On June 12, scientists declared that international efforts to protect the ozone layer are a “great global success” after revealing that harmful gases in the atmosphere are decreasing faster than expected.

The Montreal Protocol, signed in 1987, aimed to phase out substances that deplete the ozone layer, primarily found in refrigeration equipment, air conditioners, and aerosol sprays.

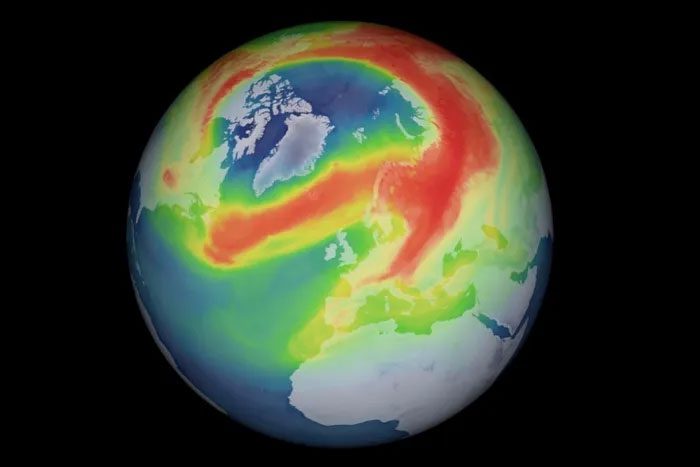

Newly discovered ozone hole in the Arctic. (Photo credit: BIRA/ESA)

A recent study found that levels of hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) in the atmosphere—the harmful gases that create holes in the ozone layer—peaked in 2021, five years earlier than predicted. Lead researcher Luke Western from the University of Bristol in the UK stated: “This is a great global success. We are seeing things heading in the right direction.”

The most harmful CFCs were eliminated by 2010 in efforts to protect the ozone layer—the shield that protects life on Earth from harmful ultraviolet rays from the sun. The HCFC chemicals that replaced them are expected to be completely phased out by 2040.

The aforementioned study, published in the journal Nature Climate Change, examined the concentrations of these pollutants in the atmosphere using data from the Advanced Global Atmospheric Experiment and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration of the United States.

Mr. Western attributed the significant decline of HCFCs to the effectiveness of the Montreal Protocol, along with stricter national regulations and the industry’s shift in anticipation of the upcoming ban on these pollutants. He remarked: “In terms of environmental policy, many are optimistic that these environmental agreements can work effectively if enacted and properly adhered to.”

Both CFCs and HCFCs are potent greenhouse gases, meaning their reduction also contributes to the fight against global warming. CFCs can remain in the atmosphere for hundreds of years, while HCFCs have a lifespan of about two decades, Mr. Western noted. Even when they are no longer produced, the use of these products in the past will continue to affect the ozone layer for many years to come.

The United Nations Environment Programme in 2023 estimated that it could take four decades for the ozone layer to recover to levels before the hole was first discovered in the 1980s.