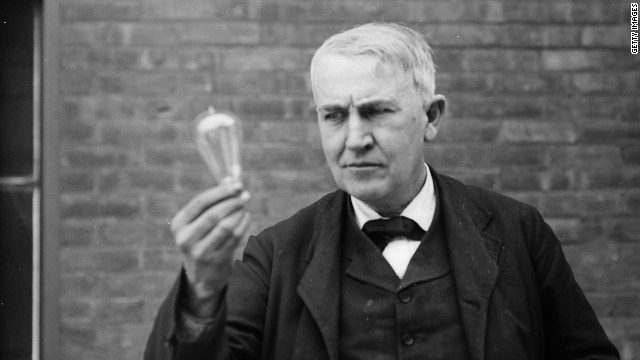

Thomas Edison was a scientist, inventor, and businessman who invented many devices that have significantly impacted our lives. Throughout his life, this great inventor held 1,093 patents in the United States as well as patents in France, England, and Germany.

The Life and Inventions of Thomas Edison

- Thomas Edison (1847 – 1931) the number one inventor of the United States and the world

- 1. Childhood

- 2. Apprenticeship

- 3. Young newspaper owner and telegraph operator

- The “one of a kind” proposal to his secretary

- 4. The period of success

- 5. Invention of the phonograph

- 6. Invention of the electric light

- 7. Edison Electric Light Company

- 8. Invention of the motion picture projector

- 9. Vote counting machine

- 10. Stencil pen

- 11. Final fame

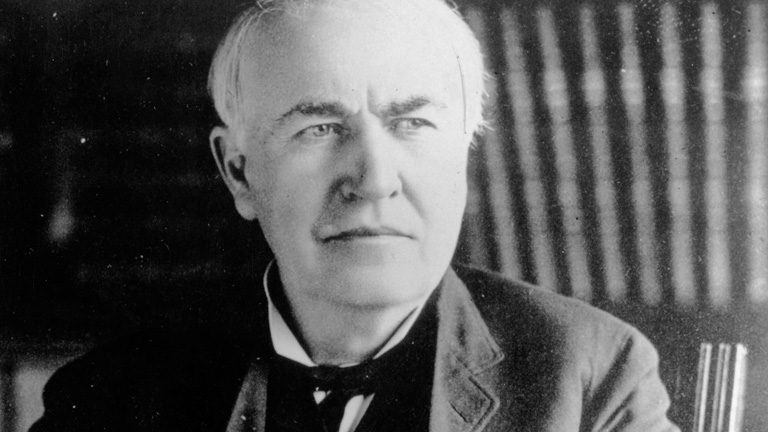

Thomas Edison (1847 – 1931).

Thomas Edison (1847 – 1931) the number one inventor of the United States and the world

1. Childhood

In December 1837, Captain William L. Mackenzie and his associates, including Samuel Edison, organized a revolution to seize the city of Toronto in Canada, but their efforts failed. To avoid capture, Samuel Edison fled to Michigan, USA, and settled in Detroit because, at that time, the Canadian government planned to exile political prisoners to Tasmania, Australia.

After successfully bringing his family, including his wife and two children, to the United States in early 1839, Samuel Edison moved to Milan, Ohio. Milan was a small town along the Huron River, a few miles from Lake Erie. In Milan, the trade was quite prosperous. From here, the locals transported grains, vegetables, firewood, and other agricultural products. Samuel Edison established a sawmill here, and business was thriving. It was in this new residence that the Edison family welcomed another child on February 11, 1847. Samuel named the child Thomas Alva Edison to honor Captain Alva Bradley, who had helped the Samuel family immigrate to the United States.

Alva, or Al for short, was a child with an unusually large head, which led doctors to predict that he would suffer from headaches. However, this prediction proved to be wrong, as Al’s brain later contributed significantly to the advancement of human technology.

Thomas Edison in his childhood.

As he grew older, Al became increasingly curious. He frequently asked questions like “why, how…” and his endless inquiries frustrated those around him, who often had to respond with “I don’t know.” At the age of five, Al often wandered by the river, watching adults work. There, he heard many songs and quickly memorized folk tunes, which demonstrated that Al had a very good memory, a skill that later allowed him to accumulate a vast amount of knowledge.

In 1850, railroads were established in many places across the United States. In Milan, the elders refused to allow the railroad to pass through their village, fearing it would disrupt river work. Consequently, the railroad was only established north of Ohio, leading to a decline in Milan’s prosperity. Samuel had to close the sawmill and moved the family to Port Huron, Michigan, in 1854. In Port Huron, Samuel traded grains, firewood, and also grew vegetables and fruits. At the age of eight, Al helped his father load fruits and vegetables onto a cart to sell door-to-door in the town.

Al was also enrolled by his parents in a unique school. The school had only one class with about 40 students of varying ages, all taught by a single teacher at different levels. The seats closest to the teacher were reserved for the less intelligent children. In class, Al asked many difficult questions but refused to answer the teacher’s questions. He often came last in class, which led his peers to mock him as foolish.

One day, during a visit from an inspector to the classroom, the teacher pointed to Al and said: “This child is crazy; he doesn’t deserve to be in school any longer.” Al was furious about being called “crazy” and recounted the incident to his mother. Upon hearing this, Nancy became angry and immediately took Al to school, stating to the teacher: “You say my son is crazy? Let me tell you, his mind is sharper than yours. I will keep him at home and teach him myself, as I am a teacher, so you can see what he will become in the future!”

