|

|

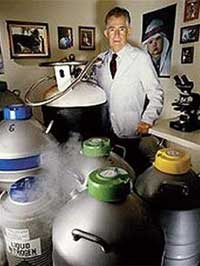

Robert K. Graham, the father of the “Genius Factory” plan – Photo: Slate |

During her lifetime, the renowned American ballet artist Isadora Duncan once spoke to British playwright Bernard Shaw about a child of theirs: “Imagine the combination of my body and your brain; we would give birth to a genius.” Bernard Shaw replied, “But what if, my dear, it has my legs and your brain?” This story has resurfaced in the media as they look back 20 years to explore a “Genius Factory” plan.

American journalist David Plotz recently investigated and shed light on the developments of an ambitious plan in the 20th century in an article published in Slate in mid-February.

This plan is associated with Southern California scientist Robert K. Graham, an optician who made $100 million from inventing unbreakable plastic lenses. Graham held racist views and idolized human genetics. He believed that the only way to preserve and enhance the human race was through a sperm bank of the era’s geniuses.

By artificially inseminating the sperm of elite individuals, it was thought possible to create a generation of super geniuses. With this intention, Graham invested the entire $100 million into the bold plan called “The Selective Seed Bank,” which specialized in storing sperm from Nobel Prize winners (commonly referred to as the “Genius Factory”).

On February 28, 1989, an article appeared in the Los Angeles Times titled: “All Nobel Laureates Will Be Volunteer Sperm Donors: A Plan to Enhance Human Genetic Potential.”

Along with calling for Nobel laureates to donate sperm, Graham organized advertisements in Mensa magazine seeking mothers. These women were educated, financially secure, but had husbands suffering from infertility. After compiling a list of “mother candidates,” Graham sent recommendation letters about the husbands, such as: “Mr. Fuschia, an Olympic gold medalist,” or: “Mr. Grey-White, a university professor.”

According to journalist David Plotz, Graham’s plan required absolute anonymity or the use of pseudonyms, so it was impossible to know specifically who the father of the child was. To ensure privacy, the identities of the mothers were also agreed to be kept confidential.

However, the public revelation of Graham’s plan led to severe criticism. Nevertheless, the “super children” began to be born. The first child was reported by the National Enquirer in 1982, and thereafter they continued to emerge.

By the time Graham passed away at the age of 90 in 1997, his reserve claimed to have “produced” 229 children across the United States and a few other countries. Later, Graham confessed that none of these children were actually the offspring of Nobel Prize winners.

The reason: the announced Nobel laureates were too old, so Graham ultimately used sperm from several younger scientists who donated! Only three Nobel laureates were known to possibly have donated sperm: the renowned mathematician John Forbes Nash, Jonas Salk – the creator of the polio vaccine, and semiconductor inventor William Shockley.

Two years after Graham’s death, his bank closed in 1999. The “super children” grew up without much public awareness, except for one case: Doron Blake. Blake had a remarkably high IQ of 180. By the age of two, Blake was using a computer, and by five, he could read Hamlet.

In 2001, Plotz found Blake, who was studying at Reed College. According to Plotz’s description, Blake was now a long-haired hippie with a nonchalant attitude. However, Blake had just dropped out of school and was immersed in researching spiritualism.

Blake sadly stated: “The Genius Factory, that is a bizarre idea. People hope I will achieve great accomplishments. But no. I can’t do anything special. If I had an IQ of 100 instead of 180, I would still be doing what I am doing now.”

TRẦN ĐỨC THÀNH