraordinary level of craftsmanship at the time.

Khitan (Qidan) originally means “Steel Wind,” implying extreme toughness and resilience. They are a martial and valiant ethnic group. Over 1,400 years ago, the Khitan appeared in the Book of Wei as a people from northern China. They were known for their strong warriors and fierce combat skills. A tribal leader named Yelii Abaoji unified the Khitan tribes. In 916, he established the Khitan state, which was renamed Liao in 947.

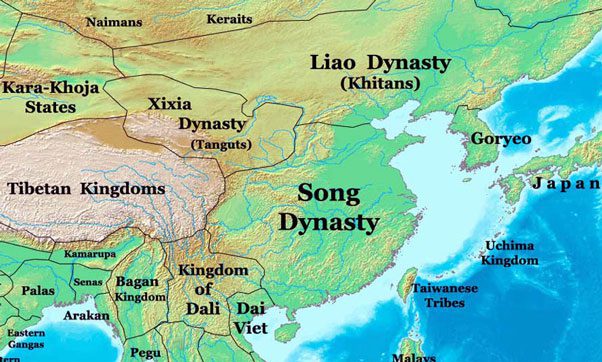

At their height, the Liao dynasty occupied half of China. Their territory was vast, stretching north to Lake Baikal, beyond the Greater Khingan Range; east to Sakhalin; west beyond the Altai Mountains; and south to Hebei and northern Shanxi today. They could be considered the overlords of their domain.

The Khitan dynasty known as the Liao ruled northern China for over 200 years, creating a confrontational situation with the Northern Song dynasty. During this period, the Silk Road trade route from China to the West was cut off, leading to the misconception among Eurasian countries that all of China was under Khitan domination. Thus, Khitan suddenly became synonymous with China.

Marco Polo, in his travelogue introducing the East to the West, referred to China as Khitan. To this day, Slavic-speaking countries still refer to China as Khitan (Kitan or Kitai).

The Khitan established a powerful military kingdom and a brilliant culture. The Liao temples and pagodas reflect their level of civilization. To this day, ancient temples and pagodas have been preserved along the northern bank of the Yellow River. These structures are grand and majestic, standing resilient against the elements for over a thousand years.

The Sakyamuni Pagoda in Yung County, Shanxi Province, is the oldest and tallest wooden pagoda globally, having survived several earthquakes without damage. A civilization that created such brilliance must have had a robust economic foundation and formidable technical strength.

The Khitan dynasty also assimilated various aspects of culture. Besides attracting a large number of talents from the Han people of the Central Plains, they also learned many advanced production techniques through trade with the Song dynasty. It is evident that the Khitan ushered in an era of prosperity in northern China.

The Fall of the Liao Dynasty

Historical records state that the Liao faced off against the Northern Song for over 160 years. Ultimately, the Liao was defeated by the Jurchen people (Niizhen), who had once been subjects of the Khitan.

The leader of the Jurchen, Wanyan Aguda (Hoàn Nhan A Cốt Đả), led a large army to conquer Liao territory. Once their territory expanded and their population increased, Aguda established the Jin dynasty in 1115. Ten years later, the Jin replaced the Khitan dynasty.

A portion of the surviving Khitan gathered the royal family members and fled westward, establishing the Western Liao dynasty in Xinjiang. They founded the Hala Khitan state. This empire thrived for a time but was ultimately destroyed by the forces of Genghis Khan. Later, remnants of the Khitan fled to present-day southern Iran, establishing the Qierman dynasty, which soon also fell.

Within the territory of China, from the establishment of the Khitan dynasty (916) to the Yuan dynasty (1271), more than 300 years saw the emergence of the Liao, Northern Song, Western Xia, Jin, Southern Song, and Yuan dynasties… This was a particularly unique period in history as the ruling powers were successively held by different ethnic groups.

Thus, the rise and fall of the dynasty also led to the fate of the entire ethnic group. The corresponding culture underwent transformations as well. The Jin dynasty, after seizing power from the Khitan, ordered a thorough purge of the Khitan people who resisted. Historical records indicate that there was a massacre lasting over a month. It is highly likely that Khitan culture was also eradicated during this period.

When the Jin dynasty was established, they did not yet have their writing system and had to borrow Chinese characters to create Jin script. The Jin emperor officially decreed the complete elimination of Khitan writing, which may have led to the disappearance of Khitan script.

Descendants of the Khitan

The Khitan were a significant ethnic group but are not listed among the 56 ethnic groups in China today. As researchers sought evidence of the Khitan people, the Dawr ethnic group residing at the junction of the Greater Khingan, Nonjiang, and Hulunbeier grasslands particularly attracted attention.

Local legends tell that nearly a thousand years ago, a unit of Khitan troops was dispatched to this area to build fortifications along the border. They settled there permanently. The highest-ranking commander of this border troop was Sagil Dihan, who is considered the ancestor of the Dawr people, a minority community in today’s China.

By comparing production methods, lifestyles, customs, religions, languages, and histories between the Khitan and Dawr peoples, scholars have found substantial evidence indicating that the Dawr have inherited the most traditions from the Khitan. However, this is still indirect evidence and cannot yet be confirmed.

Scientists have decided to conduct DNA analysis to unveil this mystery. They collected and compared DNA from an arm bone believed to belong to a Khitan woman found in Leshan, Sichuan Province; teeth and skull bones of ancient Khitan discovered in an ancient tomb in Chifeng, Inner Mongolia; and blood samples from the Dawr people. Ultimately, they concluded that the Dawr people have the closest genetic relationship with the Khitan. They are indeed the descendants of the Khitan.

Historians have finally uncovered what they sought about the Khitan people. The Mongols, under Genghis Khan’s leadership, established the Mongol Empire across the Eurasian continent, conquering everywhere, leading to manpower shortages and continuous recruitment. Young, skilled Khitan men were compelled to battle, dispersing across various regions, with some maintaining relatively large communities, such as the Dawr. Others quickly assimilated with local populations, becoming the hidden descendants of the Khitan.