From that day on, Alva no longer attended school and studied at home with his mother for six years. Thanks to her, Al gradually learned about the history of Greece, Rome, and World History. He also became familiar with the Bible, as well as the works of Shakespeare and other renowned writers, poets, and historians. However, most importantly, Al had a passion for Science. He could recount in detail the inventions, experiments, and biographies of great scientists such as Newton and Galileo. In just six years, Nancy imparted all her knowledge to him, from Geography with names of mountains and rivers to precise Mathematics. Nancy not only educated her son academically but also instilled virtues of honesty, integrity, confidence, and diligence, along with patriotism and love for humanity.

Al’s rapid progress in learning made his father very pleased. Samuel often gave his son small amounts of money to buy useful books, which allowed Al to immerse himself in works like Scott’s Ivanhoe, Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, and Dickens’ Oliver Twist. However, the author Al admired the most was Victor Hugo, and he often shared the stories he read with his friends.

At the age of ten, Al received a comprehensive science book by Richard Green Parker (School Compendium of Natural and Experimental Philosophy). In this book, Parker explained steam engines, telegraphs, lightning rods, Voltaic batteries, and more. The book answered many of Al’s previous questions and opened the door for him to the vast realm of Science, leading to his passion for Chemistry.

2. Apprenticeship

At the age of twelve, Al told his parents: “Dear parents, I need to earn some money now; please allow me to find a job.” His parents were concerned and tried to dissuade him, fearing he would face risks and that work would hinder his studies, but Al was determined; he insisted on trying to be independent and promised to be very careful.

At that time, the Grand Trunk Railway established a small station in Port Huron. Al obtained permission to sell newspapers, magazines, books, fruits, and candies on trains running the 101 kilometers between Port Huron and Detroit. From then on, the twelve-year-old boy woke up every month at 6 a.m. to catch the 7 a.m. train, arriving in Detroit at 10 a.m. Upon arriving, Al hurried to the library and spent hours poring over books he could not find in his hometown. He gradually developed a speed-reading ability and decided to start reading through the library’s 16,000 books, beginning with authors whose names started with A. By 6 p.m., Al would board the train again, returning to Port Huron at 9:30 p.m. He rarely went to bed before 11 p.m. because he spent over an hour conducting chemical experiments.

During his time selling newspapers and candies on the train, Al met many people, including telegraph operators, workers, and station staff. These individuals helped him in many difficult situations.

In 1861, the American Civil War broke out. The fiercer the battles became, the more newspapers sold. Al then thought of selling newspapers at all the minor stations. On April 1, 1862, the Free Press reported on the decisive battle at Shiloh in Tennessee. Al hurried to the Free Press office, the largest newspaper in Detroit, and ordered 1,000 copies to be paid for later. He and two friends then carried the newspapers onto the train. At the initial stations, sales were slow, but as they traveled further, demand increased, prompting Al to raise the price from 5 cents to 10 cents, and eventually to 25 cents per copy. By the end of the day, Al had sold all 1,000 newspapers before reaching Port Huron, earning over $100, the largest sum he had ever made.

3. The Young Newspaper Owner and the Telegraph Operator

Another initiative sprang to the mind of this determined boy: Al decided to start a newspaper. He quickly purchased a hand-operated printing press and established “a press office” in the luggage car. Al launched a small weekly newspaper called “The Weekly Herald.” This young editor realized he could not compete with the war news from the newspapers in Detroit, so he decided to focus solely on local events occurring along the railway line. He gathered news through local telegraph experts. Al served as the editor, manager, reporter, printer, and newsboy all at once. Thus, The Weekly Herald was a two-page publication, printed in three columns on each side. In addition to local news, Al also included announcements about births, deaths, accidents, and fires.

Al’s newspaper sold quite well. In its very first issue, around 400 copies were sold within a month. Al even accepted advertising in his paper. The Weekly Herald was once purchased by the British inventor Mr. Stephenson while he was traveling on a train through Port Huron. Mr. Stephenson praised Al’s ideas and affirmed that his newspaper was just as valuable as those produced by adults twice his age.

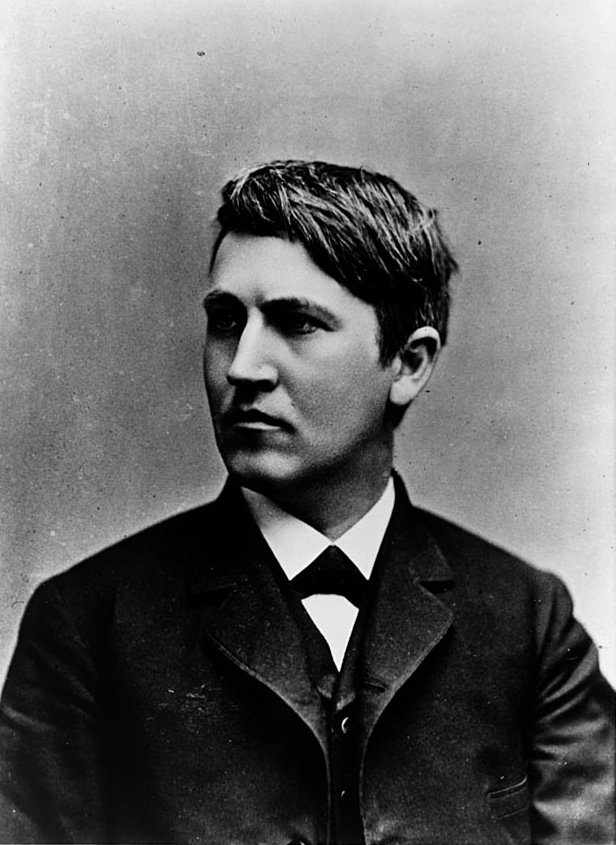

Thomas Edison was a strong, likable, and cheerful young man.

