The Lunar New Year, known as Tết Nguyên Đán, is the largest festival among Vietnam’s traditional celebrations. It marks the transition from the old year to the new year, as well as the cyclical changes in nature and the world around us.

It seems that everyone knows that Tết Nguyên Đán is one of the most significant and important holidays in Vietnam, deeply imbued with unique cultural identity. But where does Tết Nguyên Đán actually originate, and what is the significance of its name?

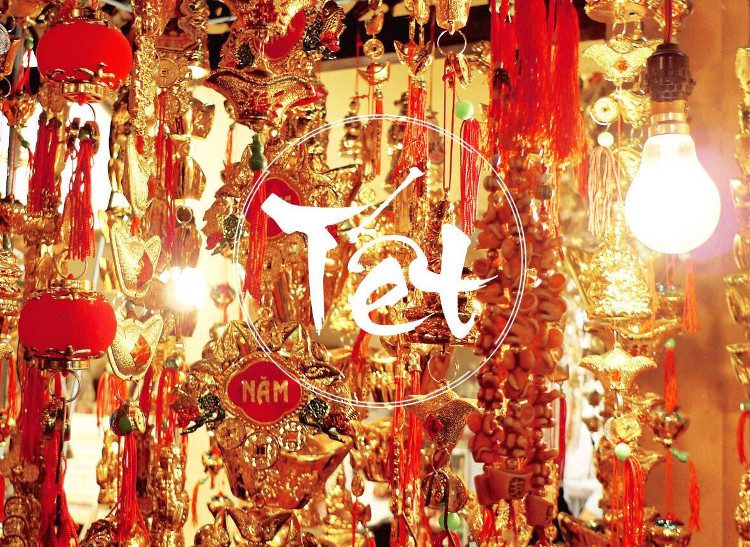

The arrival of Tết not only ignites the anticipation of countless children eager to wear new clothes, enjoy sweets, and receive lucky money, but it also carries profound meaning. It symbolizes the transition between the old year and the new year, the cyclical operations of nature, and the connection between life and the universe. Additionally, it reflects the desire for longevity, harmony among Heaven, Earth, and Humanity, and the bonds within the community, family, and clan. Tết Nguyên Đán also serves as an occasion to pay homage to one’s roots, embodying the spiritual and emotional values that have become cherished traditions for the Vietnamese people.

Tết Nguyên Đán is also referred to as Tết Cả, Tết Ta, Tết Âm Lịch, Tết Cổ Truyền, Tết năm mới, or simply Tết. The term “Tết” is derived from “tiết”. The two characters “Nguyên Đán” have Chinese origins; “nguyên” means beginning or initiation, while “đán” refers to early morning. Therefore, the correct pronunciation should be “Tiết Nguyên Đán”. Vietnamese people affectionately refer to Tết Nguyên Đán as “Tết Ta” to distinguish it from “Tết Tây” (the Western New Year).

Tết Nguyên Đán – also known as Tết Cả, Tết Ta, Tết Âm Lịch, Tết Cổ Truyền…

There are theories suggesting that Vietnamese culture, rooted in rice agriculture, divided the year into 24 distinct periods based on agricultural needs, each with its own transitional moment, with the most significant being the start of a new cultivation cycle—this is Tiết Nguyên Đán.

Later, due to the evolution of language, the character “tiết” was localized to “Tết,” leading to the name Tết Nguyên Đán as we know it today.

When is Tết Nguyên Đán Celebrated?

The Vietnamese lunar calendar differs from the Chinese lunar calendar, meaning that Tết Nguyên Đán in Vietnam does not completely coincide with the Chinese New Year or the New Year celebrations in other cultures influenced by Chinese traditions.

Because the lunar calendar is based on the moon’s cycles, Tết Nguyên Đán occurs later than the Gregorian New Year. Due to the rule of having a leap month every three years in the lunar calendar, the first day of Tết Nguyên Đán never falls before January 21 or after February 19 of the Gregorian calendar. It typically falls between late January and mid-February. The Tết festivities generally last about 7 to 8 days at the end of the old year and the first 7 days of the new year (from the 23rd day of the last lunar month to the end of the 7th day of the first lunar month).

