What may seem like trash to you is a valuable treasure in the eyes of others. In China, countless artifacts, even national treasures, have wandered among the common people, deemed as garbage or waste.

This saying is particularly relevant in the fields of archaeology and cultural heritage preservation. In China, there have been numerous artifacts, even national treasures, that were lost among the populace and regarded as rubbish or scraps. Yet, due to some fortunate coincidence, they were discovered, preserved, and saved.

The national treasures listed below are exemplary cases of a difficult journey from “waste” to being showcased in museums.

Jade Pig Dragon from the Hongshan Culture

In August 1971, Zhang Fengxiang, a resident of Sanxing Tala village in Wengniute, Inner Mongolia, unexpectedly discovered a cave covered with stone blocks in the forest.

Curious, he decided to explore the cave. At the bottom, Fengxiang found what resembled a piece of iron, but at that moment, he didn’t pay much attention to it. After returning home, he thought carefully; even if it was scrap iron, he could sell it for money. So he returned to the cave and took the “piece of scrap iron.”

However, Zhang Fengxiang did not sell it to the waste collection station but instead brought it to the Wengniute Cultural Center.

At that time, the Hongshan culture had not been discovered yet. The staff at the cultural center were also unaware of what the iron piece was, and Zhang Fengxiang did not know its worth either. An employee there purposefully offered Fengxiang 30 yuan to buy the item. Later, it was revealed that this was a valuable artifact from the Neolithic period.

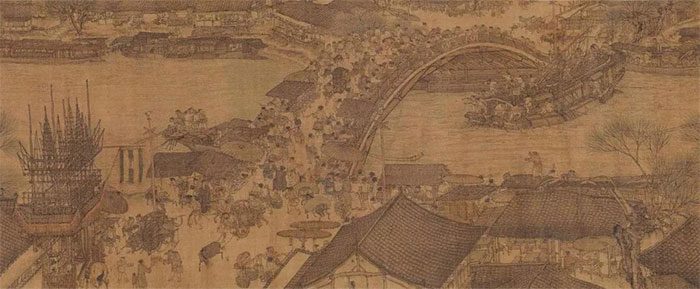

Along the River During the Qingming Festival from the Northern Song Dynasty

Painted during the Northern Song Dynasty, “Along the River During the Qingming Festival” has a history of nearly a thousand years and has undergone a long journey from the palace to the common people and back again. In 1911, this painting, originally stored in the Qing palace, was stolen by Puyi and taken to Northeast Manchukuo. In 1945, following Japan’s defeat and the dissolution of Manchukuo, Puyi fled. A large number of treasures were destroyed, and it was believed that the painting had been burned during the war.

Surprisingly, in 1951, while organizing the Northeast Cultural Museum, scholar Yang Renkai discovered this painting among a pile of waste.

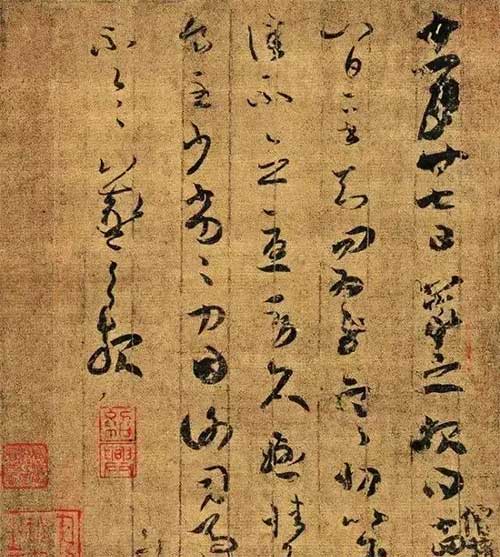

Han Tie Tie by Wang Xizhi

Han Tie Tie is regarded as the divine calligraphy work of the famous calligrapher from the Eastern Jin Dynasty, Wang Xizhi. The simple brushwork conveys profound meaning. This calligraphy was taken by Puyi from the palace early in the last century and subsequently went missing for several decades.

In the 1960s, many folk paintings were collected at a waste collection station, most of which were thrown into a mixer and turned into pulp. As a cultural heritage appraiser, Liu Guangqi’s task was to rescue valuable cultural relics from the waste, a task as difficult as finding a needle in a haystack.