Thomas Edison was a strong, likable, and cheerful young man.

To increase readership, Al added a gossip column to the weekly, signing it under the pseudonym Paul Pry (Paul, the busybody). Al used his newspaper to criticize a few local individuals, carefully noting their names only by their initials. However, the short 101-mile distance did not protect Al from the wrath of those he mocked. One day, while Al was walking along the Saint Clair River, a burly man approached him, grabbed the young editor, and threw him into the river. Al surfaced soaked to the bone. Frustrated by being continually harassed by some readers, Al decided to stop publishing the newspaper.

One morning in August 1862, Al was talking to Mr. Mackenzie, a station agent and telegraph operator. Mr. Mackenzie had a two-and-a-half-year-old son named Jimmy, who often played around the station. While chatting, Al suddenly noticed Jimmy walking along the railroad tracks as a train car sped towards him. Realizing the immediate danger, Al rushed to the child, scooped him up, and rolled them both out of the way. In gratitude for saving his son, Mr. Mackenzie agreed to teach Al telegraphy and promised to help him find a job once he became proficient.

From that point on, Al dedicated 18 hours a day to learning about telegraphy and Morse code. Within a few weeks, Al had mastered all the signals sent by Mr. Mackenzie. After three months of learning, Al not only progressed to the point where Mr. Mackenzie called him a top telegraph operator, but he also invented a telegraph machine that was fully functional and allowed users to send messages quickly.

During the American Civil War, hundreds of telegraph operators were drafted into military service. As a result, commercial companies and railroads faced a shortage of operators. Therefore, finding a position as a telegraph operator was easy, and even a novice could secure a job. Around 1864, Al felt ready to take on a telegraph operator position, so he left his newspaper business and went to Stratford, Canada, to apply for a job in May. Al became a telegraph operator at the Stratford station, earning a monthly salary of $25.

From 1864 to 1868, Al worked in various places such as New Orleans, Indianapolis, Louisville, Memphis, and Cincinnati. During this time, the young man also decided to stop going by the nickname Al and instead used his full name, Thomas, or the more familiar Tom.

Thomas Edison was now a strong, likable, and cheerful young man. His openness and sincerity helped Tom make many friends, though his unique work habits led some of them to consider him eccentric. Tom dressed simply, wearing old, ink-stained clothes, and his worn-out shoes did not prompt him to think about buying a new pair. In the cold season, Tom preferred to endure the chill rather than spend money on a wool coat, as he had invested his money in scientific books and experimental equipment.

On the night of April 14, 1865, the American Civil War came to an end, resulting in hundreds of telegraph operators losing their jobs. Tom Edison returned to Louisville and, by the end of 1868, said goodbye to his parents to move to Boston to take up a telegraph operator position. At 21 years old, Tom made his first invention, a vote recorder. Tom submitted this idea to the Patent Office and presented it to Congress, but at that time, no congressman expressed interest in such a modern device. Despite this setback, Tom began working on many other projects. He managed to create a telegraph machine that could simultaneously send two messages over a single line.

A Unique Marriage Proposal to His Secretary

At 24, Edison became the owner of a well-known enterprise. As his life began to stabilize, this young man wanted to create a family. He became interested in a gentle, slender secretary named Mary Stilwell who worked in his company.

One day, Edison approached Mary and said: “Miss, I don’t want to waste time on pointless words. I have a very short and clear question: Will you marry me?”

The unexpected proposal left the secretary “stunned.” Seeing her reaction, Edison continued: “What do you think? Will you accept my proposal? Please think about it for five minutes.”

Regaining her composure, Mary Stilwell responded: “Five minutes? That’s too long! Yes, I accept.” On December 25, 1871, they married and had three children together.

However, in 1884, Mary passed away. At 39, Edison remarried Mina Miller, a girl 19 years his junior, and they also had three children together, including Charles Edison, who later became the Secretary of the Navy and Governor of New Jersey.

4. The Period of Success

One June morning in 1869, a ship departing from Boston slowly approached New York harbor. Edison, the 22-year-old young man, stood on the deck, gazing dreamily at the unfamiliar city, knowing no one and having not a penny to his name, as he was in debt for $800. Edison left Boston with empty hands after leaving all his experimental tools and books with his creditor, promising to return for them once he had enough money to pay off the debt. However, there were many things no one could take away from him: courage, determination to pursue his goals, education, technical experience, and other virtues he had acquired in his youth.

On his first day in New York, Tom visited all the telegraph offices looking for acquaintances and managed to borrow a dollar. Living on this meager amount for three days, Tom passed the Gold Indicator Exchange Company and noticed hundreds of people crowding and waiting. Approaching closer, he learned that the gold price ticker was broken, and as a result, the gold market was completely stalled. At that moment, the company’s director, Dr. Laws, was shouting, “I pay dozens of people, and none can do anything! Oh, I just need one talented worker!” Hearing this, Tom approached Mr. Laws and said, “Sir, I’m not your worker, but I believe I can fix the machine.” Within two hours, the machine Tom repaired was running smoothly again. The following day, after evaluating his capabilities, Dr. Laws hired Tom as the technical manager with a salary of $300 a month.