Tết Nguyên Đán typically falls between late January and mid-February. (Photo: Nhat Tai).

Origins of Tết Nguyên Đán

Influenced heavily by Chinese culture during over a thousand years of Chinese domination, Tết Nguyên Đán is one of the cultural facets introduced during that time. According to Chinese history, the origin of Tết Nguyên Đán dates back to the era of the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors and has evolved through different dynasties. During the Xia Dynasty, the rulers preferred the color black and thus established the first month of the lunar calendar as the month of the Tiger. The Shang Dynasty favored white, choosing the twelfth month as the new year. The Zhou Dynasty preferred red, designating the eleventh month as the festival month. The aforementioned emperors had differing beliefs about the moments of “creation of heaven and earth.” For example, the hour of the Rat signifies heaven, the hour of the Ox signifies earth, and the hour of the Tiger signifies the birth of humanity, leading to various New Year celebrations.

During the Eastern Zhou Dynasty, Confucius standardized the New Year celebration to a specific month— the month of the Tiger. In the Qin Dynasty (3rd century BC), Emperor Qin Shi Huang shifted it to the month of the Pig, which is the tenth month. Later, during the Han Dynasty, Emperor Wu of Han (140 BC) reinstated the celebration to the month of the Tiger, or the first month. After that, no other dynasty changed the New Year month.

In the time of Dongfang Shuo, he believed that during the creation of heaven and earth, the rooster was born on the first day, the dog on the second day, the pig on the third day, the goat on the fourth day, the ox on the fifth day, the horse on the sixth day, and humanity on the seventh day, with grains being born on the eighth day. Thus, the New Year is traditionally counted from the first day to the end of the seventh day.

The New Year is traditionally counted from the first day to the end of the seventh day. (Image: internet).

Significance of Tết Nguyên Đán

Tết Nguyên Đán represents not only the emotional connection between heaven, earth, and humanity with the divine in Eastern beliefs, but more profoundly, it is a day of reunion for families. Each Tết, regardless of profession or location, everyone wishes to return to gather under the family roof for three days, to pay respects at the ancestral altar, visit ancestral homes, graves, wells, and courtyards, and relive cherished childhood memories. “Going home for Tết,” is not just a common concept of coming and going, but a pilgrimage to one’s roots, the place of origin.

Tết Nguyên Đán carries deep and sacred meanings, marking the farewell to the old year and the welcoming of the new year, wishing for better health, improved livelihoods, enduring personal and family happiness, starting from agricultural ideologies and gradually expanding into the social fabric, while still embodying beautiful humanitarian values.

Vietnamese people believe that Tết Nguyên Đán is an opportunity to express the principle of “Drinking water, remembering the source” in the most profound and tangible way. The value of honoring one’s roots is both a spiritual and emotional value for the Vietnamese during Tết Nguyên Đán. This value has become a lasting and esteemed traditional lifestyle.

It is believed that during Tết Nguyên Đán, ancestors are present at the ancestral altars, in family temples, to witness the sincerity of their descendants, and from there, bless them with health, stable livelihoods, and happiness within the bonds of love among grandparents, parents, children, and spouses. This is the spiritual significance of Tết Nguyên Đán.

A beautiful bonsai kumquat tree for Tết.

When lighting incense and preparing offerings for ancestors during Tết Nguyên Đán, the Vietnamese find satisfaction and peace in their lives as they enter the new year.

During Tết, Vietnamese people prepare every aspect of life to be abundant, ethical, and traditional. For instance, meals should be delicious and nutritious, distinctly different from regular days. Clothing should be beautiful, regardless of age or gender: men, women, farmers, workers, scholars, or officials, the elderly or the young.

Everyone feels a closer bond, speaking kindly with thoughtful language. For example, during Tết, it is customary to wish each other health and longevity, wishing for “a prosperous year, ten times better than last year.” Though it may sound extravagant, it is still melodious and heartfelt. Thus, during Tết, people are cheerful and gentle, an opportunity to reconcile any differences, “harboring anger until Tết ends.”

This embodies the moral and aesthetic values that the Vietnamese strive for and often achieve. Therefore, the days during Tết Nguyên Đán are truly joyful and happy days for everyone.