A serendipitous event occurred when Liu Guangqi was at a waste collection station on Taihu Road in the Haidai District of Tianjin and discovered a roll containing paper with a striking appearance. Upon opening it, Liu was astonished to find two famous calligraphy pieces by Wang Xizhi: one was “Han Tie Tie” and the other was “Can Ou Tie”, both of which had been lost by Puyi.

Four Directions Wine Vessel from the Shang Dynasty

This is a highly valuable artifact from the Shang Dynasty. This wine vessel is a typical representative of jar products from the Shang to the Zhou Dynasty, featuring a wide mouth, tall neck, and round or square shape, intricately carved with the twelve zodiac animals like goats, tigers, elephants, horses, and phoenixes. After the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, this type of jar became less common.

This ancient vessel was excavated by some farmers in Hunan in 1938. It was later sold to an antique dealer for 248 silver dollars at that time. When these dealers went bankrupt, the ancient vessel was rediscovered and reclaimed by the government of the Republic of China.

During World War II, Changsha was bombed by Japanese troops, and the ancient vessel also went missing. It wasn’t until 1952, under the search efforts of the cultural and heritage department, that the vessel was found in the corner of a warehouse in a broken state, shattered into dozens of pieces. After nearly a year of restoration, the vessel was returned to its original form and became a national treasure.

Wine Vessel from the Western Zhou Dynasty

This artifact is the earliest evidence mentioning the term “China.” The vessel has 12 lines of inscription, comprising 122 characters, including the four characters “Zhe Zi Zhongguo,” recording King Cheng’s succession to King Wu and the establishment of Zhou Cheng (now Luoyang).

In 1963, a farmer discovered the vessel on a dirty rock wall behind his house. Unaware of its significance, the farmer used it as a food container. Later, this individual sold the vessel as scrap metal for 30 yuan! Fortunately, it was rediscovered by a museum expert in the waste storage and repurchased.

Bronze Artifact from the Western Zhou Dynasty

This is a bronze artifact from the Western Zhou period currently housed at the Beijing Museum. This artifact has over 3,000 years of history, with 198 characters inscribed inside, chronicling Mao Baiban’s suppression of rebellions, rewarded by the king of Zhou. This artifact was first excavated during the Northern Song Dynasty and subsequently added to the royal collection. However, in 1900, when the Eight-Nation Alliance invaded China, it disappeared during the war.

It was not until over 70 years later that this artifact was found by staff working at the cultural site in Beijing, discovered among scrap metal about to be sent to the furnace, granting this national treasure a second life!

Inscribed Vessel from the Shang Dynasty

This inscribed vessel from the Shang Dynasty is currently held at the Hunan Museum. It was discovered in 1962. At that time, cultural heritage experts were browsing through central waste recovery areas in search of national treasures when they stumbled upon this vessel.

The copper scrap from the recycling station was gathered from various locations, and at that moment, the experts noticed a particularly unique piece of copper. They felt it was different from other scrap metal, prompting them to search and explore further.

Eventually, they found over 200 pieces of copper among that scrap, contained in 27 bags. After a period of reconstruction, this treasure was restored to its original state as we see it today.

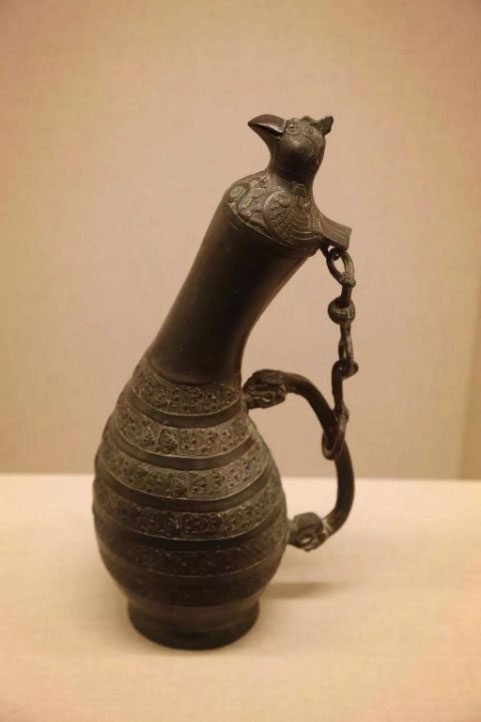

Bronze Wine Vessel from the Warring States Period

In 1967, at a waste collection station in Tuo De, Shaanxi Province, a cultural heritage staff member keenly spotted an object about to be sent to the furnace that had an “unusual” appearance.