Despite the high salary, Tom Edison felt increasingly frustrated with the diligent work environment because his mind was brimming with dozens of dynamic ideas. While working at the exchange company, Edison met Franklin L. Pope, and the two discussed collaborating on a business venture. On October 1, 1869, Edison and Pope established an electrical and telegraph workshop, and shortly thereafter, J. N. Ashley from the Telegraph newspaper joined them. To stay close to his partner, Edison moved to the town of Elizabeth, New Jersey. To save time for essential tasks, Edison trained himself to take very short naps, sleeping three or four times a day. Besides the five hours he allocated for sleep, he used the rest of the time for technical improvements and professional work.

At that time, telegraph messages were recorded using dots and dashes printed on long strips of paper, which had to be manually transcribed before being sent to the recipients. If there were a way to print letters on telegraph forms, it would save a tremendous amount of invaluable time. This thought occupied Edison’s mind. Known for his technical prowess, General Marshall Lefferts, the director of the Gold and Stock Telegraph Company, asked Edison to transform the standard machine into a letter-printing telegraph machine. After months of research, Edison succeeded and received a patent in 1869. His new machine was simpler and more accurate than the old model, prompting Mr. Lefferts to propose purchasing the patent.

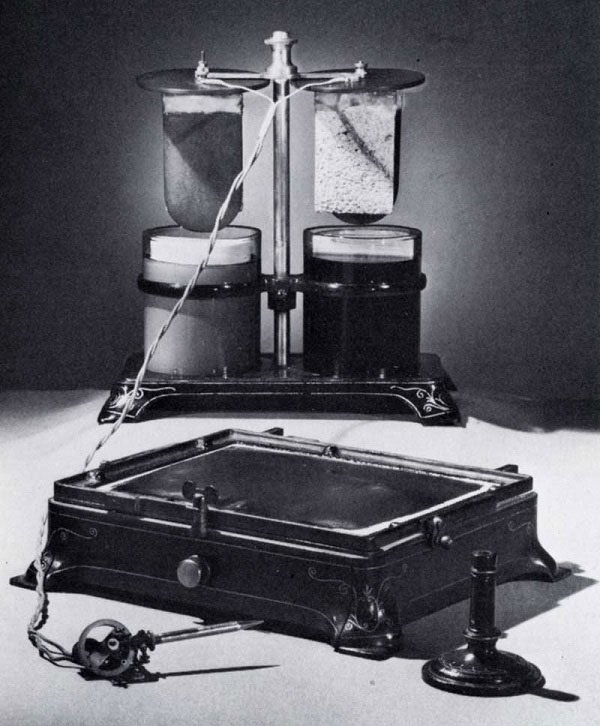

Telegraph Machine.

Telegraph Machine.

Edison’s business grew rapidly, prompting him and his colleagues to transform their old workshop into the Automatic Telegraph Company. Initially, he hired only 18 workers, but the workforce gradually increased to 50 and eventually reached 250. Many individuals who worked with Edison became skilled engineers and collaborated with him until their deaths. Edison organized the workers into teams, operating shifts both day and night. Despite being only 23 years old, he earned the nickname “the old man” due to his mature management of his team, which was sometimes a bit harsh; however, he compensated his employees generously based on their skills and working hours, as he wanted them to contribute with full professional integrity.

With a stout build, Thomas Edison had sharp eyes beneath thick lashes and a broad forehead. His heavy gait was noticeable as he moved back and forth in the workshop, his clothes often dirty and shabby, resembling a laborer more than a foreman, director, or a promising industrialist. Indeed, people were astonished by Edison’s workshop, not only due to its activities but also its hours. He hung six clocks in the shop, each showing different times, and his employees often worked until the job was done rather than stopping at a specific time. Between 1870 and 1876, starting at age 23, Thomas Edison patented 122 inventions, averaging more than one new idea each month.

During the period of his 46th invention, Thomas Edison heard about Christopher Sholes in Milwaukee experimenting with a machine called a “typewriter.” Recognizing that this new machine would significantly contribute to the development of the automatic telegraph, Edison invited Sholes to bring a sample to Newark and suggested several reasonable modifications. The Automatic Telegraph Company was the first to manufacture a typewriter, which was then used in the office, paving the way for the Remington typewriters that would later be used worldwide. While Morse invented the telegraph, Edison made many important improvements that even Morse himself would struggle to recognize in his own invention. Not only did Edison complete the duplex telegraph, allowing for the simultaneous transmission of two messages over the same line, but he also invented a method for transmitting four or five messages at once. Edison also saved the Western Union Company from bankruptcy with a new communication system.

One afternoon in 1870, Edison was alone in the office. The workers had gone home while the inventor remained behind to finish recording his observations on a machine he was completing. As he was about to leave, a heavy rain began to fall. Upon exiting, he encountered two young women taking shelter from the rain in the entryway. Edison introduced himself, saying, “I am Thomas Edison, the owner of this shop. Please come into the office to wait out the rain. I will go light the lamps.” One of the young women replied, “We wouldn’t want to trouble you, Mr. Edison. I am Mary Stilwell, and this is my sister Alice.” Edison bowed to the two young women and chatted with the Stilwell sisters to pass the time. However, Mary’s bright eyes, beautiful face, and graceful gestures captured Edison’s attention.

From that moment on, Edison could not forget Mary. He inquired among friends and learned that Mary was a teacher in Newark. Edison then sent a friend to visit the Stilwell family, and after the visit, he realized he had found the wife of his dreams. Following that, Edison often took Mary to the theater, attended concerts, or went camping outdoors. After a year of waiting for the Stilwell family’s approval, Edison married Mary on Christmas Day in 1871.

By the end of 1871, Edison had three different shops in Newark. The scattered workshops across a large city consumed much of the inventor’s time and precious energy. Therefore, Edison decided to find a location to build a larger workshop 40 miles outside Newark. Menlo Park was a small station in New Jersey, quiet and suitable for the inventor’s work. On January 3, 1876, construction began. Edison sketched out every detail for the laboratory and workshop plans.

