- Time Period: 1238-1527

- Location: Granada, Andalusia, Spain

The Kingdom of Granada, part of the Nasrid dynasty, was the last bastion of Al-Andalus, the Islamic rule over the Iberian Peninsula that developed on the western edge of the medieval Islamic world. Following the decisive Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa (1212), key cities of Al-Andalus fell to Christian forces: Córdoba, the former capital of the Muslim king, was captured in 1236 and Seville in 1248. Only the small Kingdom of Granada remained autonomous as its founder, Muhammad I (1232-72), declared himself a vassal of the King of Castile. The Kingdom of Granada endured until 1492 when it was conquered by the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile. Remarkably, this same year marked the discovery of the Americas, signifying the end of Spain’s Reconquista and the beginning of its colonization of the New World.

The Alhambra Palace viewed from the south (Photo: cs.cmu.edu)

A Testament to Islamic Culture

The greatest achievement of the Nasrid kings is undoubtedly the Alhambra Palace, which served to promote the culture, preferences, and refinement of Islamic civilization. This assertion is closely linked to Granada’s own awareness of its vulnerability, and perhaps for this reason, the Alhambra Palace is enveloped in a sense of nostalgia for a past that is neither celebrated nor romanticized. In fact, one of the most striking features is the use of poetry to decorate the rooms and spaces, with verses composed by famous court poets such as Ibn al-Yayyab, Ibn al-Jatib, and Ibn Zamrak.

The theme of reminiscing about the past is also evident in the architectural structure of the palace. Besides specific references to Islam, the palace incorporates many forms characteristic of ancient Greek and Roman architecture. Thus, the Alhambra Palace not only contains poetry but also embodies certain scholarly knowledge of classical Hellenistic traditions.

History of Construction

The Alhambra Palace is constructed on a hill overlooking the city of Granada.

|

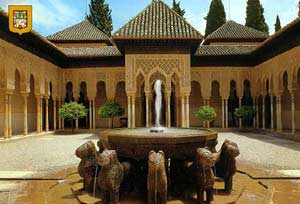

| The famous Lion fountain, viewed from one of the gate arches within the palace. Four water channels converge into a fountain at the center, supported by 12 lions (Photo: classics.nd.edu) |

The name of the palace comes from al-Qalat al Hamra, meaning “the red castle,” due to the color of the bricks and earth from which it was constructed. The complex is surrounded by a protective wall, separating the palace from the city. The oldest parts of the fortress date back to the 11th and 12th centuries, but it was Muhammad I who initiated the construction of a palace to serve as a residence at this location. Various historical sources indicate that in 1238, “the Muslim king came to the palace called Alhambra, surveyed, marked the foundations of the castle, and supervised the construction. The walls were completed before the end of the year. He also opened a canal to bring water from the river.”

During the 13th century, Alhambra was appropriately considered a military structure. The first Muslim king to wish to reside in this palace was Muhammad IV (1303 – 1309), but under King Yusuf I (1333 – 1354), the interiors of several towers in Alhambra were vibrantly decorated according to the king’s taste. This period saw the decoration of the Torre de Comares (Comares Tower) and Torre de la Cautiva (Tower of the Captive), where inscriptions by the poet Ibn al-Yayyab (1274 – 1349) can be found praising Yusuf I’s achievements.

The Alhambra Palace reached its zenith during the reign of Muhammad V, who ruled from 1354 to 1359 and again from 1362 to 1391, his reign marked by internal strife typical in Granada’s history. He constructed the Palacio de los Leones (Lion Palace), surrounding the courtyard of the same name, as well as the Patio de los Arrayanes (Courtyard of the Myrtles) and many other areas of the Palacio de Comares.

Design and Organization

Measurements:

- Patio de los Arrayanes: 36.6 x 23.4m

- Sala de Comares: 11.3 x 11.3 m

- Height: 18.22m

- Court of the Lions: 28.5 x 15.7m

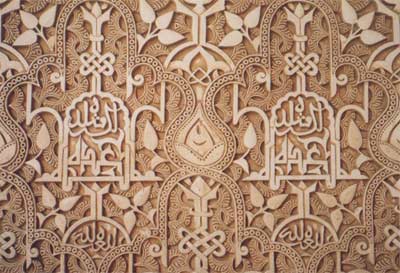

Decorative patterns on the walls carved into the rough plaster.