Upon examination, it was identified as an exquisitely crafted bronze vessel from the Warring States period, recognized as a national first-class cultural treasure. This bird-shaped vessel holds invaluable cultural and artistic significance.

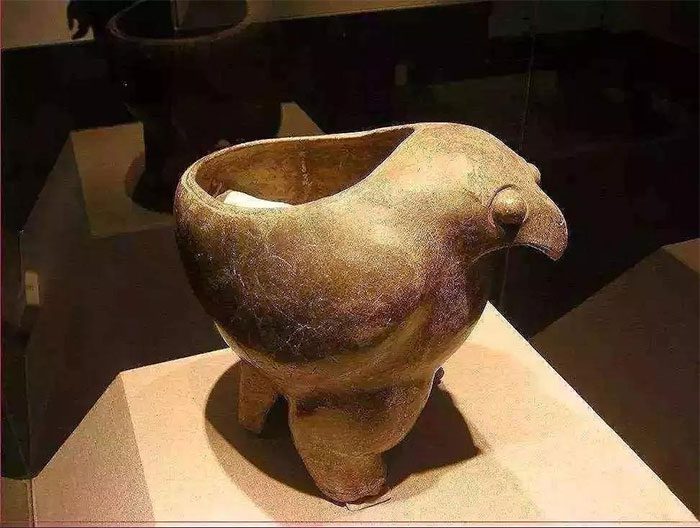

Dao Ying Ding from the Neolithic Period

Antiques are incredibly valuable. They not only reflect the wisdom of ancient people but also serve as evidence for modern individuals to understand the distant past. It is often difficult for ordinary people to discern the authenticity and value of antiques. Some individuals may discover these relics without realizing their true worth, treating them as ordinary objects.

One day in 1957, Yen Tu Nghia, a farmer from Thai Binh village, was plowing the eastern part of the village when he suddenly felt his plow strike something hard. He thought it was a stone. However, as he continued to dig, he discovered a porcelain object shaped like a bird, which he had no idea would later become the famous artifact known as the Hawk-Shaped Vessel (a porcelain vessel in the shape of a hawk).

Believing that the vessel was still usable, he took it home and used it as a food bowl for his chickens, thinking it quite practical. Little did this man know that the ceramic jar was actually a first-class cultural relic. A year after finding the jar, a team of archaeologists uncovered the Yangshao Culture Site in the nearby Quan Ho village in Hua County.

The old man suddenly recalled the ceramic jar he had found a year prior. He thought to himself, since Thai Binh village is close to Quan Ho village, and the archaeologists were investigating nearby, it would be better to take the jar there and ask the experts to examine it.

He brought the jar to the archaeologists and recounted how he had discovered it. After careful verification, the experts confirmed that it was the Hawk-Shaped Vessel from the Neolithic period.

The Hawk-Shaped Vessel has a simple appearance resembling a hawk, measuring 35.8 cm in height and 23.3 cm in diameter. Upon realizing that it was a valuable treasure, the old man was extremely surprised and immediately handed the Hawk-Shaped Vessel over to the archaeological team.

Thanks to this, the artifact became well-known, and it is currently stored and protected in the National Museum of China.

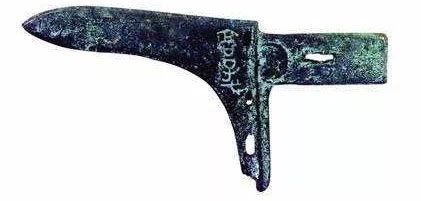

The Caozi Spear from the Spring and Autumn Period

The Caozi Spear is a weapon from the Spring and Autumn period, recognized as a first-class cultural treasure, currently housed in the Shandong Provincial Museum in China. This artifact was first discovered in 1970 when a rural boy found it among scrap metal and sold it for 5.97 yuan. After some time, it was lost and later recovered by the cultural and historical relics department. Sixteen years later, the boy who discovered the Caozi Spear had grown up. One day, he visited the museum and recognized that the scrap metal he had sold years ago had become a national treasure, now exhibited across the country. He shared with the museum staff the story of how he found the Caozi Spear as a child.