In that same year, Western Union asked Edison to improve Alexander Graham Bell’s recently patented telephone. At the time, Bell’s phone was a complicated device, where the transmitter and receiver were combined, requiring users to speak into a mouthpiece and then place it next to their ear. The machine had limited range, and even speaking from one room to another, the static generated by the mechanism made conversation difficult. After two years of research, Edison invented the carbon microphone, completed a transmitter using carbon, and successfully transmitted voice over a distance of 225 miles. Edison greatly amplified the volume of the phone and made the sound clear. Western Union purchased the patent for the transmitter for $100,000. Edison’s success in improving the telephone led people to say, “Bell invented the telephone, but it was Edison who made it useful.”

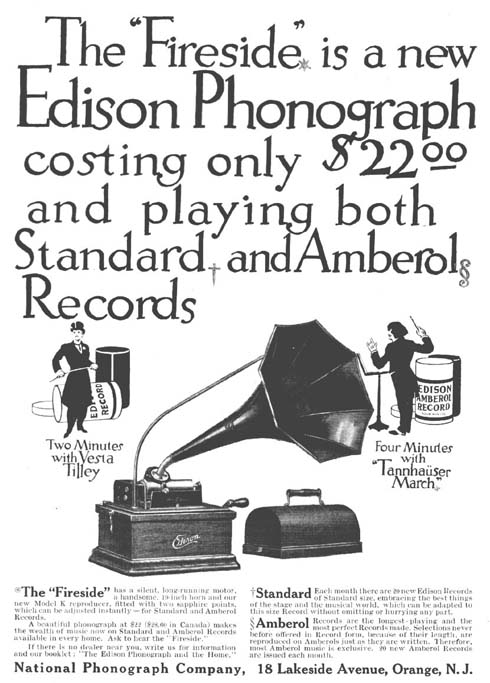

5. Invention of the Phonograph

At that time, Edison had a laboratory in Menlo Park, equipped with the resources for him to explore and research. Edison had a very distinctive working method. When an idea struck him, he would immediately experiment in numerous ways with the help of his assistants. Although the inventor had hundreds of patents by then, his fame truly became recognized by the public only after he produced the phonograph.

In reality, this invention stemmed more from his observational and reasoning abilities than from extensive searching. One summer afternoon in 1877, while Edison was fiddling with the automatic telegraph machine—composed of a steel stylus that etched grooves into a sheet of paper—he suddenly heard a sound when he spun the disc faster, noticing the sound varied with the disc’s roughness. This event fascinated the inventor. He repeated the experiment but this time, added a thin diaphragm to the stylus. Edison discovered that this component significantly amplified the sound.

His research into the telephone led Edison to realize that a thin metal diaphragm vibrated when speaking into a transmitter. Thus, it was possible to record these vibrations on a material and then make the diaphragm vibrate again, producing sounds akin to speech. That midnight, Edison sat in his office and sketched a design for the machine he envisioned. On December 24, 1877, Edison patented the phonograph, with the patent granted by the U.S. government on February 19, 1878.

Invention of the Phonograph by Thomas Edison.

Invention of the Phonograph by Thomas Edison.

A machine that could record and reproduce sound sparked public interest. To assure everyone that the phonograph could indeed speak, Edison decided to demonstrate the peculiar machine before the American Academy of Sciences. On the morning of April 8, 1878, Edison showcased the phonograph before Joseph Henry, President of the Smithsonian Institution, and in the afternoon, he performed at the Academy of Sciences. That evening, Edison received an invitation to present the phonograph to President Rutherford B. Hayes. The inventor impressed both the figures at the White House and the public alike. The world buzzed with excitement about this invention. Thomas Edison’s fame spread everywhere. The press wrote extensively about the 31-year-old inventor. One newspaper dubbed Edison the “Wizard of Menlo Park,” a title that gained popularity.

The phonograph was an invention that Edison cherished. He gradually improved the machine over many years, ultimately replacing the cylinder and crank with a rotating disc driven by a clock mechanism. Production of the phonograph increased significantly, reaching sales of $7 million by 1910. At 31 years old, Thomas Edison held 157 patents and was awaiting another 78 patents from Washington. Nevertheless, he continued to work tirelessly, putting in 18 to 20 hours each day.

6. Invention of the Electric Light

In March 1878, Edison began his research into electric light. At that time, the only known principle was that of the arc lamp, invented around 1809. When igniting an arc lamp, one had to constantly replace the carbon rods, and the lamp produced a crackling sound along with excessive heat and an unpleasant odor, making it unsuitable for indoor use.

In 1831, Michael Faraday discovered the principle of the dynamo, a machine that generates sparks to ignite gas within an oil engine. By 1860, a rudimentary electric lamp was created, which, although not practical, sparked interest in the potential of electricity for illumination. Thomas Edison believed that electricity could provide a softer, cheaper, and safer light compared to William Wallace’s arc lamp. Edison read extensively on electricity, aiming to deeply understand the theory to apply his knowledge practically. Today, among the 2,500 notebooks of 300 pages each preserved at the Edison Institute, over 200 contain notes on electricity. These notes formed the foundation for Edison’s great discoveries in the fields of Science and Engineering.