(Photo: home.cs.utwente.nl)

No direct documentation refers to the construction process, making it impossible to acquire any information about the architect responsible for the palaces in the Nasrid dynasty, the skilled craftsmen involved, or even the construction costs. The Alhambra Palace remains an anonymous masterpiece. There is also no precise information regarding daily life within the palace or even the original names of the rooms and halls. Due to the lack of detailed sources, the dating of various parts of the Alhambra Palace can only be confirmed through hypotheses and exterior assessments.

The construction of the palace complex primarily utilized bricks, along with concrete and mortar. Carved stone was used relatively sparingly, and granite was restricted mainly to paving and column work. Decorations covering walls, ceilings, and floors were primarily made of wood, ceramics, and rough plaster. A splendid example of the wood carving process is found in the ceiling of the Sala de Comares or Sala de Embajadores (Ambassadors’ Room).

|

| The Generalife Palace: A garden with a water channel in the middle and a fountain, featuring myrtle, citrus trees, cypress, roses, and other flowers (Photo: travelaboutinc) |

Colorful ceramic tiles fill many interior and exterior spaces, with geometric patterns reflecting a dazzling array of colors. However, the most striking feature of the Alhambra Palace is the rough plaster work, adorned with plant motifs and inscribed verses. This rough plaster technique is also used to create the stunning muqarnas ceilings in the Sala de las Dos Hermanas (Hall of the Two Sisters) and Sala de los Abencerrajes.

Within the walled complex of the Alhambra Palace are three distinct sections: the Alcazaba, located at the highest point, serving strict military purposes, the Medina, and the palace itself. At times, there were as many as seven palaces, but only two remain that best represent the Alhambra of the Nasrid dynasty: the Palacio de Comares and the Palacio de los Leones. The courtyards form a vital element of order, with water in the form of pools and fountains playing an important role.

The inner courtyard of the Palacio de Comares (Patio de los Arrayanes) is rectangular, intersected by a pool running from north to south. Much more complex and intricate is the Patio de los Leones, located within the palace of the same name. This courtyard is surrounded by a portico with a total of 124 granite columns, centered around the famous Lion Fountain. The cross-shaped structure is emphasized by water channels running through it and the arrangement of four rooms surrounding along the vertical and horizontal axes.

Near the Alhambra, but outside its walls, is the Generalife Palace, resembling a summer residence, built by the Muslim king Muhammad II (1272 – 1302), and renowned for its gardens, faithfully reflecting the most typical features of Islamic garden design.

Later History

|

| (Photo: nmhschool) |

For most of the 15th century, from the reign of Muhammad V until the Christian conquest, the Alhambra Palace largely retained its 14th-century appearance, with no significant changes. After 1492, Spanish rulers began a series of politically symbolic developments in Granada. Emperor Charles V even left his mark on the walls of the Alhambra Palace. His significant work was his palace, designed by architect Pedro Machuca in 1527: a classical structure with modest decoration and geometric layout (a circle within a square) symbolizing the deliberate contrast between Islamic and Christian styles. Although Charles V did not live in the palace, no additional constructions were made after his reign; only renovations and maintenance, as well as some destruction, took place.

It was the Romanticists, particularly British painters, who rediscovered the palace and drew Western attention to it in the 19th century, idealizing it and transforming it into a legendary place, steeped in exoticism and sensual pleasure. This image is reflected in the art of David Roberts and John Frederick Lewis, as well as in the evocative works of Chateaubriand, Théophile Gautier, and especially Washington Irving in his works “The Conquest of Granada” (1829) and “Tales of the Alhambra” (1832). A significant contribution to reviving Islamic art came from Owen Jones in his work Plans, Elevations, Sections and Details of the Alhambra (1842 – 1845). Since the 19th century, the Alhambra Palace has become a renowned tourist attraction. In 1984, both the Alhambra and Generalife were listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

The wonder of the Alhambra does not lie in its timelessness, grandeur, or richness, nor does it represent any unification of styles, having been built, destroyed, and rebuilt in different periods. Instead, the charm of the Alhambra primarily resides in its extraordinary decoration and, above all, in the balance and insightful understanding that nature and architecture together provide. Throughout the palace, water and vegetation play a harmonious and active role.