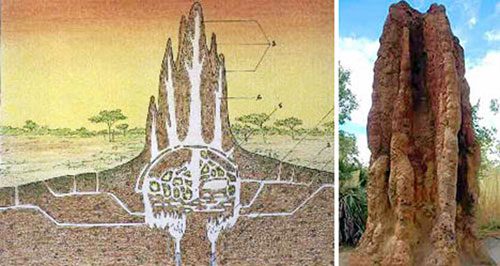

In the heart of the vast African grasslands, there stands a model “city” renowned for its environmental friendliness. The towers are constructed entirely from biodegradable materials that easily decompose in nature. The residents of this city live in cool, ideally humid areas without consuming a single watt of electricity. This is not a science fiction story, but the reality of a “city” of… termites.

As climate change issues become increasingly urgent, more and more experts in biology and architecture are turning their attention to the “masterful” building methods of termites, according to the journal New Scientist. In the past, some scientists have explored this topic, but their research findings were not widely disseminated or applied. Swiss entomologist Martin Luscher began studying the architecture of termite mounds from the genus Macrotermes in the 1960s. He discovered that the construction methods are directly linked to the eating habits of termites. The primary food source for these insects is cellulose from wood, which is notoriously difficult to digest. Termites have “cultivated” certain types of fungi capable of transforming this “hard-to-swallow” food into easily absorbable nutrients. However, the “farming” environment must be cool and at the right humidity, which is no simple feat in the tropical climate of Africa. Termite mounds must have an extremely efficient ventilation system.

Termites are masters of environmentally friendly architecture – Photo: Tdrinc

According to expert Scott Turner from New York University (USA), the outer walls of termite mounds are constructed in such a way that only slow-moving air currents can “sneak” inside. As a result, inside the termite mound, waste gases and fresh air continuously circulate, ensuring proper gas exchange. In other words, this unique architecture allows the termite mound to function like a gigantic lung.

Moreover, termites are adept at altering their building strategies to adapt to their environment. For instance, in excessively hot conditions, these talented “architects” will “bury” the mound deeper into the ground, effectively regulating temperature. To maintain humidity, they line the base of the mound with a mixture of chewed wood and grass. This mixture acts like a “super sponge,” capable of absorbing and “releasing” up to 80 liters of water to balance the moisture within the mound. These insights certainly provide valuable lessons for humanity as we move towards “ecological” cities in the future, Mr. Turner noted.