At that time, the press frequently reported on Edison’s research into electric lights, causing concern among gas lighting companies. Edison advised members of the Edison Electric Light Company to invest an additional $50,000 to continue his research. In the laboratory at Menlo Park, around 50 people worked tirelessly, surrounded by batteries, tools, chemicals, and machinery piled high in the research rooms. Alongside his electric light research, Edison had to improve many other machines and develop necessary techniques, as the electrical industry was still in its infancy. His work on electric lights also led to the invention of fuses, circuit breakers, dynamos, and wiring methods…

Based on Wallace’s arc lamp, Edison realized that light could be produced from a glowing material through heating. He experimented with many thin metal filaments, passing a strong current through them to make them glow, but they burned out quickly. In April 1879, Edison had a breakthrough idea; he wondered what would happen if a metal filament was placed in an airtight glass bulb. He called for Ludwig Boehm, a glassblower from Philadelphia, to come to Menlo Park and create the bulbs. The removal of air from the bulbs required a powerful pump, which was only available at Princeton University at the time. Eventually, Edison managed to bring that pump back to Menlo Park.

Edison tried inserting a very thin metal filament into the glass bulb and evacuated the air. When he connected the electricity, he achieved a brighter light that lasted longer, but it still wasn’t sufficient. On April 12, 1879, to protect his invention, Edison applied for a patent for the vacuum bulb, even though he knew that this type of lamp was not yet perfect, as he hadn’t found a suitable filament material. Edison experimented with platinum, but it was too expensive and consumed too much electricity compared to the useful light it produced. He tried various rare metals, such as rhodium, ruthenium, titanium, zirconium, and barium, but none yielded satisfactory results.

At 3 AM on Sunday, October 19, 1879, while Edison and his associate Batchelor were diligently experimenting, the inventor suddenly thought of using a very fine carbon filament. Edison immediately recalled the most common household item: sewing thread. He instructed Batchelor to burn the thread to obtain carbon fibers to place in the bulb. When the electricity was connected, the lamp lit up, emitting a steady and brilliant light. Edison and his associates breathed a sigh of relief. However, everyone was uncertain how long the light would last. Two hours passed, then three, four… up to twelve hours… and the light remained on. Edison had to ask his associates to take over so he could sleep. Thomas Edison’s first electric lamp burned continuously for over 40 hours, delighting everyone and restoring faith in the results. At that point, Edison increased the voltage, causing the filament to glow intensely before it eventually broke.

Thomas Edison and the invention of the electric lamp.

Thomas Edison and the invention of the electric lamp.

Proud of his invention, Edison wrote to the editor of the New York Herald, inviting them to send a correspondent to Menlo Park. Journalist Marshall Fox visited Edison’s laboratory and worked alongside the inventor for two weeks. On Sunday, December 21, 1879, the Herald reported on the invention of the electric lamp, but this report fueled public skepticism, with some claiming “such a light is contrary to the laws of nature.” Some reporters humorously suggested that “Edison’s electric lamp was launched into the sky like a balloon, becoming twinkling stars by evening.”

Edison found the denials amusing. He decided to publicly demonstrate the electric lamp to dispel all doubts. He strung hundreds of electric lights throughout the laboratory, his home, and along the streets of Menlo Park. On December 31, 1879, a special train traveled back and forth between New York and Menlo Park, carrying over 3,000 curious onlookers, including scientists, professors, government officials, and financiers, to witness the electric lamp firsthand. That night, the entire Menlo Park area was illuminated with the bright glow of this new lighting.

7. The Edison Electric Light Company

The success of the electric lamp led to a decline in gas companies, while Edison believed that electric lights would only be practical when he found a cheaper and more durable filament. He experimented with over 6,000 types of plant fibers, ultimately selecting a type of Japanese bamboo, which was used for ten years before being replaced by tungsten.

Edison then considered using electricity to illuminate a larger area. He decided to use a district in New York City covering 2,500 square meters as a testing ground. He developed various insulation methods and personally oversaw the installation of the wiring. By 1881, there were very few electrical specialists available. Edison opened a vocational school and appointed many of his former associates as instructors. He also authored a technical book on electricity. Thanks to this systematic approach, by the following year, Edison had over 1,500 workers digging trenches, laying cables, and connecting electricity to homes. Another crucial need arose: the establishment of a power plant. This required millions of dollars, leading to the founding of the Edison Electric Lighting Company of New York.

Edison established a factory for manufacturing electrical generator components, a workshop for producing electric bulbs, and a specialized facility for making electrical meters, lamp sockets, circuit breakers, and other necessary parts for this new industry.

Previously, the gas companies had a monopoly on street lighting and provided gas to the public. Edison aimed to replace those old lighting methods with a more convenient and cheaper alternative. He understood that he was undertaking a challenging venture; failure could cost him his reputation, finances, and the trust of the public and his peers. But Edison remained undeterred. He declared that the cost of electricity would be less than that of gas lighting, and he would only charge customers when they were satisfied with the electricity service. This large-scale experiment forced Edison to decline invitations to parties and speeches. It was common to see him, wearing a scarf around his neck, working in the trenches laying electrical cables or overseeing the construction of the power plant on Pearl Street.

On September 4, 1882, all design work was completed, ready for testing. At the Pearl Street power plant, workers fed coal into the furnace, and the engines began to operate. Edison lowered the lever, and in an instant, electricity traveled through 24 miles of wiring, lighting up hundreds of Edison bulbs in offices, factories, and homes. Thomas Edison had succeeded and regained the trust of the entire public.

Although he was a talented engineer, Edison despised profit-seeking and speculation. Once he achieved his research goals, he felt satisfied with the success and disregarded the profits his inventions would bring. Edison sold his bulb manufacturing plant to an electrical company, which later became very successful and renowned worldwide: General Electric.

