The execution of prisoners in ancient China at the time known as “Noon Three Ke” is a topic often depicted in films and literature. What exactly is this time during the day, and why was it regulated in this manner?

According to ancient Chinese timekeeping, “time” and “ke” are two units of measurement. A full day is divided into 12 time periods (each equivalent to 2 hours), further divided into 100 “ke” (marks on a small water bucket used to measure time; one bucket of water would drip out over a full day and night, with each “ke” representing 15 minutes).

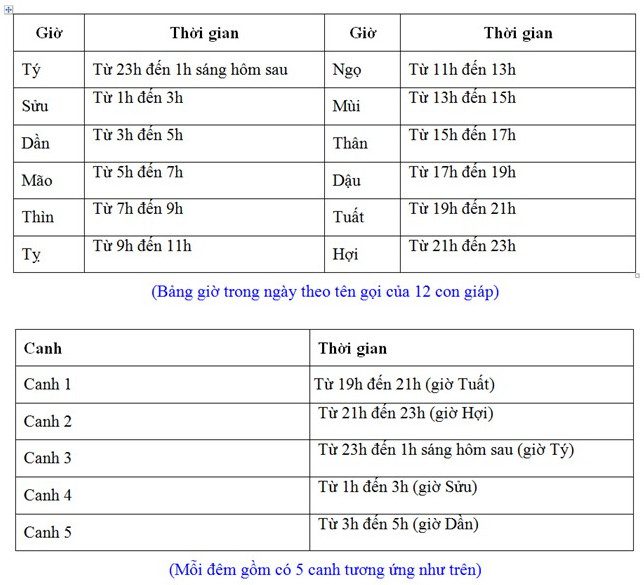

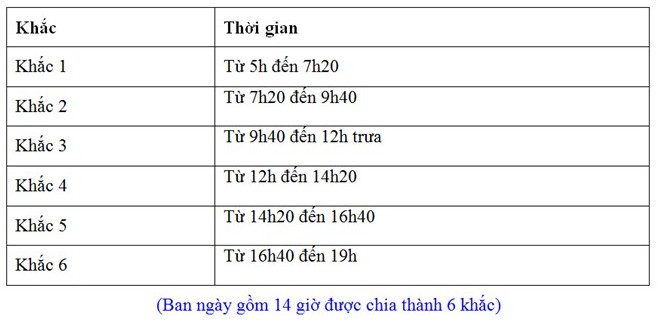

Time and “Ke” Calculation in Ancient Times

The time “Noon” corresponds to the hours between 11 AM and 1 PM. Noon Three Ke is approximately 12 PM, the moment when the sun is at its zenith and shadows on the ground are shortest. According to this calculation, Noon Three Ke corresponds to 11:45 AM.

Ancient Time and Ke Calculation.

Ancient Ke Calculation.

People in ancient times believed that this was the moment when yang energy was at its strongest.

Executing Prisoners at Noon Three Ke

According to the book “Gong Men Yao Lue,” ancient people were quite superstitious about executions. They believed that ending someone’s life constituted “yin affairs.” Regardless of whether the person deserved punishment or not, their soul could linger, following the judges, executioners, and those involved in the death sentence.

Therefore, executing a prisoner at Noon Three Ke – when yang energy is at its peak – was believed to suppress the lingering spirit of the prisoner. This is the primary reason why executions were scheduled for “Noon Three Ke.”

Additionally, according to ancient beliefs, another reason pertained directly to the prisoner. Noon Three Ke was also considered a time when human vitality is at its weakest, exhausted, and more prone to drowsiness. Executing during this time would result in less suffering for the prisoner. Choosing to execute at Noon Three Ke, from this perspective, could also be seen as a humane consideration for the prisoner.

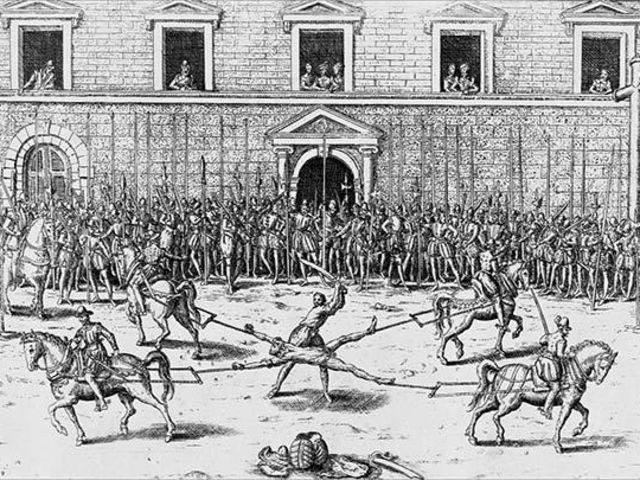

The Punishment of Five Horses Ripping the Body Apart.

Many Chinese novels that mention the execution of prisoners often place it within the context of autumn or winter. In fact, executing prisoners during these seasons stems from the ancient belief of “spring brings life, summer nurtures, autumn harvests, and winter stores.” Among the four seasons, autumn and winter are typically cold and dreary, reflecting a somber atmosphere that aligns with the “death decree” of heaven and earth. Thus, it is understandable that prisoners were executed during these seasons.

During the Tang and Song dynasties in China, legal codes stipulated that executions could not be carried out during significant lunar periods, including the time between the beginning of spring and the autumn equinox, as well as during the months of January, May, and September; on days of major ceremonies, days of fasting, days coinciding with the 24 solar terms, and certain days within the month (the first, eighth, fifteenth, eighteenth, twenty-third, twenty-fourth, twenty-eighth, twenty-ninth, and thirtieth) designated as “prohibited for executions.”

Moreover, executions were also prohibited during weather conditions such as “rain not yet ceased, and the sun not yet risen.” Due to these regulations, during the Tang and Song dynasties, there were less than 80 days each year suitable for carrying out death sentences.

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the legal procedures also regulated execution times similarly to those in the Tang and Song, but without specifying exact hours.

The book “Zheng Ming Hua” notes that: “Now it is late autumn and early winter. In the prisons of various prefectures, counties, and districts, those serious offenders categorized as ‘ten evils without mercy’ are being scheduled for execution. On that day, the county magistrate of Song Liu, Cao Jie, received the imperial edict and ordered several named prisoners to be taken to the street intersection for execution at the fifth watch.”

Thus, the time of execution was not at noon.