Two years after the success of the electric lamp, Mary, his wife, fell ill with typhoid and passed away, leaving him with three children and a deep sense of loss. Overwhelmed with grief, Edison sent his children to live with their grandparents in New York while he sought solace in the laboratory. He realized the need for a larger workshop than Menlo Park. He chose the city of West Orange in New Jersey. Construction began, and during this time, Edison also established an additional laboratory for winter work, assembling a new facility in Fort Myers, a coastal area in Florida.

From 1881 to 1887, Thomas Edison engaged in extensive research and invented various types of machinery. He discovered a method to send telegrams from a station to a moving train. He experimented with preserving fruits in a vacuum, sketched designs for a helicopter, a cotton gin, an electric sewing machine, an electric elevator, an electric train, a snowplow, and even conducted studies on radio waves. Today, the “Edison phenomenon” is also applied to radio broadcasting lamps.

His busy work schedule helped Edison forget the sorrow of losing his first wife. He began to feel the need to step out of his ivory tower. People often saw him attending musical performances or present at social gatherings. One afternoon in 1885, at a dinner hosted by a friend, Edison encountered a beautiful and charming young woman sitting at the piano. Her name was Mina Miller, the daughter of Lewis Miller, an industrialist and inventor of the reaper. The two became close friends.

Meeting Mina alleviated Edison’s loneliness. Edison taught Mina Morse code because of his hearing difficulties. During a theater outing, he used Morse signals to inquire about Mina’s feelings for him, which she reciprocated. They married in 1886, when he was 39 and she was 21, but the age difference posed no barrier. Edison often dressed carelessly like a child, and Mina took care of him meticulously. She often hid his outer coat, so when he wanted to go out, he had to call for her, at which point she would control his attire, insisting he shave and comb his hair.

Mina also cared for Edison’s diet. She personally brought food to his laboratory and always encouraged him with gentle words. While Mary Stilwell, Edison’s first wife, played a significant role in his early successes, Mina Miller became his loyal companion and a valuable collaborator. She accompanied him on travels and to social events, reminding him of things he couldn’t hear clearly. At home receptions, Edison’s friends dubbed Mina “the most charming hostess in America.” Mina also created a happy family environment for Edison and their four sons and two daughters, including three children from Mary.

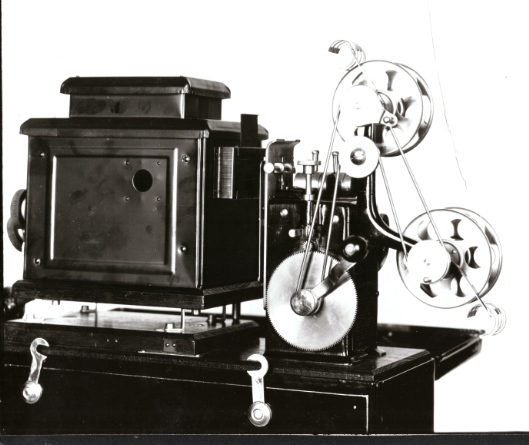

8. Invention of the Motion Picture Projector

One afternoon in 1887, Thomas Armat visited Edison and presented an early version of a projection machine. Armat knew that only Edison had the talent to transform that device into something practically useful. Upon seeing the kinematoscope (from the Greek word “kinema,” meaning movement), Edison immediately recognized its potential. He dedicated four years to improving the projector and developing the film camera, thus initiating a vast entertainment industry worldwide.

Edison invested $100,000 to set up a film studio in Bronx Park. He hired heavyweight boxing champion James J. Corbett to perform in Orange for filming. Edison produced numerous films and integrated phonographs into talking films.

Motion Picture Projector.

Motion Picture Projector.

As the film industry began to flourish, Edison turned his focus to new fields. He conducted many experiments with X-rays, which had recently been discovered by Roentgen. His research led to the invention of the fluoroscope and fluorescent lamp. Edison also patented the storage battery, developed a safe electric lamp for mines, improved computing machines, and discovered nickel-iron compounds, among many other minor inventions that are now considered commonplace but were groundbreaking at the time.

At age 60, Thomas Edison remained as industrious as ever. He “entertained himself by changing his work.” When asked about the art of “success,” he replied, “It is the ability to endure.” He defined, “Genius is 2 percent inspiration and 98 percent perspiration.” Edison believed that diligent mental work was the key to health and longevity, stating, “I only need my body to nourish my brain.”

When Edison turned 67, a fire destroyed seven uninsured buildings in West Orange, causing $5 million in damages. Edison smiled at his fate and immediately set to work rebuilding his old shop.

In 1915, the United States government planned to hold an exhibition in San Francisco called the Panama-Pacific Exposition to commemorate the completion of the Panama Canal. The organizers graciously designated October 21 as “Edison Day.” On the morning of October 21, 1915, the 36th birthday of the electric light bulb, Thomas Edison, along with Luther Burbank and Henry Ford, visited the Exhibition Hall. 50,000 people lined the streets to welcome the three figures who paved the way for Civilization. At the Assembly Hall, Edison received a special medal before thousands of admiring citizens, awarded for his commendable contributions to Humanity.

On June 28, 1914, World War I broke out and gradually involved the United States. Scientists and inventors answered their country’s call. Despite being nearly 70, Thomas Edison volunteered for the Navy and became the Chairman of the Technical Advisory Committee, hoping to bring glory to the United States. During this time, he invented a submarine detector, underwater searchlights, and methods for camouflaging warships. More than 40 of his tactical inventions earned him the Distinguished Service Medal, one of the highest honors of the United States Armed Forces.

9. The Voting Machine

This device was specifically invented for legislative bodies and election systems.

Edison was known for his intelligence and creativity, always seeking to contribute. Consequently, whenever he faced inconvenience, he would invent devices to overcome it. This is why, upon arriving in Boston in 1868, he began producing his inventions. The electronic voting machine was his first patent at the age of 22.

The device was specifically designed for legislative bodies and election systems, such as the United States Congress. It enabled faster recording of votes compared to the old system. It was a device directly connected to the desks of voters. At the desk, metal rods divided into two columns, “yes” and “no,” allowed lawmakers to move to indicate “yes” or “no,” and the information would be sent to the tallying station. After voting was completed, the counter would place a piece of chemical paper on top of the metal rods and roll a metal wheel over it. The results would appear on the paper, and the wheel would keep track of the total votes and compile the results.

Despite his efforts, when his product was presented to Congress, it was rejected because Congress did not want a device that consumed too much time and effort, leading to the machine being forgotten over time.

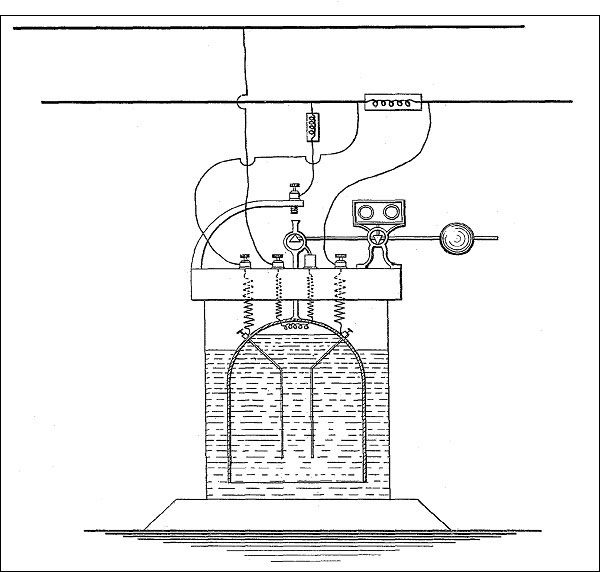

10. The Stencil Pen

Construction of the stencil pen.

In the 19th century, obtaining copies of contracts and documents consumed considerable time and effort across various professions. Because of this, Edison thought of creating a small electric motor device to aid in producing printing templates. He invented the precursor to the tattoo gun—the stencil pen. Edison was granted a patent for this machine in 1876. It used a tilted stick with a steel needle to puncture paper for printing purposes. Most importantly, it was one of the first effective devices for copying documents.

A company acquired this invention and mass-produced these “pens.” However, when sold on the market, the product faced complaints due to its heaviness and loud noise. Additionally, the costs for replacing batteries were quite high. Despite attempts to improve it, each modification made the pen worse, so he ultimately gave up on this troublesome invention and moved on to other projects. However, this abandoned product laid the groundwork for Samuel O’Reilly to create the first tattoo machine in 1891. Samuel received a patent based on Edison’s electric pen.

11. The Ultimate Fame

From the age of 12 until his old age, Thomas Edison worked tirelessly without knowing fatigue. He was self-taught from the age of 7 when his mother, Nancy, brought him home. Edison was an incessant reader and often juggled six projects at once. Even at 70 years old, he considered himself to be in his prime.

In 1918, when World War I ended, Edison returned to his laboratory and began researching a material essential for both wartime and peacetime: rubber. By the age of 75, he finally reduced his working hours to 16 hours a day. At 80, he produced long-playing records.

On October 21, 1929, Thomas Edison was invited as an honorary guest at a banquet in Detroit. That evening, U.S. President Herbert Hoover praised the great inventor. Edison responded with a few brief words of thanks. Suddenly, Mrs. Mina noticed that his face turned pale, and he slumped in his chair. The President’s personal physician treated him, but his strength could not be restored. From that moment, Edison gradually weakened.

From the age of 12 until his old age, Thomas Edison worked tirelessly without knowing fatigue.

From the age of 12 until his old age, Thomas Edison worked tirelessly without knowing fatigue.

On Sunday morning, October 18, 1931, Thomas Edison passed away, and three days later, on the 52nd anniversary of the first electric light bulb, his funeral was held with great ceremony in West Orange, New Jersey. That evening, all the lights across the United States were turned off for one minute to honor a great man, a “Friend of Mankind” who had given humanity a precious light 52 years earlier.

Two years earlier, in 1929, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the electric light bulb, Henry Ford established a historical village at Greenfield Park in Michigan to remind people of Thomas Edison’s life and work. The laboratory at Menlo Park was also rebuilt with all the old details and machinery. Henry Ford even sought out and acquired two copies of The Weekly Herald, the newspaper that over 70 years earlier, Thomas Edison had printed on a train. Not only Henry Ford respected Thomas Edison, but most of the great inventor’s collaborators admired him until his death.

Throughout his dedicated life, Thomas Edison held a total of 1,097 patents. He is a shining example of self-education. Besides the education his mother provided, Edison sought knowledge at public libraries. He reportedly read over 10,000 books by “sacrificing work hours to devour three books a day.” His exceptional memory and intelligence allowed him to understand and retain all the knowledge he collected until his death. In addition to his education in Science and History, Thomas Edison was also a scholar who specialized in researching Greek and Roman Civilization.

Phonograph | Motion Picture Projector | Edison Light Bulb |

Thomas Alva Edison’s dedication to humanity was realized in accordance with his saying: “My country is the world, and my religion is to do good.”